One of the critical aspects of exoplanet habitability is the long-term stability of the stars they orbit. Some stars are extremely massive and blast through their hydrogen fuel in only a few million years.

Rigel, the blue supergiant in Orion,…

One of the critical aspects of exoplanet habitability is the long-term stability of the stars they orbit. Some stars are extremely massive and blast through their hydrogen fuel in only a few million years.

Rigel, the blue supergiant in Orion,…

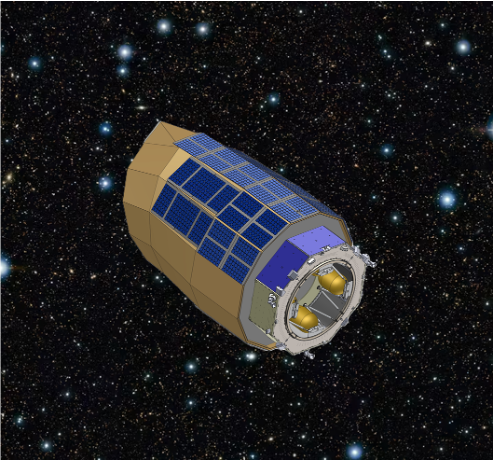

Lazuli will be the largest privately funded space telescope ever built — larger than the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: Schmidt Sciences

On Wednesday, Schmidt Sciences — an organization…

Photography by DWU Athletics

MITCHELL, S.D. — No. 10 Dakota Wesleyan Women’s Basketball hosted the Doane Tigers at the World’s Only Corn Palace in the team’s first home contest of 2026.

Both teams were able to…

President Donald Trump has called for US defence spending to be increased to $1.5tn (£1.1tn) in 2027 for what he called “these very troubled and dangerous times”.

That would be more than 50% higher than this year’s $901bn budget, which was…