Newswise — COLUMBUS, Ohio – A review of more than 1,000 studies suggests that using technology to communicate with others is better than nothing – but still not as good as face-to-face interactions.

Researchers…

Newswise — COLUMBUS, Ohio – A review of more than 1,000 studies suggests that using technology to communicate with others is better than nothing – but still not as good as face-to-face interactions.

Researchers…

London – UK – Wednesday 07 January – The Pokémon Company International and the Natural History Museum, London have unveiled new details about the highly anticipated pop-up shop first announced in September 2025, including a commemorative…

Sri Lanka have set a target of 129 runs for Pakistan in the first T20.

Pakistan won the toss and opted to field, giving the hosts a chance to bat. Sri Lanka managed 128 runs in 19.2 overs before being bowled out….

GPU Lease Financing to Support xAI’s Second Data Center

NEW YORK, Jan. 07, 2026 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) — Apollo (NYSE: APO) today announced that Apollo-managed funds and affiliates (the “Apollo Funds”) have led a $3.5 billion capital solution for Valor Compute Infrastructure L.P. (“VCI”), a fund managed by Valor Equity Partners (“Valor”), to support its $5.4 billion acquisition and lease of data center compute infrastructure, including NVIDIA GB200 GPUs, to a subsidiary of xAI Corp (“xAI”). The financing uses a triple net lease structure and will support one of the world’s most powerful compute clusters for ongoing model training and development of Grok.

NVIDIA invested in VCI as an anchor Limited Partner alongside many of Valor’s institutional investors. Since inception in 2023, xAI has rapidly established its position as one of the leading companies in artificial intelligence, with Grok 4 demonstrating strong performance across benchmarks.

“This transaction represents a hallmark, downside-protected investment for Apollo in the AI infrastructure space and underscores our role as a leading provider of flexible, asset-based capital for next-generation assets,” said Apollo Partner Christopher Lahoud. “We are supporting the growth of this transformative technology by investing in the critical infrastructure that enables it, alongside highly regarded partners like Valor and NVIDIA, who are driving the next wave of innovation.”

“VCI is an extension of our continued service as a firm to xAI. The fund provides investors with the opportunity to invest in critical artificial intelligence compute infrastructure with quarterly cash distributions and upside through ownership of the compute assets,” said Valor Founder, CEO and CIO Antonio Gracias.

Apollo estimates that global data center infrastructure will require several trillion dollars of investment over the next decade, driven by secular trends associated with the Global Industrial Renaissance and accelerating demand for compute capacity and AI workloads. Since 2022, Apollo-managed funds and affiliates have deployed over $40 billioni into next-generation infrastructure, including compute capacity, digital platforms and renewable energy.

Latham & Watkins LLP served as legal counsel to the Apollo Funds, Proskauer Rose LLP served as legal counsel to VCI and Sullivan & Cromwell LLP served as legal counsel to xAI.

About Apollo

Apollo is a high-growth, global alternative asset manager. In our asset management business, we seek to provide our clients excess return at every point along the risk-reward spectrum from investment grade credit to private equity. For more than three decades, our investing expertise across our fully integrated platform has served the financial return needs of our clients and provided businesses with innovative capital solutions for growth. Through Athene, our retirement services business, we specialize in helping clients achieve financial security by providing a suite of retirement savings products and acting as a solutions provider to institutions. Our patient, creative, and knowledgeable approach to investing aligns our clients, businesses we invest in, our employees, and the communities we impact, to expand opportunity and achieve positive outcomes. As of September 30, 2025, Apollo had approximately $908 billion of assets under management. To learn more, please visit www.apollo.com.

About Valor Equity Partners

Valor Equity Partners is an operational growth investment firm focused on investing in high-growth companies across various stages of development. For decades, Valor has served its companies with unique expertise to solve the challenges of growth and scale. Valor partners with leading companies and entrepreneurs who are committed to the highest standards of excellence and the courage to transform their industries. As of December 31, 2025, Valor had approximately $55 billion of assets under management. For more information on Valor Equity Partners, please visit www.valorep.com.

Contacts

Noah Gunn

Global Head of Investor Relations

(212) 822-0540

IR@apollo.com

Joanna Rose

Global Head of Corporate Communications

(212) 822-0491

Communications@apollo.com

________________________________

i Includes certain transactions that have signed but not yet closed. There can be no assurance that these transactions will close as expected or at all.

Taylor & Francis has announced an expansion in the scope of multidisciplinary journal PeerJ, aiming to offer authors a more streamlined publishing experience, enhanced visibility of their work and new…

PHOENIX — NASA is ramping up work on one large space telescope while also laying the groundwork for future observatories.

The agency announced Jan. 5 that it awarded three-year, fixed-price contracts to seven companies to study…

Kenny Lipscomb, a recycling vehicle driver and sanitation worker with the Facilities Management Roads and Grounds crew, has been selected to be featured for the January Staff Council Classified Staff Showcase.

Originally from…

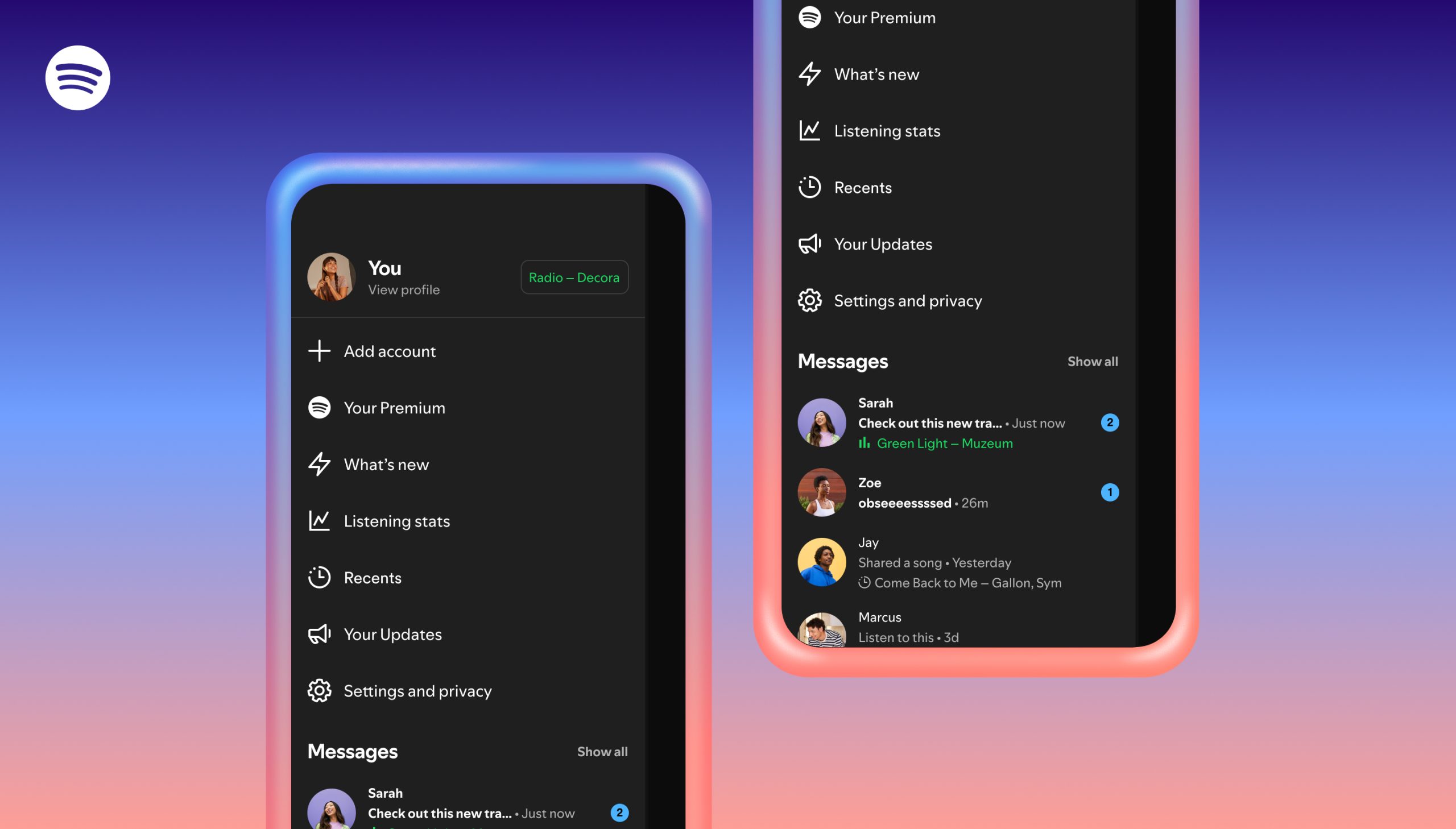

We know people use Spotify not just to listen, but to share the songs, podcasts, and audiobooks they love with their friends and family. When we launched Messages last year, we gave…

NORTH CHICAGO, Ill., Jan. 7, 2026 /PRNewswire/ — AbbVie (NYSE: ABBV) will announce its full-year and fourth-quarter 2025 financial results on Wednesday, February 4, 2026, before the market opens. AbbVie will host a live webcast of the earnings conference call at 8 a.m. Central time. It will be accessible through AbbVie’s Investor Relations website at investors.abbvie.com. An archived edition of the session will be available later that day.

About AbbVie

AbbVie’s mission is to discover and deliver innovative medicines and solutions that solve serious health issues today and address the medical challenges of tomorrow. We strive to have a remarkable impact on people’s lives across several key therapeutic areas – immunology, oncology, neuroscience, and eye care – and products and services in our Allergan Aesthetics portfolio. For more information about AbbVie, please visit us at www.abbvie.com. Follow @abbvie on LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube.

SOURCE AbbVie

Storage room 3495 at his University of Utah computing lab had gotten so packed full of cardboard boxes, Aleks Maricq jokes it had become hard to even see the floor.

It rivaled a game of Jenga — or maybe Tetris — as the research associate took…