Author: admin

-

Great-West Lifeco announces Normal Course Issuer Bid

Winnipeg, MB January 2, 2026 — Great-West Lifeco Inc. (“Lifeco”) announced today that it has received approval from the Toronto Stock Exchange (“TSX”) to renew its Normal Course Issuer Bid (“NCIB”).

Under the renewed NCIB, Lifeco may purchase for cancellation up to 20,000,000 common shares (“Shares”), representing approximately 2.2% of its 907,158,831 issued and outstanding Shares on December 23, 2025. The NCIB will commence on January 6, 2026 and continue until the earlier of January 5, 2027 and the date Lifeco completes its purchases pursuant to the notice of intention filed with the TSX. Based on the average daily trading volume on the TSX of 1,989,988 for the six months preceding November 30, 2025 (net of repurchases by Lifeco during that period), daily purchases will be limited to 497,497 Shares, other than block purchase exceptions. Purchases under the NCIB will be made at prevailing market prices through the facilities of the TSX, other designated exchanges and/or other alternative Canadian trading systems or by other means permitted by applicable law. Any Shares purchased by Lifeco pursuant to the NCIB will be cancelled. The actual number of Shares which may be purchased and the timing of any purchases will be determined by Lifeco management, subject to TSX rules and applicable law.

Lifeco’s Board of Directors (the “Board”) has authorized the renewed NCIB because, in the Board’s opinion, such purchases constitute an appropriate use of funds which will benefit both Lifeco and its shareholders. Lifeco will use the renewed NCIB to mitigate the dilutive effect of issuing securities under Lifeco’s Stock Option Plan and for other capital management purposes.

Under its prior NCIB (as amended on September 5, 2025), Lifeco received approval from the TSX to purchase up to 40,000,000 Shares from January 6, 2025 to January 5, 2026. As of December 23, 2025, Lifeco purchased 28,091,279 Shares at the weighted average price of $57.01 under its prior NCIB, including 12,443,866 Shares purchased from PFC (as defined below). As of December 23, 2025, a non-independent trustee purchased 75,457 Shares which were required to be counted against the NCIB limits in accordance with the TSX Company Manual, with no impact on the number of Shares outstanding. Those Shares were bought at the weighted average price of $53.45.

Automatic Purchase Plan

Lifeco also announced that it intends to enter into an automatic purchase plan (“APP”) with a designated broker to facilitate repurchases under the NCIB, including at times when Lifeco would ordinarily not be permitted to make purchases due to regulatory restrictions or self-imposed blackout periods. Purchases will be made by Lifeco’s broker at its sole discretion based on pre-set parameters in accordance with TSX rules, applicable law and the parties’ agreement. Purchases under the APP will be included in determining the total number of Shares purchased under the NCIB.

Purchases from Power

In addition, the TSX has granted an exemption that will permit Lifeco to purchase its Shares from Power Financial Corporation and its wholly-owned subsidiaries (collectively, “PFC”) in connection with the NCIB, in order for PFC to approximately maintain its proportionate percentage ownership (unadjusted for Share issuances pursuant to Lifeco’s stock option plan and other long-term incentive plans). PFC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Power Corporation of Canada and is the majority shareholder of Lifeco, holding approximately 68.677% of the issued and outstanding Shares (which does not include the approximately 2.44% of Shares held by IGM Financial Inc.). Purchases from PFC will be made during the TSX’s Special Trading Session pursuant to an automatic disposition plan agreement expected to be entered into between Lifeco, Lifeco’s broker and Power Financial Corporation and certain of its wholly-owned subsidiaries. Purchases from PFC will be made on any trading day that Lifeco makes a purchase from other shareholders pursuant to the NCIB. In the event that PFC does not sell Shares on any trading day as required (other than as a result of a market disruption event), the TSX exemption will cease to apply and Lifeco will not be permitted to make any further purchases from PFC pursuant to the NCIB. The maximum number of Shares that may be purchased pursuant to the NCIB will be reduced by the number of Shares purchased from PFC.

About Great-West Lifeco Inc.

Great-West Lifeco is a financial services holding company focused on building stronger, more inclusive and financially secure futures. We operate in Canada, the United States and Europe under the brands Canada Life, Empower and Irish Life. Together we provide wealth, retirement, group benefits and insurance and risk solutions to our over 40 million customer relationships. As of September 30, 2025, Great-West Lifeco’s total client assets exceeded $3.3 trillion.

Great-West Lifeco trades on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) under the ticker symbol GWO and is a member of the Power Corporation group of companies. To learn more, visit greatwestlifeco.comOpens in a new windowOpens in a new window.

For more information:

Media Relations

Tim Oracheski

204-946-8961

media.relations@canadalife.comInvestor Relations

Shubha Khan

416-552-5951

shubha.khan@canadalife.comRecent news

Great-West Lifeco reports results of conversion election for Non-Cumulative 5-Year Rate Reset First Preferred Shares, Series N

Great-West Lifeco announces dividend rates on Non-Cumulative 5-Year Rate Reset First Preferred Shares, Series N and Non-Cumulative Floating Rate First Preferred Shares, Series O

Great-West Lifeco announces conversion right of Non-Cumulative 5-Year Rate Reset First Preferred Shares, Series N

Continue Reading

-

Northern Lights: Geomagnetic Storms May Bring Aurora Borealis To 17 States Tonight – Forbes

- Northern Lights: Geomagnetic Storms May Bring Aurora Borealis To 17 States Tonight Forbes

- Map Shows States Where You Can See Northern Lights Tonight Newsweek

- A New Year’s toast: Here’s northern lights in your eye The Lewiston Tribune

- Aurora…

Continue Reading

-

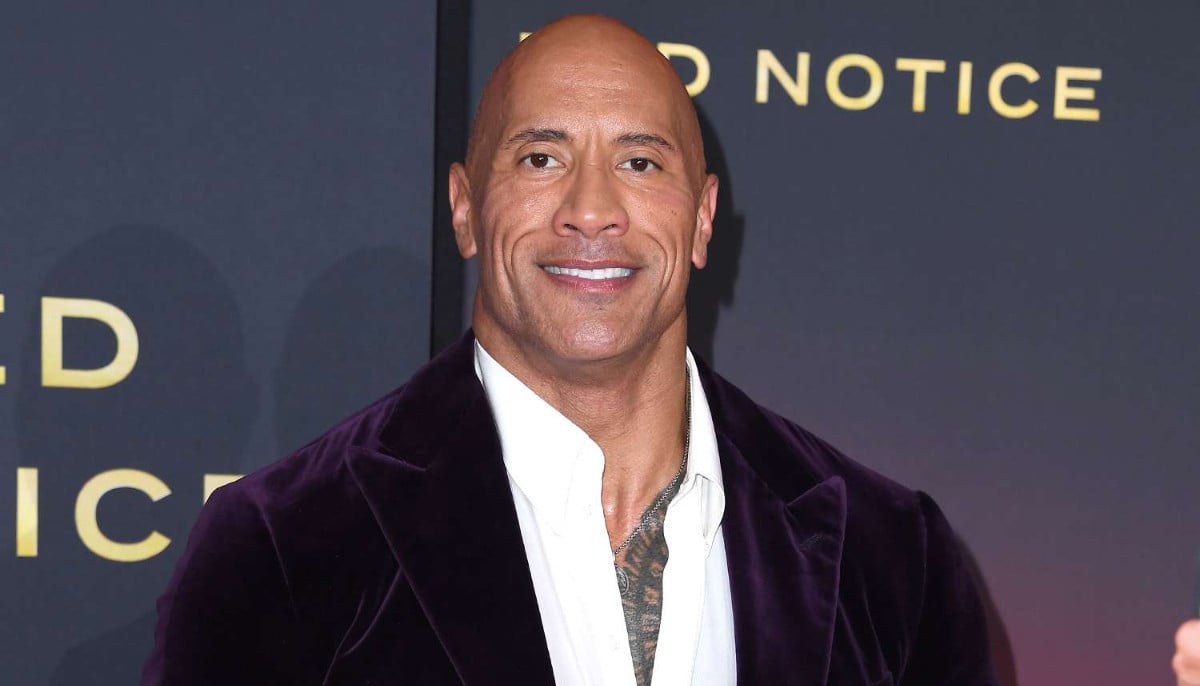

Dwayne Johnson reflects on ‘frustrating’ years in acting career

Dwayne Johnson is refelcting on transition from wrestling to acting, and how the latter…

Continue Reading

-

Pakistan, KSA discuss cooperation in energy sector – RADIO PAKISTAN

- Pakistan, KSA discuss cooperation in energy sector RADIO PAKISTAN

- Pakistan to participate in FMF at Riyadh Business Recorder

- ‘Mineral marvel’ to be showcased at Riyadh forum The Express Tribune

- Federal Minister for Petroleum Ali Pervaiz Malik…

Continue Reading

-

AJK’s upper reaches lashes with continual heavy rain, snowfall 2nd successive day

– Advertisement –

MIRPUR (AJK), Jan 2 (APP):Heavy rains and snow fall on upper reaches of Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) including Neeland Leepa vallies continued the 2nd consecutive day on Thursday.

The inclement weather led to a deep dip in…

Continue Reading

-

Bank First Corporation Announces Completion of Centre 1 Bancorp, Inc. Acquisition

MANITOWOC, Wis., Jan. 2, 2026 /PRNewswire/ — Bank First Corporation (Nasdaq: BFC) (“Bank First”) today announced it has completed its acquisition of Centre 1 Bancorp, Inc. (“Centre”), parent company of The First National Bank and Trust Company (“First National Bank and Trust”).

The closing marks an important milestone in bringing together two relationship-driven organizations. Effective immediately, Bank First is expanding its services to include trust and wealth management, integrating a skilled team from First National Bank and Trust. Customers now have access to a comprehensive suite of wealth planning, trust administration, and investment management services, provided by a team of professionals with deep expertise and a strong commitment to delivering personalized solutions.

First National Bank and Trust will continue to operate as a division of Bank First until the planned system conversion in May 2026. At that time, all locations will transition to the unified Bank First brand and digital banking platform. Throughout this process, customers will continue to work with familiar local teams, ensuring personalized service and a smooth transition as we move forward together.

The combined organization will operate 38 branch locations across Wisconsin and the Stateline area of Illinois, with approximately $6 billion in assets, strengthening its ability to serve individuals, businesses, and communities throughout the region.

Mike Molepske, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Bank First, stated, “This partnership brings together two long-standing, community-focused institutions committed to responsive, relationship-based banking. Together, we strengthen our ability to serve customers across Wisconsin and the Stateline area of Illinois with greater capabilities and expanded services.”

Following the closing, Steve Eldred, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Centre, will join the Board of Directors of Bank First and its banking subsidiary, Bank First, N.A.

Piper Sandler & Co. served as financial advisor to Bank First, and Alston & Bird LLP served as legal counsel. Hovde Group, LLC served as financial advisor to Centre, and Barack Ferrazzano Kirschbaum & Nagelberg LLP served as legal counsel.

Contact:

Bank First: Mike Molepske, Chairman & CEO, [email protected], (920) 652-3202SOURCE Bank First Corporation

Continue Reading

-

More Americans Plan Mental Health Resolutions Heading Into 2026

Washington, D.C. — Heading into 2026, more than one in three Americans (38%) say they plan to make a mental health-related New Year’s resolution, according to new findings from the American Psychiatric Association’s Healthy Minds Poll. This is up 5% from last year. Younger adults are leading this trend, with those ages 18–34 (58%) significantly more likely to report planning a mental health resolution compared with older adults (32% of 45-64-year-olds; 11% of those 65 and over).

A strong majority (82%) of Americans say they plan to make at least one New Year’s resolution for 2026. Physical fitness (44%) and financial goals (42%) remain the top areas of focus, followed closely by mental health (38%), which continues to rise in priority. Other common goals include diet (29%), social or relationship resolutions (29%), and spiritual goals (28%).

“It is encouraging to see more individuals planning to prioritize their mental health in 2026, particularly younger adults,” said APA President Theresa Miskimen Rivera, M.D. “The strategies people are embracing — such as regular physical activity, mindfulness practices, adequate sleep, time in nature and engaging in therapy — reflect a growing recognition that mental health is deeply connected to daily habits. Even small, intentional changes can have a meaningful and lasting impact on overall well-being.”

Looking back on 2025, 63% of Americans rated their mental health as excellent or good, while 28% said it was fair and 8% said it was poor.

Anxiety Heading into the New Year

Heading into 2026, anxiety remains common. Americans report feeling anxious about personal finances (59%), uncertainty about the next year (53%), and current events (49%), with concerns about physical and mental health close behind.

Issues Americans are Anxious About

Issue Percent anxious

(somewhat or very)

Personal finances 59%

Uncertainty of the next year 53%

Current events 49%

Physical health 46%

Mental health 42%

Job security 33%

Relationships with friends and family 32%

Keeping New Year’s resolutions 30%

Romantic relationships 29%

“A new year can bring change, possibility, and uncertainty,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Marketa M. Wills, M.D., M.B.A. “Feelings of anxiousness underscore the importance of paying attention to how we’re doing and taking practical steps, large or small, to support our mental health.”

These results are from the APA’s Healthy Minds Poll, conducted by Morning Consult, Dec. 2–3, 2025, among 2,208 adults. For a copy of the survey results, contact [email protected]. See past Healthy Minds Polls.

American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association, founded in 1844, is the oldest medical association in the country. The APA is also the largest psychiatric association in the world with more than 39,200 physician members specializing in the diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and research of mental illnesses. APA’s vision is to ensure access to quality psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. For more information, please visit www.psychiatry.org.

Continue Reading

-

Portsmouth groups take inspiration from The D-Day Story’s Victory in 80 Objects

The D-Day Story is undertaking several new community engagement activities inspired by its ‘Victory in 80 Objects’ book.

The outreach projects are working with groups in Portsmouth including adults with learning disabilities, students…

Continue Reading

-

Laitinen Returns to Olympic Stage

MINNEAPOLIS – Senior defender Nelli Laitinen is set for her second Olympic appearance with Finland after being named to the roster for the 2026 Olympic Winter Games in Milan, Italy.

Laitinen previously helped Finland capture a bronze medal at…

Continue Reading