- DPM for focus on high-impact sectors for inclusive growth RADIO PAKISTAN

- Pakistan pushes voluntary ethanol blending ChiniMandi

- DPM Dar chairs first meeting of Economic Management Reforms Committee dailyindependent.com.pk

- Committee recommends…

Author: admin

-

DPM for focus on high-impact sectors for inclusive growth – RADIO PAKISTAN

-

China’s BYD set to overtake Tesla as world’s top EV seller

China’s BYD is set to overtake Elon Musk’s Tesla as the world’s biggest seller of electric vehicles (EVs), marking the first time it has outpaced its American rival for annual sales.

On Thursday, BYD said that sales of its battery-powered cars rose last year by almost 28% to more than 2.25 million.

Tesla, which is due to reveal its total sales for 2025 later on Friday, last week published analyst’s estimates suggesting that it had sold around 1.65 million vehicles for the year as a whole.

The US firm has faced a tough year with a mixed reception to new offerings, unease over Musk’s political activities and intensifying competition from Chinese rivals.

In October, Tesla introduced lower-priced versions of its two best-selling models in the US in a bid to boost sales. It had faced criticism that it had been slow to release new and more affordable options to stay competitive.

Musk, who is already the world’s richest man, is tasked with significantly boosting Tesla’s sales and stock market value over the next decade to secure a record-breaking pay package. The deal, which was approved by shareholders in November, could see him getting a payout of as much as $1tn (£740bn).

As part of the agreement, Musk also has to sell a million humanoid robots over the next ten years. Tesla has invested heavily in its “Optimus” product and self-driving “Robotaxis”.

Tesla sales slumped in the first three months of 2025 after a backlash against Musk’s role in US President Donald Trump’s administration.

Besides Tesla, the multi-billionaire’s business interests also include the social media platform X, the rocket firm SpaceX and the Boring Company, which digs tunnels.

Those commitments, along with running Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (Doge), led some investors to suggest that Musk was not focusing enough on Tesla.

Since then Musk has pledged to “significantly” cut back his role in the US government.

Despite BYD’s rapid expansion in recent years, its sales growth slowed in 2025 to the weakest rate in five years.

The Shenzhen-based firm faces mounting competition in China, its key market, from a surge of EV makers like XPeng and Nio.

Still, BYD remains a global EV powerhouse as its prices often undercut rival carmakers.

The company’s rapid expansion – especially in Latin America, South East Asia and parts of Europe – comes despite many countries imposing steep tariffs on Chinese EVs.

In October, BYD said the UK had become its biggest market outside China. The firm said that its sales in Britain surged by 880% in the year to the end of September, driven by strong demand for the plug-in hybrid version of its Seal U sports utility vehicle (SUV).

Continue Reading

-

Depression links to chronic headaches through weight and diet, not physical activity alone

Large population data from Iran show that body weight and iron intake help statistically explain the depression–headache link, while physical activity plays a supporting, indirect role rather than a direct one.

Study: Mediating…

Continue Reading

-

Osaka drawing inspiration from family at United Cup

PERTH (Australia) (AFP) – An excited Naomi Osaka will lean on family ties as she leads Japan in Friday’s opening day at the United Cup in Australia, kicking off her season with a testing clash against former world…

Continue Reading

-

Cold, dry weather expected over most parts: PMD – RADIO PAKISTAN

- Cold, dry weather expected over most parts: PMD RADIO PAKISTAN

- City receives first winter shower Dawn

- Siberian winds likely from 4th: Light rainfall brings change in weather conditions Business Recorder

- Port city welcomes rare chill The Express…

Continue Reading

-

Small shifts in blood sodium may influence human brain excitability

Even within the healthy range, small differences in blood sodium were associated with measurable changes in brain excitability, offering new insight into how subtle physiology may shape neural function in healthy adults.

Study:

Continue Reading

-

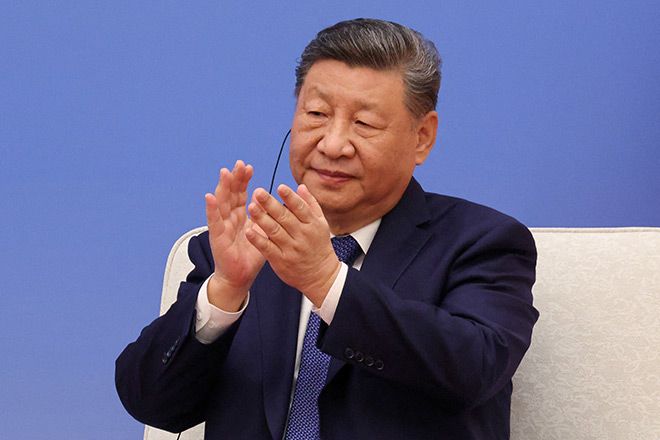

China’s Xi to host South Korea’s Lee in New Year amid Japan tensions

SEOUL/BEIJING–Chinese President Xi Jinping will host South Korean President Lee Jae Myung on a state visit starting on Sunday, signalling Beijing’s intent to strengthen ties with Seoul amidst…

Continue Reading

-

Georgia Holds a 21-12 Sugar Bowl Halftime Lead over Ole Miss

Reviewing The Offense

At the half, Georgia led 21-12. The Bulldogs tallied 190 yards of offense on 31 plays (85-rushing, 105-passing).For the fourth time this season, Georgia did not score in their opening quarter (also vs. UA, @ AU, @ GT) and…

Continue Reading

-

Paul Skenes shaves facial hair, Livvy Dunne reacts

He was the 2024 National League Rookie of the Year. He was the 2025 NL Cy Young Award winner. What does flamethrowing Pirates phenom Paul Skenes have in store for 2026?

Well, for one thing, a new look.

Skenes has shaved the beard he kept during…

Continue Reading