PITTSBURG – The Pittsburg State University women’s basketball team will begin 2026 with a pair of MIAA…

Author: admin

-

Looking back: Space exploration in 2025

As 2025 comes to a close, Planetary Radio looks back on a year that reshaped space exploration, through stunning discoveries, major milestones, unexpected challenges, and the people who carried science forward through it all.

In this episode,…

Continue Reading

-

WhatsApp launches festive features for new year

WhatsApp launches festive features for new year – Daily Times

…Continue Reading

-

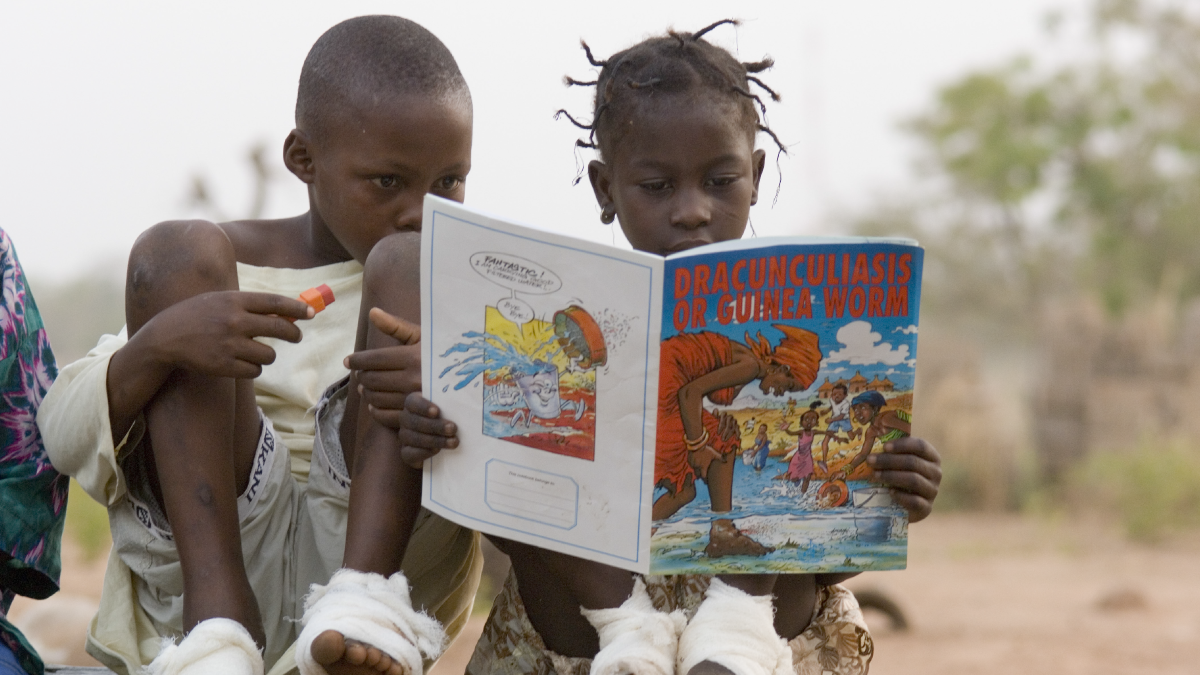

Progress Toward Eradication of Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm Disease) — Worldwide, January 2024–June 2025

Results

Human Cases and Animal Infections

During 2024, a total of 15 human dracunculiasis cases were identified worldwide, including nine in Chad and six in South Sudan (Table 1), one more than the 14 total human cases reported in 2023 (Table…

Continue Reading

-

NASA chief Jared Isaacman says Texas may get a moonship, not space shuttle Discovery

Houston, we may have a problem … for your senators’ plans to bring a NASA space shuttle to Texas.

NASA’s new chief Jared Isaacman said a controversial proposal to move the space shuttle Discovery to Texas from its current home on display at a…

Continue Reading

-

Top 5 Most-Read Multiple Sclerosis Articles of 2025

The past year brought forth critical developments in

multiple sclerosis (MS) research, focusing heavily on optimizing current treatments and advancing novel mechanisms to address the progressive forms of the disease. From definitive data…Continue Reading

-

FCC Implements Categorical Prohibition on All Foreign-Produced UAS and UAS Critical Components

In addition to the restrictions on foreign-produced UAS and UAS critical components, the new Covered List entry also applies stricter prohibitions against “all communications and video surveillance equipment and services listed in Section 1709(a)(1) of the FY25 National Defense Authorization Act.” Section 1709(a)(1) specifically identifies Shenzhen Da-Jiang Innovations Sciences and Technologies Company Limited (DJI) and Autel Robotics as named entities (the “Section 1709 Entities”) and prohibits each entity—and any affiliate, subsidiary, or contractual vehicle of each—from selling communications or surveillance equipment or services generally, in the U.S. market, whether produced domestically or abroad.

The Covered List

Pursuant to the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Act of 2019 (Secure Networks Act), the PSHSB is required to keep an up-to-date list of “communications equipment and services produced or provided by any entity” that, based exclusively on the determination by one or more of four exclusive sources, “poses an unacceptable risk to the national security of the United States or the security and safety of United States persons.” The potential sources, as listed in Section 2 of the Secure Networks Act, include “any executive branch interagency body with appropriate national security expertise” and “an appropriate national security agency.” To date, the Covered List has exclusively focused on communications and surveillance products and services from named entities, each tied to either China or Russia.The effects of the Covered List have been expanding since its inception. Initially, the Secured Networks Act provided that the Covered List prohibits review or approval of equipment authorizations applications of devices for or that incorporate “covered” equipment, as well as the use of Universal Service Fund sources to purchase “covered” equipment and services. More recently, the FCC has expanded the Covered List restrictions into its , and is adopting associated restrictions on certification bodies (Bad Labs) involved in the certification process.

The Foreign UAS Public Notice

As required by Section 1709(a) of the FY2025 NDAA, the FCC received a National Security Determination (NSD) from an Executive Branch interagency body, concluding that, in light of several upcoming mass gathering events, such as the World Cup and Olympics, and the general need to protect U.S. national security and cybersecurity, UAS and UAS critical components produced in foreign countries “pose unacceptable risks, given the threats from unauthorized surveillance, sensitive data exfiltration, supply chain vulnerabilities, and other potential threats to the homeland.”Within a day of receiving the NSD, the PSHSB released the Public Notice to add the following “Foreign UAS Entry” to the Covered List:

Uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) and UAS critical components produced in a foreign country [incorporating the definitions included in the associated National Security Determination] and all communications and video surveillance equipment and services listed in Section 1709(a)(1) of the FY25 National Defense Authorization Act (Pub. L. 118-159).

The Foreign UAS Entry places a broad prohibition on all “UAS” and “UAS critical components” “produced in foreign countries.”

UAS. The Public Notice adopts the existing definition of “UAS” under Section 88.5 of its rules, defined as “the uncrewed aircraft (UA) and its associated elements (communication links, uncrewed aircraft stations, and components that are not onboard the UA, but control the UA) that would be required for the safe and efficient operation of the UA in the airspace of the United States.” The FCC’s rules further define the UA to be “an aircraft operated without the possibility of direct human intervention from within or on the aircraft.”

UAS Critical Components. Both the NSD and FCC recognize that there is no existing definition of “UAS critical components.” Instead, both documents provide a broad, non-exhaustive list of components, and are to be treated as inclusive of any associated software:

- Data Transmission Devices

- Communications Systems

- Flight Controllers

- Ground Control Stations and UAS Controllers

- Navigation Systems

- Sensors and Cameras

- Batteries and Battery

- Management Systems Motors

Produced in a Foreign Country. Notably, and aligned with the stated objectives of the Administration, the prohibition is location-based. The Foreign UAS Entry does not distinguish between UAS and UAS critical components made by foreign entities abroad or those produced outside the United States by U.S.-owned, operated or affiliated entities. Nor does the prohibition differentiate between U.S. allies and competitors or adversaries. The restriction is a blanket prohibition on foreign production unless covered by one of two exemptions.

The Section 1709 Entities. Section 1709 of the FY2025 NDAA provides specific prohibitions for the two entities named in its provisions, separate and apart from the broad restrictions being placed on other location-based UAS and UAS critical component producers. The Section 1709 Entities are subject to a more “traditional” restriction under the Covered List. The two entities—DJI and Autel Robotics—as well as their subsidiaries, affiliates or partners, or any joint venture or technology sharing or licensing agreement with such entities, for any communications or surveillance equipment or services are prohibited from selling any products or services the United States. This means that, with respect to the Section 1709 Entities, the restrictions extend beyond just drone production and would also include any attempts to set up production within the United States, as well.

Implementation

Under FCC rules, equipment on the Covered List is prohibited from receiving or being included as part of an application for equipment authorization. Entities and individuals applying for equipment authorization—a requirement for products that use or incorporate radiofrequencies before being marketed or made commercially available in the United States—are required to certify that the equipment is not and does not include “covered” equipment. This certification will now apply to any entities seeking authorization for UAS or counter-UAS systems in the United States, including those with applications that are currently pending, but not yet granted, before the FCC. Telecommunication Certification Bodies (TCBs) will also be tasked with reviewing equipment authorization applications to assess compliance with the Covered List.***UAS applicants are reminded to ensure applications are up to date and contain accurate certifications given the changes to the Covered List.***

The Exemptions

While most foreign production has been effectively blocked from the U.S. market by the Foreign UAS Entry on the Covered List, the Public Notice does provide two notable exemptions:- Existing Equipment Authorizations. UAS and UAS critical components that have already received an FCC Part 2 equipment authorization may continue to be imported, marketed, and sold in the United States. However, no modifications, amendments or other updates can be made to existing authorizations.

- U.S. Department of War (DOW) or U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Waiver. DOW or DHS can make “a specific determination to the FCC that a given UAS or class of UAS [or given UAS critical component] does not pose such [national security] risks.”

While it is unclear from the Public Notice what a DOW or DHS waiver process will look like, or how it would be implemented by the FCC once made, some standardized waiver process is likely to be implemented. Such processes are also anticipated to cover existing processes like the Defense Contract Management Agency Blue List.

The Public Notice also clarifies that the effects of the listing are not initially retroactive. This action does not affect continued use of drones previously purchased or acquired by consumers. However, moving forward, the FCC may place restrictions on previously-authorized covered equipment, including an outright prohibition, using additional enforcement mechanisms at its disposal.

Takeaways

With immediate effect and without notice, the Foreign UAS Entry substantially expanded the scope and potential impact of what had been expected to be a targeted action regarding the Section 1709 Entities. The consequences of this addition to the Covered List will directly and indirectly affect entities across the UAS and counter-UAS industry. Both international and domestic entities within the UAS ecosystem should carefully review the Public Notice and assess its anticipated impacts on operations, supply chain, and contracts.Companies currently selling or seeking to sell UAS and UAS critical components produced outside the United States that want to continue their U.S. sales should consider actively engaging with their business partners and the U.S. Government to both make a waiver request and avoid contract cancellation prior to adjudication of any such requests.

For more information about the above Public Notice, the Covered List or compliance with these regulations generally, please contact the authors.

Continue Reading

-

Tuning evolvability via plasmid copy number and regulatory architecture

Cameron, D. E., Bashor, C. J. & Collins, J. J. A brief history of synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 381–390 (2014).

Brophy, J. A. N. & Voigt, C. A. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat. Methods 11, 508–520 (2014).

Daniel, R., Rubens, J. R., Sarpeshkar, R. & Lu, T. K. Synthetic analog computation in living cells. Nature 497, 619–623 (2013).

Moon, T. S., Lou, C., Tamsir, A., Stanton, B. C. & Voigt, C. A. Genetic programs constructed from layered logic gates in single cells. Nature 491, 249–253 (2012).

Del Vecchio, D., Abdallah, H., Qian, Y. & Collins, J. J. A blueprint for a synthetic genetic feedback controller to reprogram cell fate. Cell Syst. 4, 109–120.e11 (2017).

Ceroni, F. et al. Burden-driven feedback control of gene expression. Nat. Methods 15, 387–393 (2018).

Huang, H.-H., Qian, Y. & Del Vecchio, D. A quasi-integral controller for adaptation of genetic modules to variable ribosome demand. Nat. Commun. 9, 5415 (2018).

Aoki, S. K. et al. A universal biomolecular integral feedback controller for robust perfect adaptation. Nature 570, 533–537 (2019).

Frei, T., Chang, C.-H., Filo, M., Arampatzis, A. & Khammash, M. A genetic mammalian proportional-integral feedback control circuit for robust and precise gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2122132119 (2022).

Gyorgy, A., Menezes, A. & Arcak, M. A blueprint for a synthetic genetic feedback optimizer. Nat. Commun. 14, 2554 (2023).

Nielsen, A. A. K. et al. Genetic circuit design automation. Science 352, aac7341 (2016).

Jones, T. S., Oliveira, S. M. D., Myers, C. J., Voigt, C. A. & Densmore, D. Genetic circuit design automation with Cello 2.0. Nat. Protoc. 17, 1097–1113 (2022).

Khalil, A. S. & Collins, J. J. Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 367–379 (2010).

Stephanopoulos, G. Synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. ACS Synth. Biol. 1, 514–525 (2012).

Choi, K. R. et al. Systems metabolic engineering strategies: integrating systems and synthetic biology with metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 817–837 (2019).

Pedrolli, D. B. et al. Engineering microbial living therapeutics: the synthetic biology toolbox. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 100–115 (2019).

Cubillos-Ruiz, A. et al. Engineering living therapeutics with synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 941–960 (2021).

Scown, C. D. & Keasling, J. D. Sustainable manufacturing with synthetic biology. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 304–307 (2022).

Gyorgy, A. et al. Isocost lines describe the cellular economy of genetic circuits. Biophys. J. 109, 639–646 (2015).

Ceroni, F., Algar, R., Stan, G.-B. & Ellis, T. Quantifying cellular capacity identifies gene expression designs with reduced burden. Nat. Methods 12, 415–418 (2015).

Yeung, E. et al. Biophysical constraints arising from compositional context in synthetic gene networks. Cell Syst. 5, 11–24.e12 (2017).

Castle, S. D., Grierson, C. S. & Gorochowski, T. E. Towards an engineering theory of evolution. Nat. Commun. 12, 3326 (2021).

Santos-Moreno, J., Tasiudi, E., Kusumawardhani, H., Stelling, J. & Schaerli, Y. Robustness and innovation in synthetic genotype networks. Nat. Commun. 14, 2454 (2023).

Randall, A., Guye, P., Gupta, S., Duportet, X. & Weiss, R. Chapter seven – design and connection of robust genetic circuits. In Voigt, C. (ed.) Synthetic Biology, Part A, vol. 497 of Methods in Enzymology, 159–186 (Academic Press, 2011).

Wagner, A. Robustness and evolvability: a paradox resolved. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 275, 91–100 (2008).

Giver, L., Gershenson, A., Freskgard, P.-O. & Arnold, F. H. Directed evolution of a thermostable esterase. PNAS 95, 12809–12813 (1998).

Yokobayashi, Y., Weiss, R. & Arnold, F. H. Directed evolution of a genetic circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 16587–16591 (2002).

Wang, H. H. et al. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature 460, 894–898 (2009).

Esvelt, K. M., Carlson, J. C. & Liu, D. R. A system for the continuous directed evolution of biomolecules. Nature 472, 499–503 (2011).

Meyer, A. J., Segall-Shapiro, T. H., Glassey, E., Zhang, J. & Voigt, C. A. Escherichia coli “marionette” strains with 12 highly optimized small-molecule sensors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 196–204 (2019).

Sleight, S. C., Bartley, B. A., Lieviant, J. A. & Sauro, H. M. Designing and engineering evolutionary robust genetic circuits. J. Biol. Eng. 4, 12 (2010).

Chlebek, J. L. et al. Prolonging genetic circuit stability through adaptive evolution of overlapping genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 7094–7108 (2023).

Kumar, S. & Hasty, J. Stability, robustness, and containment: preparing synthetic biology for real-world deployment. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 79, 102880 (2023).

Glass, D. S., Bren, A., Vaisbourd, E., Mayo, A. & Alon, U. A synthetic differentiation circuit in Escherichia coli for suppressing mutant takeover. Cell 187, 931–944.e12 (2024).

Rodríguez-Beltrán, J., DelaFuente, J., León-Sampedro, R., MacLean, R. C. & San Millan, A. Beyond horizontal gene transfer: the role of plasmids in bacterial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 347–359 (2021).

Soucy, S. M., Huang, J. & Gogarten, J. P. Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 472–482 (2015).

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O. & Toussaint, A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005).

Carattoli, A. Resistance plasmid families in Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 2227–2238 (2009).

Brinkmann, H., Göker, M., Koblížek, M., Wagner-Döbler, I. & Petersen, J. Horizontal operon transfer, plasmids, and the evolution of photosynthesis in Rhodobacteraceae. ISME J. 12, 1994–2010 (2018).

Manzano-Marin, A. et al. Serial horizontal transfer of vitamin-biosynthetic genes enables the establishment of new nutritional symbionts in aphids’ di-symbiotic systems. ISME J. 14, 259–273 (2020).

San Millan, A., Escudero, J. A., Gifford, D. R., Mazel, D. & MacLean, R. C. Multicopy plasmids potentiate the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0010 (2016).

Rodriguez-Beltran, J. et al. Multicopy plasmids allow bacteria to escape from fitness trade-offs during evolutionary innovation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 873–881 (2018).

Molina, R. S. et al. In vivo hypermutation and continuous evolution. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2, 36 (2022).

Ravikumar, A., Arzumanyan, G. A., Obadi, M. K., Javanpour, A. A. & Liu, C. C. Scalable, continuous evolution of genes at mutation rates above genomic error thresholds. Cell 175, 1946–1957.e13 (2018).

Moore, C. L., Papa, L. J. & Shoulders, M. D. A processive protein chimera introduces mutations across defined DNA regions in vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11560–11564 (2018).

Halperin, S. O. et al. CRISPR-guided DNA polymerases enable diversification of all nucleotides in a tunable window. Nature 560, 248–252 (2018).

Fisher, R. A. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1930.

Wright, S. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16, 97–159 (1931).

Halleran, A. D., Flores-Bautista, E. & Murray, R. M. Quantitative characterization of random partitioning in the evolution of plasmid-encoded traits. Preprint at: https://doi.org/10.1101/594879 (2019).

Rossine, F., Sanchez, C., Eaton, D., Paulsson, J. & Baym, M. Intracellular competition shapes plasmid population dynamics. Science 390, 1253–1264 (2025).

Loveless, T. B. et al. Lineage tracing and analog recording in mammalian cells by single-site DNA writing. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 739–747 (2021).

Segall-Shapiro, T. H., Sontag, E. D. & Voigt, C. A. Engineered promoters enable constant gene expression at any copy number in bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 352–358 (2018).

Alon, U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 450–461 (2007).

Gerland, U. & Hwa, T. Evolutionary selection between alternative modes of gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 8841–8846 (2009).

Marciano, D. C. et al. Negative feedback in genetic circuits confers evolutionary resilience and capacitance. Cell Rep. 7, 1789–1795 (2014).

Gyorgy, A. Competition and evolutionary selection among core regulatory motifs in gene expression control. Nat. Commun. 14, 8266 (2023).

Dublanche, Y., Michalodimitrakis, K., Kümmerer, N., Foglierini, M. & Serrano, L. Noise in transcription negative feedback loops: simulation and experimental analysis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 41 (2006).

Becskei, A. & Serrano, L. Engineering stability in gene networks by autoregulation. Nature 405, 590–593 (2000).

Igler, C., Lagator, M., Tkacik, G., Bollback, J. P. & Guet, C. C. Evolutionary potential of transcription factors for gene regulatory rewiring. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1633–1643 (2018).

Rodríguez-Beltrán, J. et al. Genetic dominance governs the evolution and spread of mobile genetic elements in bacteria. PNAS 117, 15755–15762 (2020).

Cameron, P. et al. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat. Methods 14, 600–606 (2017).

Klein, M., Eslami-Mossallam, B., Arroyo, D. G. & Depken, M. Hybridization kinetics explains CRISPR-Cas off-targeting rules. Cell Rep. 22, 1413–1423 (2018).

Pattanayak, V. et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target dna cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 839–843 (2013).

Jones, D. L. et al. Kinetics of dcas9 target search in Escherichia coli. Science 357, 1420–1424 (2017).

Savageau, M. A. GenetiC Regulatory Mechanisms And The Ecological Niche of Escherichia coli. PNAS 71, 2453–2455 (1974).

Savageau, M. A. Design of molecular control mechanisms and the demand for gene expression. PNAS 74, 5647–5651 (1977).

Savageau, M. A. Demand theory of gene regulation. I. Quantitative development of the theory. Genetics 149, 1665–1676 (1998).

Shinar, G., Dekel, E., Tlusty, T. & Alon, U. Rules for biological regulation based on error minimization. PNAS 103, 3999–4004 (2006).

Gerland, U. & Hwa, T. Evolutionary selection between alternative modes of gene regulation. PNAS 106, 8841–8846 (2009).

Schaerli, Y. et al. Synthetic circuits reveal how mechanisms of gene regulatory networks constrain evolution. Mol. Syst. Biol. 14, e8102 (2018).

Jiménez, A., Cotterell, J., Munteanu, A. & Sharpe, J. Dynamics of gene circuits shapes evolvability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 2103–2108 (2015).

Helenek, C. et al. Synthetic gene circuit evolution: Insights and opportunities at the mid-scale. Cell Chem. Biol. 31, 1447–1459 (2024).

Mihajlovic, L. et al. A direct experimental test of Ohno’s hypothesis. eLife 13, RP97216 (2023).

Sandegren, L. & Andersson, D. I. Bacterial gene amplification: implications for the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 578–588 (2009).

Soskine, M. & Tawfik, D. S. Mutational effects and the evolution of new protein functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 572–582 (2010).

Harrison, E. & Brockhurst, M. A. Plasmid-mediated horizontal gene transfer is a coevolutionary process. Trends Microbiol. 20, 262–267 (2012).

Rouches, M. V., Xu, Y., Cortes, L. B. G. & Lambert, G. A plasmid system with tunable copy number. Nat. Commun. 13, 3908 (2022).

Thieffry, D., Huerta, A. M., Pérez-Rueda, E. & Collado-Vides, J. From specific gene regulation to genomic networks: a global analysis of transcriptional regulation in Escherichia coli. BioEssays 20, 433–440 (1998).

Shen-Orr, S. S., Milo, R., Mangan, S. & Alon, U. Network motifs in the transcriptional regulation network of Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet. 31, 64–68 (2002).

Backwell, L. & Marsh, J. A. Diverse molecular mechanisms underlying pathogenic protein mutations: Beyond the loss-of-function paradigm. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 23, 475–498 (2022).

Billiard, S., Castric, V. & Llaurens, V. The integrative biology of genetic dominance. Biol. Rev. 96, 2925–2942 (2021).

Shepherd, M. J., Pierce, A. P. & Taylor, T. B. Evolutionary innovation through transcription factor rewiring in microbes is shaped by levels of transcription factor activity, expression, and existing connectivity. PLOS Biol. 21, e3002348 (2023).

Wray, G. A. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 206–216 (2007).

Tian, R. et al. Establishing a synthetic orthogonal replication system enables accelerated evolution in E. coli. Science 383, 421–426 (2024).

Rix, G. et al. Continuous evolution of user-defined genes at 1 million times the genomic mutation rate. Science 386, eadm9073 (2024).

Chure, G. et al. Predictive shifts in free energy couple mutations to their phenotypic consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 18275–18284 (2019).

Tack, D. S. et al. The genotype-phenotype landscape of an allosteric protein. Mol. Syst. Biol. 17, e10847 (2021).

Joshi, S. H.-N., Yong, C. & Gyorgy, A. Inducible plasmid copy number control for synthetic biology in commonly used E. coli strains. Nat. Commun. 13, 6691 (2022).

Kumar, P. & Libchaber, A. Pressure and temperature dependence of growth and morphology of Escherichia coli: experiments and stochastic model. Biophys. J. 105, 783–793 (2013).

Paulsson, J. & Ehrenberg, M. Molecular clocks reduce plasmid loss rates: the r1 case. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 179–192 (2000).

Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli k-12 using pcr products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 6640–6645 (2000).

Li, Y. et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing. Metab. Eng. 31, 13–21 (2015).

Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual, 3rd edn (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001).

Gruber, A. R., Lorenz, R., Bernhart, S. H., Neubock, R. & Hofacker, I. L. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W70–W74 (2008).

Riesenberg, S., Helmbrecht, N., Kanis, P., Maricic, T. & Pääbo, S. Improved grna secondary structures allow editing of target sites resistant to CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat. Commun. 13, 489 (2022).

Moreno-Mateos, M. A. et al. CRISPRscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods 12, 982–988 (2015).

Castillo-Hair, S. M. et al. Flowcal: a user-friendly, open source software tool for automatically converting flow cytometry data from arbitrary to calibrated units. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 774–780 (2016).

Krašovec, R. et al. Measuring microbial mutation rates with the fluctuation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 60406 (2019).

Mazoyer, A., Drouilhet, R., Despréaux, S. & Ycart, B. flan: an R Package for inference on mutation models. R. J. 9, 334–351 (2017).

Verrou, K.-M., Pavlopoulos, G. A. & Moulos, P. Protocol for unbiased, consolidated variant calling from whole exome sequencing data. STAR Protoc. 3, 101418 (2022).

Zouein, A., Lende-Dorn, B., Galloway, K. E., Ellis, T. & Ceroni, F. Engineered transcription factor-binding arrays for dna-based gene expression control in mammalian cells. Trends Biotechnol. 43, 2029–2048 (2025).

Lee, T. & Maheshri, N. A regulatory role for repeated decoy transcription factor binding sites in target gene expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 8, 576 (2012).

Lee, J. W. et al. Creating single-copy genetic circuits. Mol. Cell 63, 329–336 (2016).

Continue Reading

-

Lost cavers brought to safety in overnight Matlock Bath rescue

A lost party of cavers were brought to safety in an overnight rescue operation.

The alarm was raised that a group exploring the Ringing Rake Slough system near Matlock Bath had not returned to the surface just before 21:00 GMT on Tuesday.

Derbyshire Cave Rescue Organisation volunteers and Derbyshire Police were called to the scene. Teams went underground at 22:30 and were able to locate the group “after a good search”.

The lost cavers were warmed and then with some digging “in tight areas” were escorted back to the lower entrance near Matlock Mining Museum unharmed just before 05:00 on Wednesday.

Continue Reading