GAME NOTES | Game 11 vs. UT Martin (PDF)

By Thomas Corhern, TTU Athletics Media Relations

COOKEVILLE, Tenn. – Tennessee Tech started off the Ohio Valley Conference race with a strong performance Thursday against Southeast Missouri. Now the…

GAME NOTES | Game 11 vs. UT Martin (PDF)

By Thomas Corhern, TTU Athletics Media Relations

COOKEVILLE, Tenn. – Tennessee Tech started off the Ohio Valley Conference race with a strong performance Thursday against Southeast Missouri. Now the…

The Basics

Drake women’s basketball got back on track with a mid-week MVC win at Indiana State and…

12/19/25

AILA Doc. No. 25121940.

Washington, DC – The Trump Administration has recently expanded the list of countries affected by an indefinite ban and pause on…

The counterintuitive Mpemba effect, where a system relaxes to equilibrium faster under certain conditions, continues to fascinate physicists, and recent attention has focused on its manifestation in systems possessing fundamental symmetries….

12/19/25

AILA Doc. No. 25121940.

Washington, DC – The Trump Administration has recently expanded the list of countries affected by an indefinite ban and pause on…

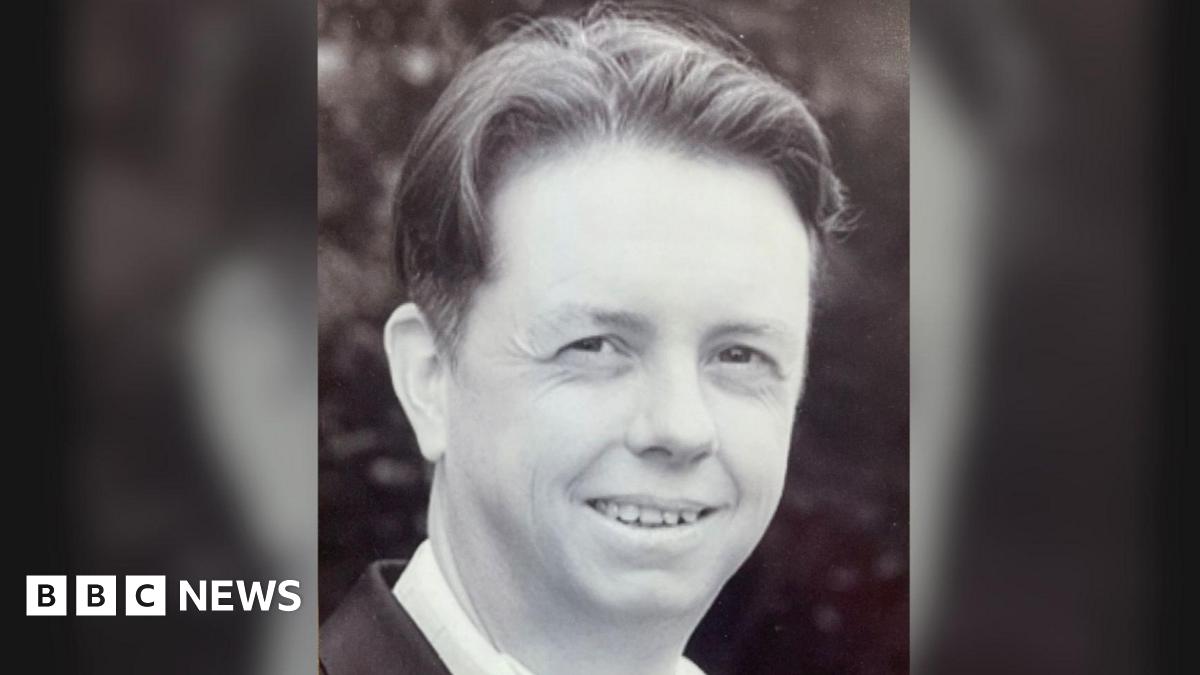

When we try to sum up Lall Kwatra’s life, it’s hard to know where to begin—because his story didn’t begin with comfort or certainty. It began with survival, and it grew into something luminous.

Lall was a child of Partition. When India…

AMES, Iowa – Rachel Van Gorp now adds AVCA Libero of the Year to her lengthy list of 2025 accolades, announced today at the AVCA Banquet.

Van Gorp is the inaugural winner as the AVCA introduced positional Division I awards this season at…

Ottawa residents showed their tremendous support by giving to the 41st OC Transpo / Loblaw Annual Holiday Food Drive held on Saturday, December 13. This is the largest annual, single-day grocery store food drive in Ottawa and has been supporting the Ottawa Food Bank since it began operating in 1984. The annual food drive raised almost 88,000 pounds of food and more than $26,500 for the Ottawa Food Bank and its network of 71 member agencies, and four other Ottawa region food banks. This year’s total is more than twice the weight of a 40-foot bus!

OC Transpo buses and volunteers were on site at several Loblaws, Real Canadian Superstore, Your Independent Grocer and No Frills locations in Ottawa to remind residents of the opportunity to donate. Residents donated food and made monetary donations at participating stores last Saturday. All the food items collected were delivered directly to the Ottawa Food Bank, the Stittsville Food Bank, the Richmond Food Bank, the Barrhaven Food Cupboard, and the Kanata Food Cupboard.

“Visiting the stores and seeing so many Ottawa residents stepping up to donate food and support families in need was truly moving. It reminded me just how caring and generous this city is. A heartfelt thank you to every volunteer, to OC Transpo, and our partners at Loblaw and the Ottawa Food Bank. Together, you’re helping neighbours across Ottawa enjoy a brighter holiday season.”

Mayor Mark Sutcliffe, City of Ottawa

“Local food banks are experiencing the highest demand in their history, with over one in four households in Ottawa struggling to afford enough to eat. From the very beginning, OC Transpo and Loblaw have played a vital role through their annual food drive. During this season of giving, it’s wonderful to see City of Ottawa staff and community members come together to make a meaningful difference for those in need.”

Councillor Glen Gower, Chair, Transit Commission

“The OC Transpo/Loblaw Holiday Food Drive is a yearly tradition that our store colleagues look forward to and are excited to support. As food retailers, with food insecurity continuing to rise, it is really important for us to support our community in the most meaningful way possible, to help put food on the table for those in need. A lot of work goes into this event and we want to thank our partners at the Ottawa Food Bank, OC Transpo, colleagues in our stores, and most importantly, the volunteers that gave up their day and our customers and community that always step up when our city needs it the most.”

Jeff Brierley, Store Manager, Brierley’s Independent Grocer

“Ottawa’s incredible generosity and support of the OC Transpo/Loblaw Holiday Food Drive helps neighbours across our city access nutritious food. With more than one in four households in Ottawa struggling to afford enough healthy food, your contributions are urgently needed and deeply appreciated. Those most at risk of hunger are families with children and individuals living alone. Thanks to your donations of food and funds, nearly 100 community food programs across Ottawa can provide these households with the nourishment they need.”

Rachael Wilson, CEO, Ottawa Food Bank

The Ottawa Food Bank is the main emergency food provider in the National Capital Region and has been serving the community since 1984. The Ottawa Food Bank works in partnership with a network of nearly 100 community food programs that include community food banks, food cupboards, meal programs, kids’ summer nutrition programs, and after-school snack programs. The Ottawa Food Bank network receives more than 588,000 visits for food support annually. Sadly, 37% of Ottawa Food Bank clients are children. With a focus on fresh, and thanks to the community’s support, nearly 8.3 million pounds of food is distributed from the 2001 Bantree Street warehouse each year.

For more information about OC Transpo, including updates and trip planning assistance, visit octranspo.com, use the Travel Planner, or call 613-560-5000. You can also connect with OC Transpo on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram.

NEW: Want a lighter way to stay informed? Sign up for the City News weekly round-up newsletter for brief summaries and links to all the updates you may have missed.

For more information on City programs and services, visit ottawa.ca, call 3-1-1 (TTY: 613-580-2401) or 613-580-2400 to contact the City using Canada Video Relay Service. You can also connect with us through Facebook, Bluesky, X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram.

Mr Scott, from Oakham, Rutland, was admitted to the hospital in December 2015 and diagnosed with leukaemia.

While undergoing chemotherapy, he suffered a known complication of sepsis and was transferred to the intensive care unit.

Mr Heming said…