Scientists have identified a tipping point that has amplified El Niño’s effect on sea ice loss in the Arctic.

For years, researchers have known of a feedback loop linking the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and sea ice coverage at high…

Scientists have identified a tipping point that has amplified El Niño’s effect on sea ice loss in the Arctic.

For years, researchers have known of a feedback loop linking the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and sea ice coverage at high…

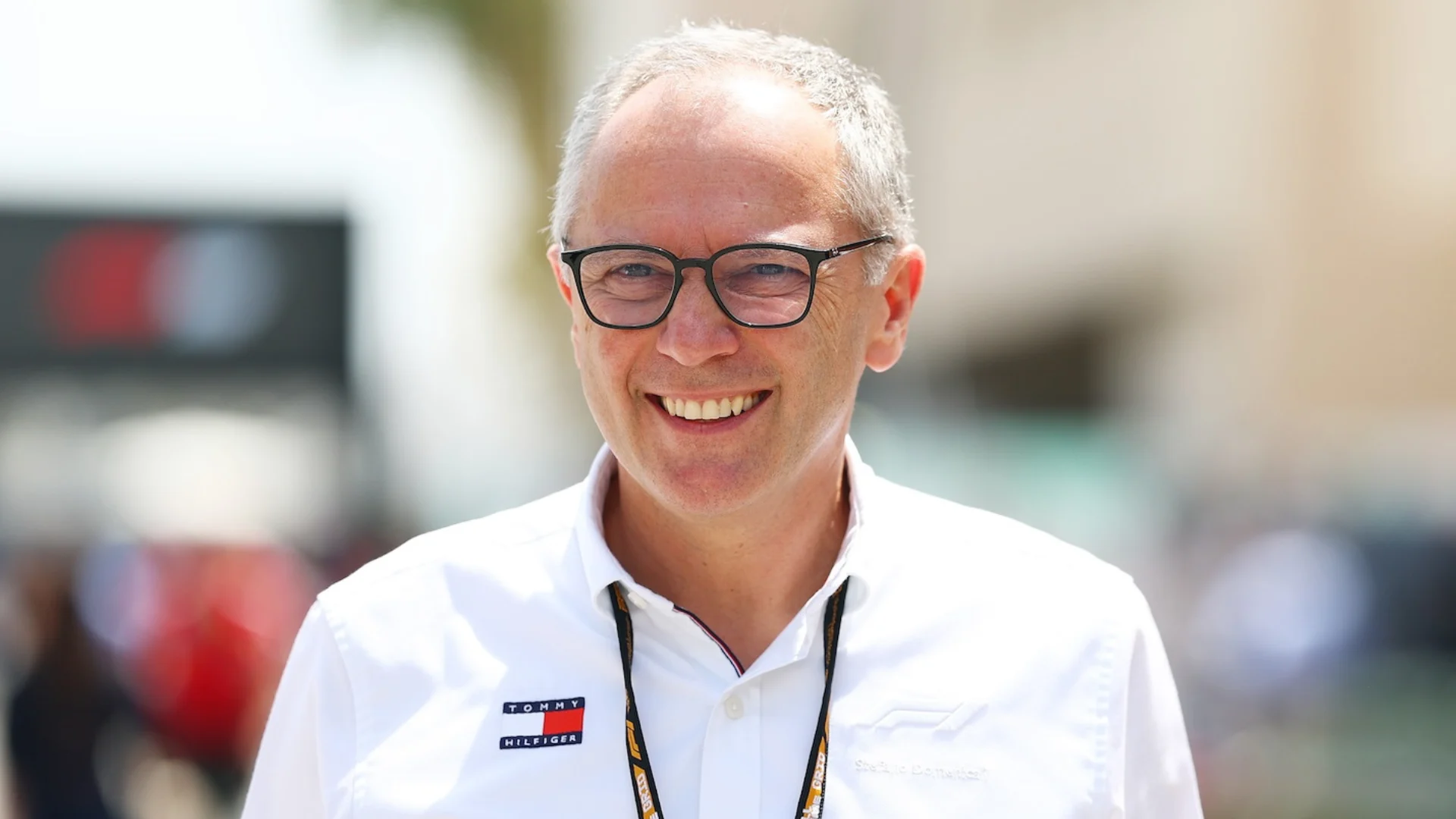

Stefano Domenicali plays a pivotal role in the advancement of Formula 1 through his role as the President and Chief Executive Officer of the championship. As part of Santander’s Driving Tomorrow series, Domenicali discusses how the sport…

NEW YORK – January 29, 2026 – To view the full report please click the following link – Blackstone’s Fourth-Quarter and Full-Year 2025 results.

Blackstone will host its fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 investor conference call via public webcast on January 29, 2026 at 9:00 a.m. ET. To register and listen to the call, please use the following link here.

For those unable to listen to the live broadcast, there will be a webcast replay on the Shareholders section of Blackstone’s website at https://ir.blackstone.com/ beginning about two hours after the event.

About Blackstone

Blackstone is the world’s largest alternative asset manager. Blackstone seeks to deliver compelling returns for institutional and individual investors by strengthening the companies in which the firm invests. Blackstone’s $1.3 trillion in assets under management include global investment strategies focused on real estate, private equity, credit, infrastructure, life sciences, growth equity, secondaries and hedge funds. Further information is available at www.blackstone.com. Follow @blackstone on LinkedIn, X (Twitter), and Instagram.

Contact

Blackstone Public Affairs

New York

+1 (212) 583-5263

The BBC has today published the Board-commissioned independent thematic review of portrayal and representation in BBC content, undertaken by former BAFTA Chair, Anne Morrison, and independent media consultant, Chris Banatvala.

The review assesses…

The hugely successful first series, produced by Fíbín Media and Zoogon Ltd for BBC Gaeilge and TG4, was the first Irish Language crime drama to air on BBC One Northern Ireland, BBC iPlayer and BBC Four.

Sold to 68 countries and streaming under…

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…

The Ambassador of the Arab Republic of Egypt to Pakistan called on the Federal Minister for Health, Syed Mustafa Kamal, to discuss matters of mutual interest with a particular focus on cooperation in the health sector.

During the meeting, both…

United Kingdom Prime Minister Keir Starmer is on a three-day state visit to China as he seeks to deepen economic and security ties with the world’s second-largest economy after years of acrimonious relations.

This is the first trip by a UK prime…