Human specimens

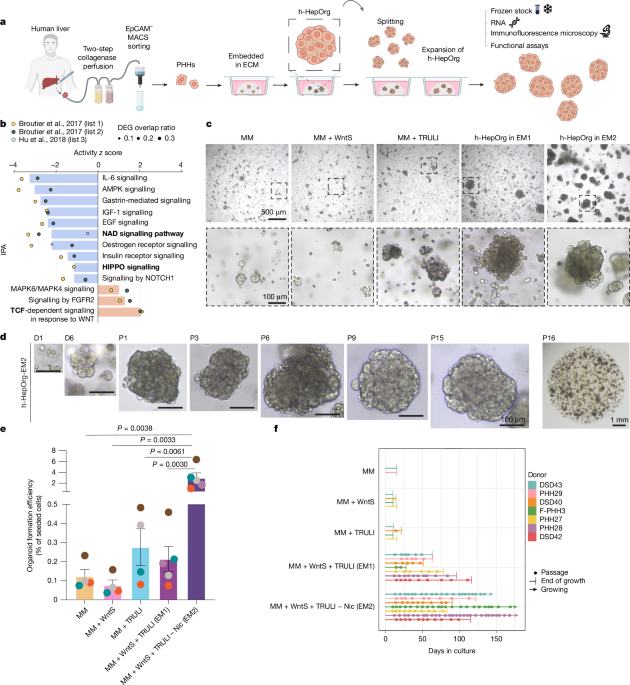

All human liver tissues used in this study were obtained after informed consent was obtained from patients undergoing operations at either the Department of Visceral, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery (VTG), University Hospital Carl…

All human liver tissues used in this study were obtained after informed consent was obtained from patients undergoing operations at either the Department of Visceral, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery (VTG), University Hospital Carl…

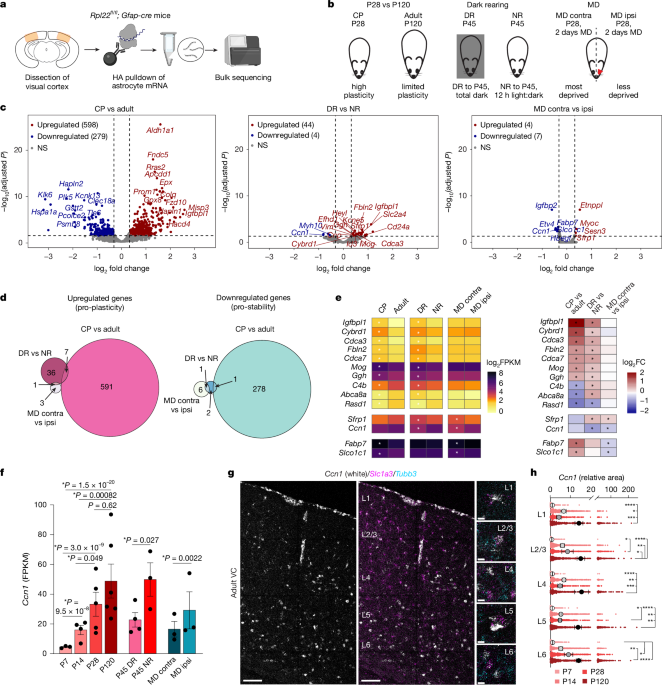

All animal experiments were approved by the Salk Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Rats and mice were typically housed with a standard 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle in the Salk Institute animal facilities,…

Young adult male and female mice were used between 2 and 4 months of age at the time of experimental procedures. C57BL/6 J mice (JAX: 000664) were used for experiments requiring a wild-type background. For RNA-seq of astrocyte-specific…

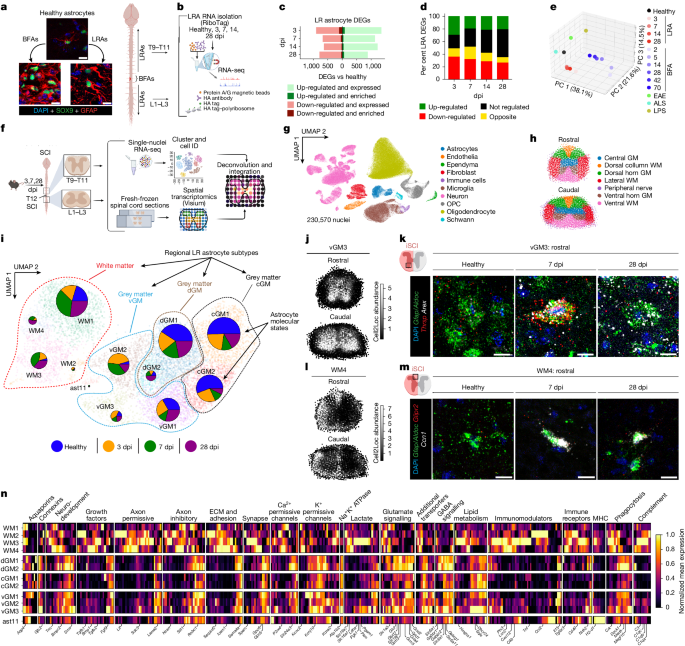

All experiments were performed in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations as approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of the Broad Institute (protocol #IBC-2017-00146). All animal experiments were approved…

The next Prize Pack Series is on the way, Trainers—starting January 1, 2026, Pokémon TCG Prize Pack Series Eight will be available at participating Play! Pokémon Stores. At your local Play! Pokémon…

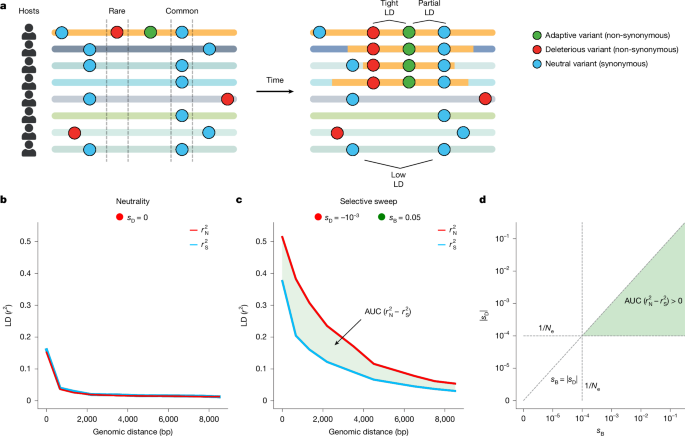

Garud, N. R., Good, B. H., Hallatschek, O. & Pollard, K. S. Evolutionary dynamics of bacteria in the gut microbiome within and across hosts. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000102 (2019).

…

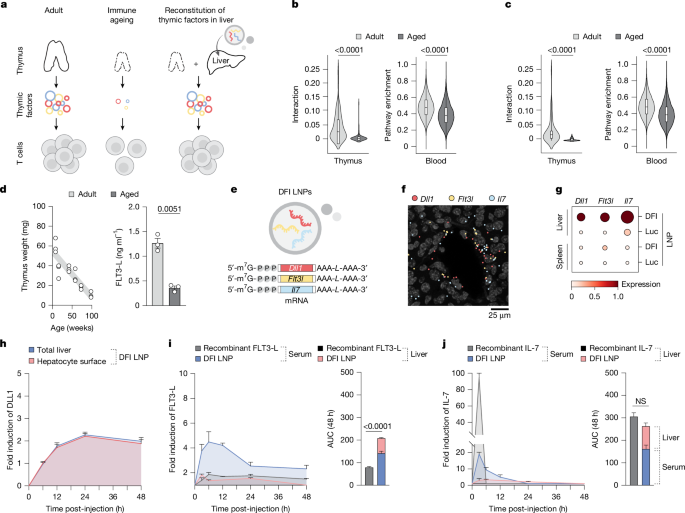

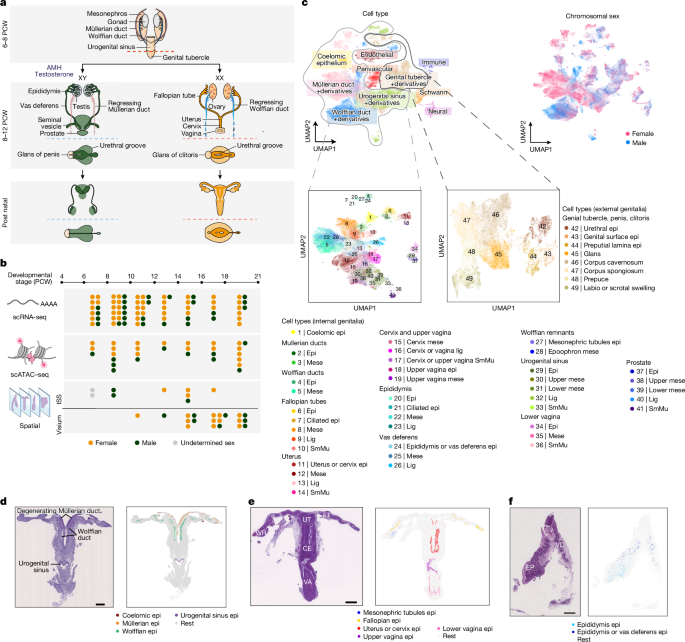

Fetuses were obtained after voluntary terminations of pregnancy, which were performed either via medical or surgical procedures. The termination methods used did not compromise the integrity or morphology of the fetuses analysed in this…

Zhang, A., Sun, H., Wang, P., Han, Y. & Wang, X. Recent and potential developments of biofluid analyses in metabolomics. J. Proteomics 75, 1079–1088 (2012).

Google Scholar

…