FIA, Formula 1 Group and all 11 race teams officially sign the ninth Concorde Agreement, securing strength and stability for the sport in pivotal five-year agreement

– Multi-year Concorde…

– Multi-year Concorde…

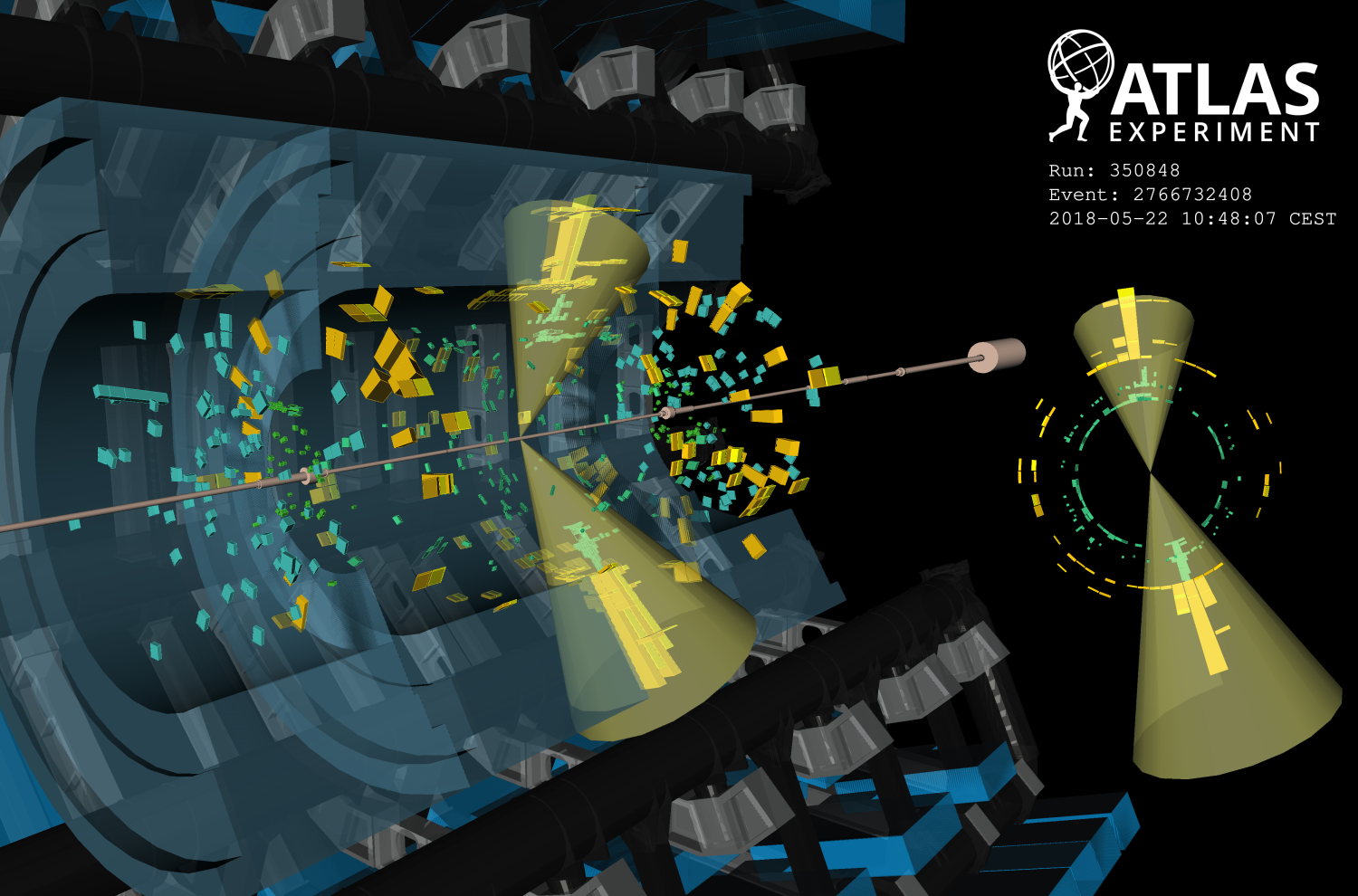

Nature loves symmetry. Nowhere is this more evident than at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), where the vast majority of proton-proton collisions result in a strikingly symmetrical signature: two concentrated sprays of hadrons (jets) emerging…

From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and…

Earth’s orbit is starting to look like an LA freeway, with more and more satellites being launched each year. If you’re worried about collisions and space debris making the area unusable – and you should be – scientists have proposed a new…

Lombard Odier is proud to have earned a Bronze Effie Award at the 2025 Effie Awards Europe, a globally recognised symbol of marketing effectiveness. This honour celebrates the campaign Rethinking Through the Noise, an idea born from our rethink…

The Nordic Storm have announced their third wide receiver for the 2026 season. After confirming Brendan Beaulieu and Simon Føns, the franchise has now extended Edvin Almeida, securing their second homegrown receiver for the upcoming campaign.