by Sophie Jenkins

London, UK (SPX) Feb 08, 2026

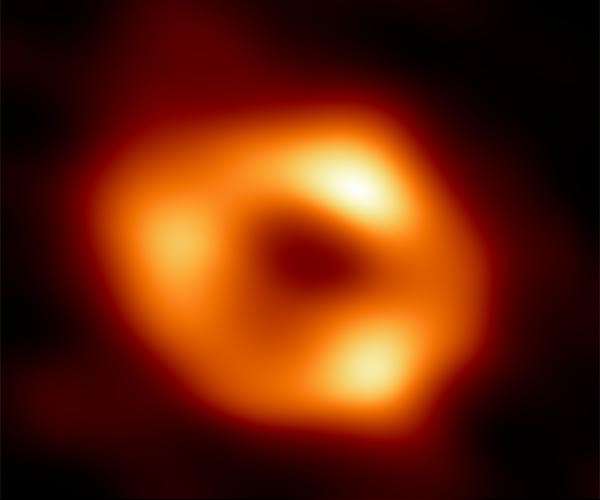

Our Milky Way galaxy may not host a supermassive black hole at its center but instead an enormous concentration of dark matter that exerts an equivalent gravitational influence on…

by Sophie Jenkins

London, UK (SPX) Feb 08, 2026

Our Milky Way galaxy may not host a supermassive black hole at its center but instead an enormous concentration of dark matter that exerts an equivalent gravitational influence on…

by Riko Seibo

Tokyo, Japan (SPX) Feb 08, 2026

The shimmering curtains of the aurora form when energetic electrons plunge into Earths upper atmosphere and collide with atoms and molecules, releasing light across the polar skies. For…

by Jim Shelton

New Haven CT (SPX) Feb 08, 2026

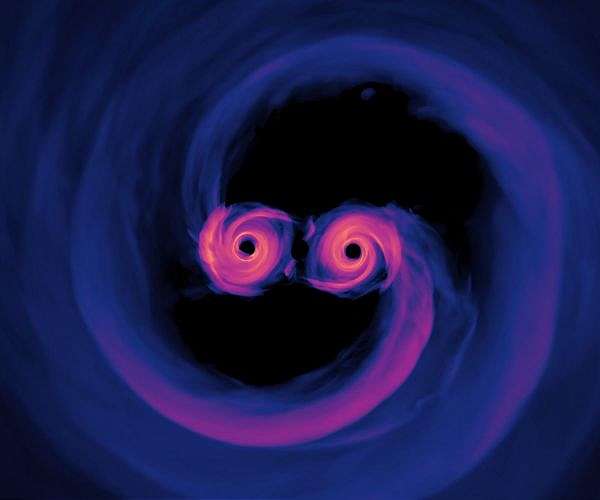

An international collaboration of astrophysicists that includes researchers from Yale has created and tested a detection system that uses gravitational waves to map out the locations…

by Erica Marchand

Paris, France (SPX) Feb 08, 2026

Around 14 hours before a partial solar eclipse crossed the Dolomites in northern Italy, a cluster of spruce trees showed a sharp, synchronized rise in electrical activity. A new…

NEW DELHI: Global terror outfit Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the deadly blast at a Shia mosque in Islamabad that led to over three dozen casualties on Friday. Toll rose to 36 on Saturday after some critically injured people died…

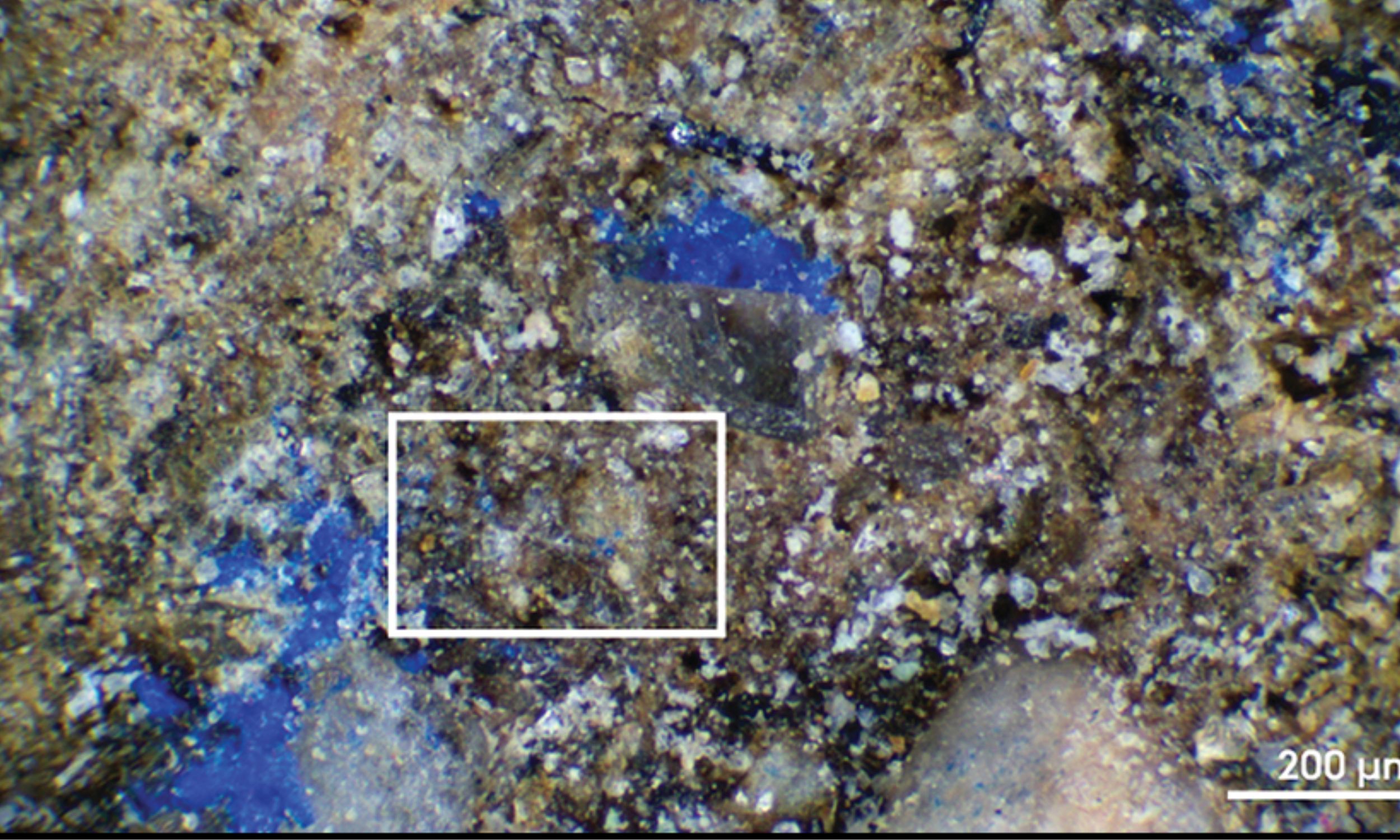

A small stone long dismissed as an ordinary Ice Age tool has been shown to contain the oldest known blue pigment ever documented in Europe.

The discovery pushes the use of blue thousands of years earlier than expected and reshapes how…

Shiffrin is aware that the exposure at the Olympics is greater than during the World Cup season, but she is happy to accept the pressure that comes with it.

“The Olympics give us the chance to…

Retailers say demand for the iPhone Air has tripled in recent weeks, after its price fell by around VND7 million (US$270) compared with its launch price four months ago.

“Following the…

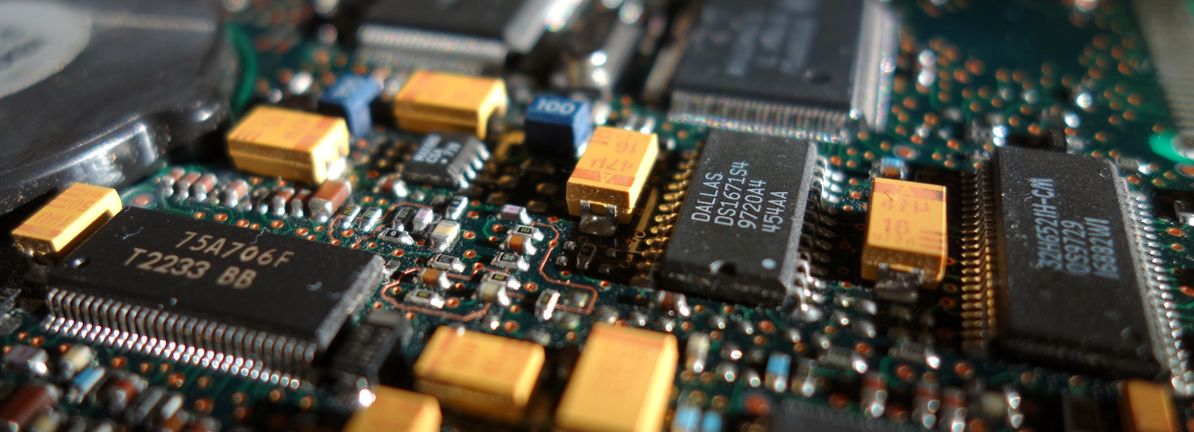

In early February 2026, Monolithic Power Systems reported past fourth-quarter and 2025 results with higher sales year on year, issued first-quarter 2026 revenue guidance of US$770.0 million to US$790.0 million, announced a quarterly dividend increase from US$1.56 to US$2.00 per share, and outlined the planned retirement of long-serving CFO Bernie Blegen, with Corporate Controller Rob Dean to become interim CFO.

An interesting angle for investors is how the company is pairing a sizable dividend boost and above-consensus revenue outlook with a carefully managed finance leadership transition designed to maintain continuity.

With this backdrop, we’ll examine how the combination of stronger-than-expected revenue guidance and a higher dividend shapes Monolithic Power Systems’ investment narrative.

Capitalize on the AI infrastructure supercycle with our selection of the 33 best ‘picks and shovels’ of the AI gold rush converting record-breaking demand into massive cash flow.

To own Monolithic Power Systems today, you need to be comfortable paying a rich multiple for a company that is leaning into growth, capital returns and a complex end-market mix. The latest quarter reinforced that picture: revenue continued to rise year on year, Q1 2026 guidance of US$770.0 million to US$790.0 million came in above prior expectations, and the dividend was lifted to US$2.00 per share, even as earnings over the past year were lower than the prior period and net margins compressed. Those moves, together with a share price that has already run hard, keep execution risk and valuation front and center over the short term. The planned CFO transition, with a long-tenured insider stepping in as interim, appears designed to limit disruption rather than change the thesis in a material way.

However, investors should be aware that paying up for strong guidance does not remove valuation and execution risk. Monolithic Power Systems’ shares are on the way up, but could they be overextended? Uncover how much higher they are than fair value.

Twelve Simply Wall St Community fair values span roughly US$428 to about US$1,198 per share, underlining how far apart private investors can be on MPWR. Set against rich current multiples and a higher dividend commitment, that spread invites you to weigh differing views on how much growth and margin resilience the business can realistically deliver.

Explore 12 other fair value estimates on Monolithic Power Systems – why the stock might be worth as much as $1198!