In their final season under their former guise, Kick Sauber ended 2025 in ninth place of the Teams’ Championship – but it was arguably a stronger season than that result would suggest, with the squad scoring decent points and gaining momentum…

Author: admin

-

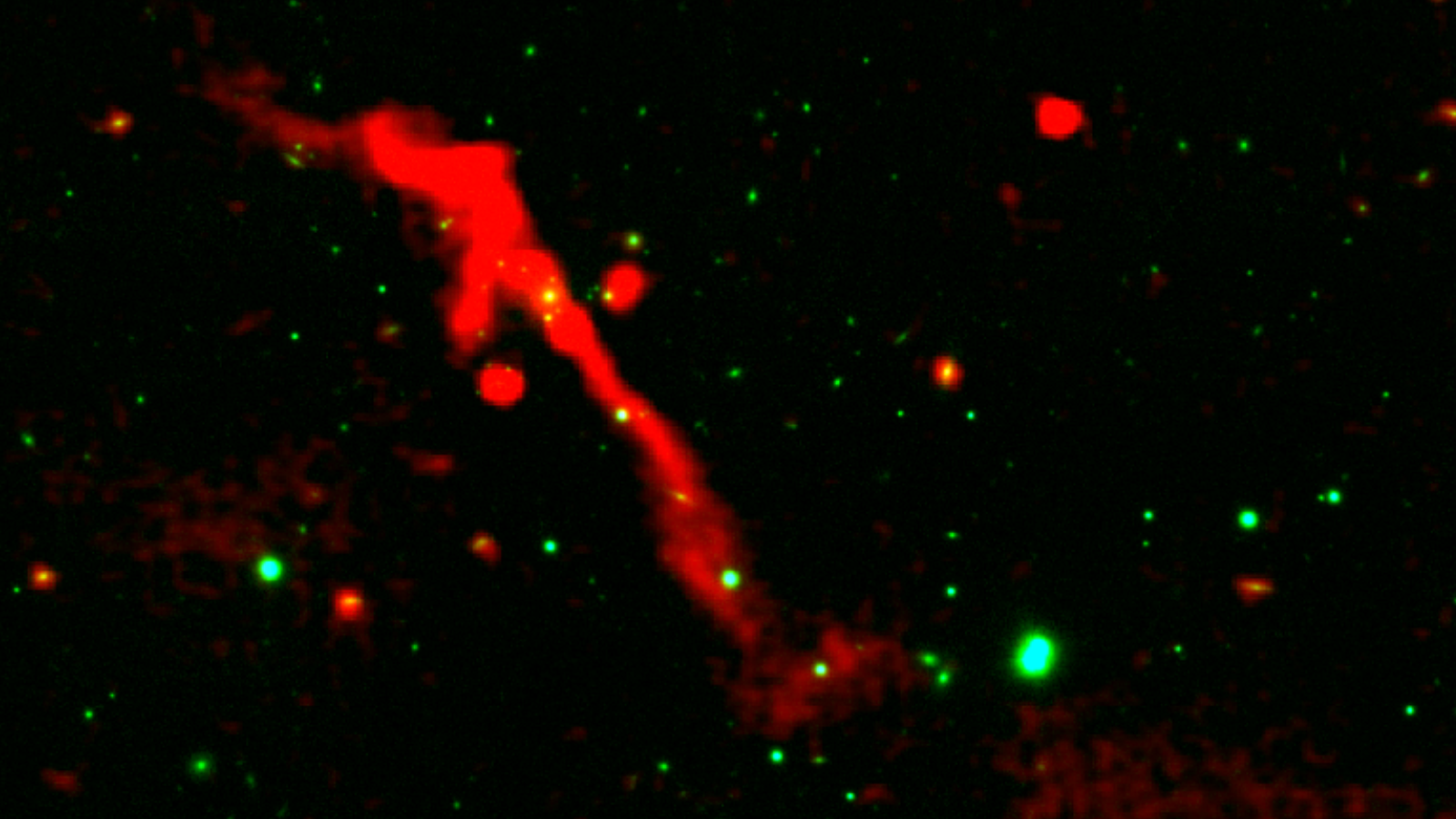

Reborn black hole seen erupting across 1 million light-years of space like a cosmic volcano

Astronomers have discovered a once-dormant supermassive black hole springing back to life in a very dramatic and spectacular fashion, acting as a “cosmic volcano” blasting out an eruption that stretched out for 1 million light-years. The…

Continue Reading

-

The Last Common Ancestor of Humans and Neanderthals Is Found, in Morocco

We are eternally fascinated by the mystery of our origins. Dust and a divine spark satisfied many until the advent of evolution theory and paleontology, which generated a broad consensus that our species originated in Africa. But doubts had…

Continue Reading

-

Interferon response key to fighting rhinovirus infections in nasal passages

When a rhinovirus, the most frequent cause of the common cold, infects the lining of our nasal passages, our cells work together to fight the virus by triggering an arsenal of antiviral defenses. In a paper publishing January 19 in…

Continue Reading

-

Marvel Rivals Championship Season 6 schedule and format revealed – Esports Insider

- Marvel Rivals Championship Season 6 schedule and format revealed Esports Insider

- Deadpool Rockets ‘Marvel Rivals’ To Eight Month Playercount Record Forbes

- Assessing NetEase (SEHK:9999) Valuation After Marvel Rivals Season 6 Deadpool Update

Continue Reading

-

US Immigrant Visa Processing Will Be Suspended For 75 Countries | Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer

Effective January 21, 2026, the U.S. Department of State will indefinitely pause the issuance of immigrant visas (connected to the permanent residence process) for nationals of 75 countries in an expansion of its internal efforts to assess

Continue Reading

-

India, UAE sign $3 billion LNG deal, agree to boost trade and defence ties at leaders' meeting – Reuters

- India, UAE sign $3 billion LNG deal, agree to boost trade and defence ties at leaders’ meeting Reuters

- India, UAE sign $3 billion LNG deal, agree to boost trade and defence ties at leaders’ meeting Dawn

- Sheikh Al Nahyan visits India: Inside the…

Continue Reading

-

ECP seeks amendement in Elections Act to ensure timely conduct of local govt polls – Dawn

- ECP seeks amendement in Elections Act to ensure timely conduct of local govt polls Dawn

- ECP urges amendments to Section-219 of the Elections Act, 2017 The Nation (Pakistan )

- Elusive LG elections in Islamabad Business Recorder

- Timely LG polls: ECP…

Continue Reading

-

On Tuesday 20 January the Olympic Torch crosses the Veneto region and arrives in Vicenza

On Tuesday 20 January, the Flame Journey of the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games will cross the lower Veronese and Polesine areas for its forty-fourth stage, a route that follows the historical streets of the Venetian plain between…

Continue Reading