- Howard 84-58 Delaware State (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap ESPN

- Okojie, Bryson score 16 each to help Howard beat Delaware State 84-58 Caledonian Record

- Delaware State stays winless in MEAC men’s basketball Bay to Bay News

- How to watch Howard Bison vs….

Author: admin

-

Howard 84-58 Delaware State (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap – ESPN

-

Alabama A&M 100-91 Jackson State (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap

HUNTSVILLE, Ala. — — Kintavious Dozier scored 31 points to lead Alabama A&M over Jackson State 100-91 on Monday night.

Dozier shot 9 of 14 from the field, including 4 for 8 from 3-point range, and went 9 for 10 from the free-throw…

Continue Reading

-

Florida A&M 91-84 Grambling (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap – ESPN

- Florida A&M 91-84 Grambling (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap ESPN

- Florida A&M protects home court in Patrick Crarey III return game with Grambling Yahoo Sports

- HBCU coaching carousel creates intriguing matchup HBCU Gameday

- Patrick Crarey returning to…

Continue Reading

-

Northwestern State 64-63 UT Rio Grande Valley (Jan 12, 2026) Game Recap

NATCHITOCHES, La. — — Micah Thomas had 17 points and Izzy Miles made the first of two free throws with one second left to rally Northwestern State to a 64-63 victory over UT Rio Grande Valley on Monday night.

Thomas also had five…

Continue Reading

-

Trump says nations doing business with Iran face 25% tariff on US trade – Reuters

- Trump says nations doing business with Iran face 25% tariff on US trade Reuters

- Iran protests updates: Trump slaps US tariff Iran’s trading partners Al Jazeera

- Trump announces tariffs on Iran trade partners as protest toll rises Dawn

- Trump…

Continue Reading

-

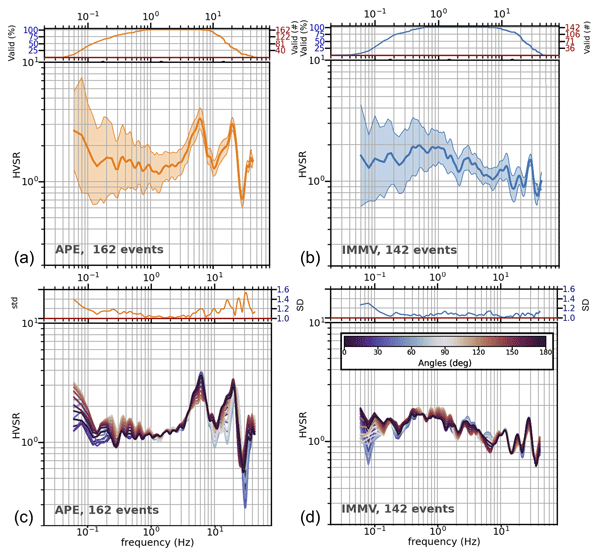

The quest for reference stations at the National Observatory of Athens, Greece

Ancheta, T. D., Darragh, R. B., Stewart, J. P., Seyhan, E., Silva, W. J., Chiou, B. S. J., Wooddell, K. E., Graves, R. W., Kottke, A. R., Boore, D. M., Kishida, T. and Donahue, J. L.: NGA-West2 Database, Earthquake Spectra, 30, 989–1005,

Continue Reading

-

Issue Brief on “Pakistan Turkiye Azerbaijan Trilateral Cooperation”

The trilateral partnership between Pakistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkiye represents an evolving model of strategic cooperation rooted in shared principles and…

Continue Reading

-

WHO South-East Asia marks 15 years since the last case of wild poliovirus; polio legacy continues to drive broader public health gains

Fifteen years after recording its last case of wild poliovirus, the WHO South-East Asia Region with a quarter of the world’s population, continues to sustain its polio-free status while harnessing innovations and lessons from the polio…

Continue Reading

-

Pakistani students, pilgrims return from Iran via Gwadar

Amid ongoing violent protests in different parts of Iran, Pakistani students studying at various universities and religious institutions, along with pilgrims visiting holy sites, have started returning to Pakistan through the Gwadar route.

…

Continue Reading

-

Intra-day update: rupee registers gain against US dollar – Business Recorder

- Intra-day update: rupee registers gain against US dollar Business Recorder

- Rupee registers gain against US dollar Business Recorder

- Foreign exchange rates in Pakistan for today, January 13, 2026 Profit by Pakistan

- Today Open Market Currency Rates in Pakistan – Dollar, Euro, Dirham, Riyal – 12 Jan 2026 Daily Pakistan

- Rupee gains one paisa against dollar Daily Times

Continue Reading