January 12, 2026 — The Walton High School (WHS) Sports Hall of Fame (HOF) recently introduced its 2026 class of honorees. Former Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher Marc Pisciotta and National Football League (NFL) draftee Mike Travis were…

Author: admin

-

Valkyries Name Denise Romero Vice President, Basketball Administration

Romero Brings Over 20 Years Of Basketball Administration And Logistics Experience To The Valkyries

The Golden State Valkyries have named Denise Romero as Vice President, Basketball Administration, it was announced today. Romero, who has over 20…

Continue Reading

-

Gold Trading at a Record High as Powell Says Trump is Attacking the Federal Reserve's Independence – marketscreener.com

- Gold Trading at a Record High as Powell Says Trump is Attacking the Federal Reserve’s Independence marketscreener.com

- Gold cracks $4,600/oz as Fed uncertainty fans safe-haven rush Reuters

- Gold prices hit record high above $4,600/oz on Iran unrest, Fed indictment threat Investing.com

- Power price rallies push gold, silver to record highs on safe-haven demand KITCO

- Gold, silver hit record highs as US Justice Dept probe targets Federal Reserve Geo News

Continue Reading

-

how Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet takes from – and mistakes – Shakespeare

In her eighth novel Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell imagines the short life and tragic death of Shakespeare’s only son, aged 11, in 1596. Although it is not known how Hamnet died, O’Farrell attributes his death to the plague. She creates a…

Continue Reading

-

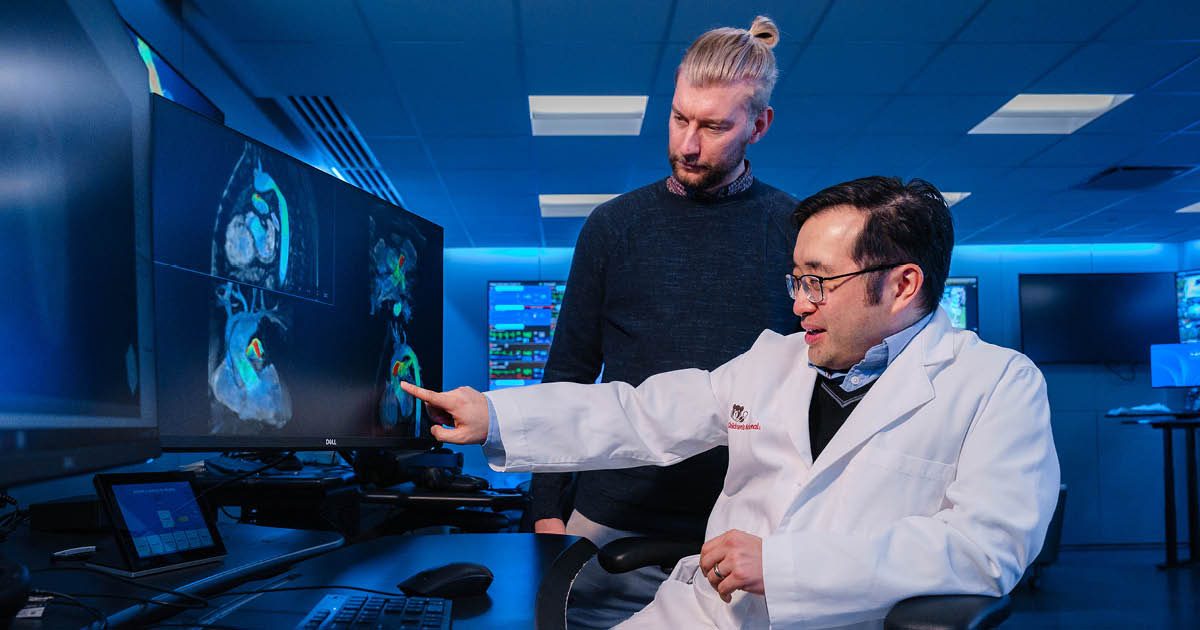

3D modeling and virtual visualization takes cardiac surgery planning to the next level

Why it matters

Those hours can be critical for surgeries on a timeline, such as partial heart transplants. Recently, Dr. O’Hara and Yue-Hin Loke, MD, director of the 3D Cardiac Visualization Laboratory, worked together to provide computed…

Continue Reading

-

Snow fleas use their tail to jump around the ice

Not eating yellow snow is obviously wise advice, but how about snow that looks like a poppy seed bagel? You should also avoid that too, because those “seeds” may actually be tiny critters commonly called snow fleas.

As a video taken at the…

Continue Reading

-

JACC Debuts Data Digest on CV Health in the United States

The annual report covers the five most impactful cardiovascular diseases, aiming for accountability and action.

JACC, the American College of Cardiology’s flagship journal, has embarked on a new project: an annual look at key evidence…

Continue Reading

-

New Vulnerability Identified in Aggressive Breast Cancer

Article Content

Researchers at University of California San Diego have identified a previously unrecognized treatment target for triple‑negative breast cancer (TNBC), the most aggressive subtype of breast…

Continue Reading

-

KE Continues Crackdown Against Electricity Theft, Removes 160kg of Illegal Connections in Rind Goth, Bin Qasim Town – K-Electric

Karachi, January 12, 2026: In order to reduce distribution loss, K-Electric (KE) continued its operation against electricity theft, removing 80 illegal electricity connections weighing nearly 160kg from unmetered commercial shops and…

Continue Reading

-

Weather in city turns extremely icy

LAHORE – The city’s weather is extremely cold, with a temperature of 7 degrees Celsius recorded. According to the Meteorological Department, the intensity of the cold will increase in the coming days, and a slight change in the weather…

Continue Reading