“It is almost unbelievable what the Uppsala researchers achieved under the conditions they had. But when the study ended, the ability to continue providing treatment unfortunately disappeared,” says Stephan Mielke, professor at the Department of Laboratory Medicine at Karolinska Institutet.

He describes how Sweden, initially at the forefront, fell behind. Major companies chose other countries for their trials. The first approved CAR-T therapy in Europe, Tisa-Cel, did not receive an NT Council recommendation for lymphoma due to uncertainties in the health-economic assessment.

“It was a strange situation. Sweden was so early with this innovative product, but when patients in other countries received commercial CAR-T cells, Swedish patients did not. That was the situation when I was recruited in 2017,” says Mielke, who also serves as medical lead for cell therapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation at Karolinska University Hospital.

He worked to certify the hospital for collaboration with industry on CAR-T cells. In November 2019, the first Swedish treatment in routine care was given, and Mielke was one of the treating physicians.

“The same day we signed the agreement with the company, we started the first treatment. It was a child who was very, very ill. I won’t go into details, but the situation has truly improved for that child,” he says.

Good results in routine care

Together with other researchers, he recently published a summary in Leukemia on the first hundred patients treated with CAR-T in Swedish routine care. All had blood cancers involving diseased B cells and were severely ill; for many, all other options were exhausted.

Adults treated between 2019 and 2024 had a 67 percent probability of being alive two years post-treatment, a result that according to the authors are better than observed in other European countries. Most who died during the period died from their cancer; some died in connection with treatment.

CAR-T cells are extraordinarily potent–in both efficacy and potential side effects, Stephan Mielke explains.

“You only grasp the magnitude when you see it,” he says.

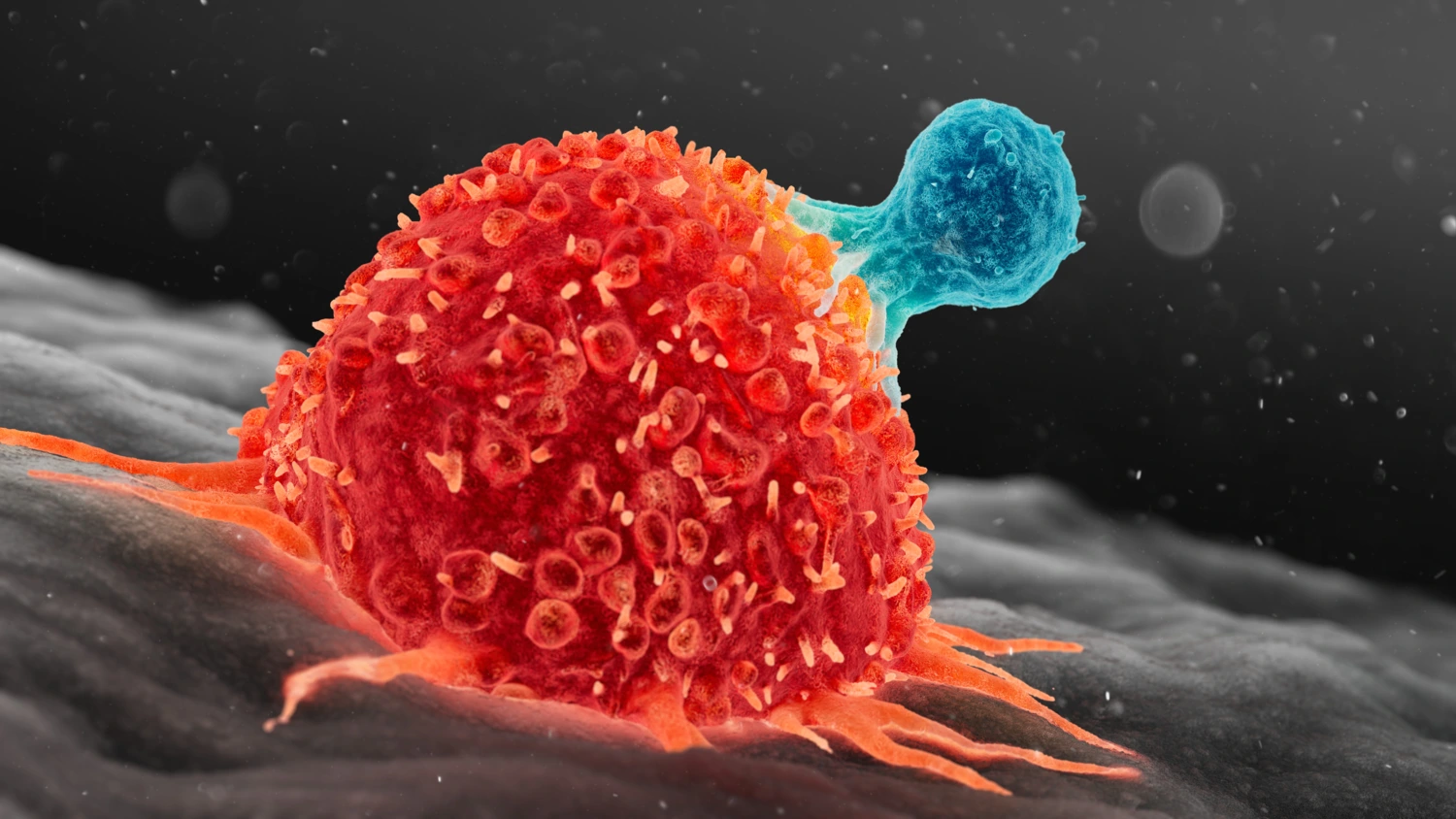

CAR-T cells are manipulated T cells, normally part of the immune system. They are collected from the patient’s blood and modified in the lab, where they are given a new receptor which replaces the one they normally use to recognise threats in the bloodstream.

This receptor includes an antibody component that draws them like magnets to specific cells, which they then destroy.

“It happens at breakneck speed–the immune reaction is powerful. If there are many cancer cells, we can see a reaction similar to some COVID patients–cytokine storms, where the immune response is so strong that the body is harmed,” says Mielke.

Healthcare has become progressively better at managing such side effects, but they may still require hospital care. CAR-T is a rapidly advancing modality–the most widely used ATMP. Five CAR-T medicines are now recommended by NT Council for routine use in Sweden, for various forms of lymphoma, leukaemia and myeloma, all B-cell diseases.

It is no coincidence that early CAR-T therapies target B cells: people can live without B cells. If CAR-T cells become overzealous and kill both diseased and healthy cells, patients with B-cell disease may still do well.

Tested against autoimmune diseases

Initial efforts to broaden CAR-T have targeted other B-cell–driven diseases, including autoimmune conditions such as several rheumatic diseases and multiple sclerosis.

Smaller studies have already shown that patients with severe SLE or myositis–potentially fatal rheumatic conditions–have appeared healthy after CAR-T and were able to stop their rheumatology drugs. Others with severe systemic sclerosis saw marked symptom improvement but still needed medication, as described in a 2024 study with 15 months of follow-up.

Mielke foresees CAR-T taking a larger role in care. A next step is in vivo manufacturing–producing CAR-T inside the body rather than in the lab. Another avenue involves allogeneic T cells from healthy donors, potentially enabling off-the-shelf cell products.

Intense research is also underway to make CAR-T effective against solid tumours, not just B-cell diseases. The challenge is identifying targets truly specific to tumours, clearly distinguishing diseased from healthy cells.

According to Mielke, it is only a matter of time before this is solved.

“We will make progress. There are so many researchers invested in this,” he says.

In short: CAR-T treatments are expected to grow in number, cover more diseases, and become more sophisticated.

A similar trajectory is underway in gene therapy. Many monogenic diseases are in the focus of researchers, while attention also turns to more complex conditions involving multiple genes and proteins–the field’s momentum is high.

“We are only at the beginning of this journey. I think all healthcare in future will have an ATMP element–from eyes, ears and teeth to reproduction, ageing and memory, and everything in between. We can’t yet imagine it,” says Mielke.

High price tag but great potential benefits

The price tag is equally hard to imagine. New gene therapies, often given once, are extraordinarily expensive, taking turns at being called “the world’s most expensive drug.” Right now haemophilia therapy Hemgenix is described as the most expensive, recently it was Libmeldy for MLD, and before that Zolgensma for SMA. In Sweden, the price for a single dose is around or above 30 million kronor.

That can alarm any regional policymaker. Even if each patient group is tiny, together they add up–especially as more medicines reach the market.

Health-economic evaluations for ATMPs are hard for several reasons. How should the cost of a single expensive one-off dose be weighed against savings over time when other treatments are no longer needed? Annual budgets are a poor fit. It is also difficult to judge how durable cures really are when long-term studies are lacking.

These issues remain unresolved. Proposed solutions include instalment-like payment models, where regions pay over a longer period, and outcomes-based agreements, where companies are paid only if a certain effect is achieved.

“Making these medicines available to patients is the greatest challenge,” says Mielke.