Category: 3. Business

-

.jpg)

Scientists Report Deterministic Entanglement-Assisted Quantum Communication Over 20-km Fiber Channel

Insider Brief

- Researchers experimentally demonstrated deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication over 20.121 km of optical fiber, extending dense coding from laboratory-scale tests to metropolitan-scale distances.

- The work uses an improved continuous-variable quantum dense coding scheme that independently transmits entangled states and local oscillator beams to reduce fiber noise and prevent decoding with classical coherent states alone.

- Measurements show higher signal-to-noise ratios and increased channel capacity than classical communication across long fiber links, particularly at larger average photon numbers.

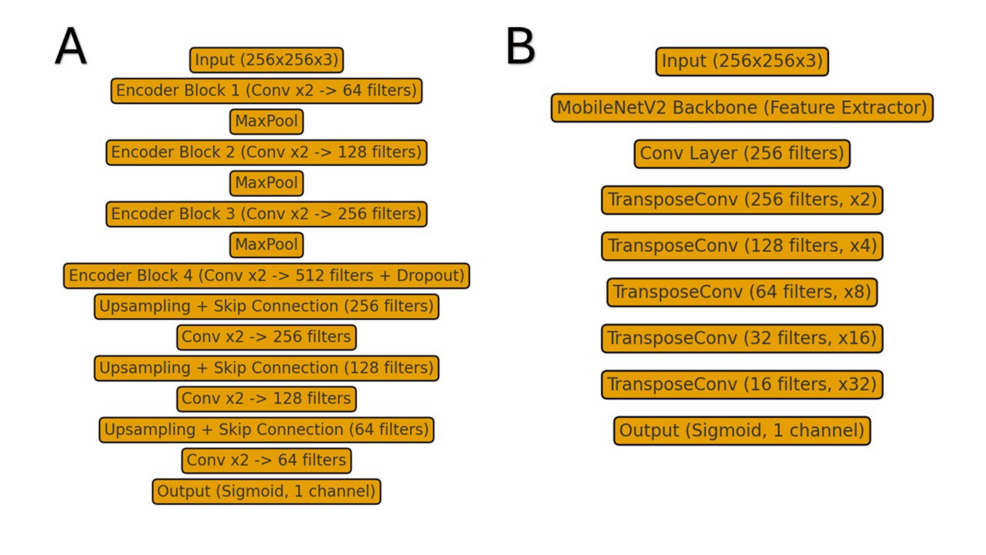

- Schematic of the experimental setup for continuous-variable entanglement-assisted quantum comumication. (Xiaolong Su et al.)

PRESS RELEASE — Entanglement-assisted quantum communication has substantial advantages in surpassing the power of classical communication by utilizing the entangled state. As a typical entanglement-assisted quantum communication encoding scheme, quantum dense coding enables two communication parties to enhance the channel capacity with the shared quantum entanglement. In continuous-variable quantum dense coding, the classical signals are encoded on both amplitude and phase quadratures of one entangled beam. Owing to the deterministic advantage in the generation and detection of continuous-variable entangled states, the combination of continuous-variable quantum dense coding enables the implementation of deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication.

Since the first experimental demonstration of quantum dense coding with entangled photon pairs, it has been experimentally demonstrated in several physical systems, including optical system, nuclear magnetic resonance system, and atomic system. However, most demonstrations of entanglement-assisted quantum communication with dense coding still remain in proof-of-principle experiments. The implementation of quantum dense coding in practical fiber channels is of great significance for advancing the practicalization of quantum communication. Therefore, it is urgent to carry out research on entanglement-assisted quantum communication with quantum dense coding in fiber channels.

In a new paper published in Light: Science & Applications, a team of scientists, led by Professor Xiaolong Su from State Key Laboratory of Quantum Optics Technologies and Devices, Institute of Opto-Electronics, Collaborative Innovation Center of Extreme Optics, Shanxi University, China and co-workers experimentally demonstrated the deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication in fiber channels. Compared to previous proof-of-principle experiments, they extended the transmission distance of deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication from meters to 20.121 km, which has potential applications in metropolitan quantum communication.

They proposed an improved continuous-variable dense coding scheme, where Alice (sender) adjusts the amplitude of the classical signals according to the transmission efficiency to ensure that the received signals can not be decoded by using the coherent state at Bob’s (receiver) station. Moreover, by transmitting entangled state and local oscillator beam independently to reduce the excess noise in the fiber channel, they experimentally demonstrated the deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication in 20-km fiber channels. They introduced the details of the experiment as follows.

“The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. At Alice’s station, the generated Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen entangled state is first coupled into the fiber. Subsequently, Alice modulates two classical signals on an ancilla coherent beam simultaneously by the fiber amplitude and phase modulators, respectively, and then couples the modulated ancilla beam and one of the entangled states on a 99:1 fiber beamsplitter to realize the encoding process. Finally, Alice transmits the entangled states to Bob through two independent fiber channels. At Bob’s station, he couples the two entangled beams on a 50:50 beam splitter. The amplitude and phase quadratures of the output beams from the 50:50 beam splitter are simultaneously measured by two homodyne detectors to realize the decoding process”.

“We encode 10 weak classical signals with different frequencies, including 5 amplitude signals and 5 phase signals, by applying the frequency division multiplexing technique as shown in Fig. 2a. With the help of the continuous-variable quantum entanglement, we successfully decode the 10 weak classical signals simultaneously, as shown in Fig. 2b and 2c. Since the correlated noises of the entangled state are lower than the corresponding shot noise limit (vacuum noise), the noise background of entanglement-assisted quantum communication is decreased, the weak classical signals that submerged in the vacuum noise are decoded, thereby the signal-to-noise ratios are increased.”

“The channel capacity of deterministic entanglement-assisted quantum communication is shown in Fig. 3. The results show that the channel capacity of entanglement-assisted quantum communication with improved signals and entanglement-assisted quantum communication is increased compared to classical communication using coherent state. The channel capacities of entanglement-assisted quantum communication based on quantum dense coding at the different transmission distances are higher than that of classical communication with coherent state in the case of large average photon number.” they added.

Continue Reading

-

Europeans shunning US as Emirates and Asia travel prove popular, says Tui | Travel & leisure

Europeans are booking fewer trips to the US, Europe’s biggest travel operator has said, as appetite for long-haul travel wanes and concerns linger around Donald Trump’s immigration policies.

Tui, which receives most of its bookings from customers in Europe, has seen “significantly lower demand” for travel into the US, according to its chief executive, Sebastian Ebel.

“What we do see is growing business to the Emirates and Asia,” he said. “We also see European demand to the Caribbean, which – due to capacity – had not been the biggest priority in the past, but there we see now potential again to grow.”

It comes amid signs that demand for long-haul travel across the Atlantic is waning.

A report by the European Travel Commission, which surveyed travellers from Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, South Korea and the US, found 42% of long-haul travellers were considering a trip to Europe this year, down from 45% last year. In the US, only 34% intended to travel to Europe, down from 37%.

In Europe, several countries have issued advisories about travel to the US owing to stricter border scrutiny, the detention of some visitors and protests over the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency.

Since Trump took office, reports have emerged from US border of tourists being detained and interrogated, people with work permits sent to ICE detention centres and people being wrongly deported.

Overseas visits to the US from western Europe were down 4% in December compared with the same month last year, according to the US National Travel and Tourism Office.

Last year, Ebel said Tui had seen a “significant decline” in travel to the US, owing to a multitude of factors including “the atmosphere, what you hear from border control”.

While demand for US holidays has been weaker, Tui hailed its best first quarter in just over a decade.

The German travel operator, which is headquartered in Hanover and employs about 67,000 people around the world, reported a 1% rise in revenue to €4.9bn (£4.3bn) in the quarter ending in December, and a 7.5% rise in operating profit to €72.9m.

Aarin Chiekrie, an analyst at the investment broker Hargreaves Lansdown, said much of the success came from its cruise business, where profits rose by more than 70%.

“Consumers continue to prioritise travel, which has seen Tui’s occupancy rates rise despite its fleet expansion,” he said. “All other business segments saw profitability improve over the period, except hotels and resorts, which suffered a double-digit decline due to losses resulting from the Jamaican hurricane, and the non-repeat of some one-off benefits last year.”

Shares in Tui, which is listed in Frankfurt, ticked up 0.4% in early trading on Tuesday. The stock has risen by about 10% in the past year.

Continue Reading

-

Fireblocks and Thales Expand Collaboration to Deliver Bank-Grade Digital Asset Security

Collaboration enables regulated institutions to deploy digital asset services using certified, customer-owned hardware within existing compliance frameworks

SINGAPORE, Feb. 10, 2026 /PRNewswire/ — Fireblocks, the enterprise platform securing more than $5 trillion in digital asset transfers annually, today announced an expanded collaboration with Thales, a global leader in cybersecurity and trusted provider of Luna Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), to deliver institutional-grade digital asset security architecture for financial institutions.

The collaboration integrates Fireblocks’ digital asset platform with Thales’ Luna HSMs, enabling institutions to extend their existing certified hardware infrastructure into digital asset operations without re-architecting security models or compromising regulatory compliance.

The architecture supports a wide range of institutional use cases, including custody, trading, tokenization, and onchain settlement, while integrating with existing security, governance, and audit processes. Organizations can securely manage cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, security tokens, and tokenized real-world assets across major blockchain networks – with support for multiple elliptic curves enabling broader cross-chain coverage and deeper liquidity.

Unlike solutions that rely on opaque security models, Fireblocks provides banks and financial institutions with complete policy control and final authority over transactions – meeting regulatory expectations for accountability and clear governance. The joint solution maps security controls directly to compliance requirements through customer-owned Luna HSMs, multi-party computation (MPC), and cross-domain integrations that regulators understand and can assess for operational risk.

This control is operationalized through Fireblocks KeyLink, which ensures private keys or key shares are generated, stored, and operated entirely within customer-owned Luna HSMs. All cryptographic operations are performed inside institution-controlled infrastructure – Fireblocks cannot unilaterally sign transactions or move assets. Instead, the platform provides policy enforcement, orchestration, and enterprise-grade governance across hot, warm, and cold operating models.

Todd Moore, Vice President, Data Security Products at Thales, commented, “As digital assets reshape global finance, adoption will depend on a proven foundation of trust. Thales provides that foundation with Luna HSMs, protecting and controlling the cryptographic keys that underpin ownership and transaction authority. Combined with Fireblocks, we help institutions reduce key-exposure risk, strengthen governance, and move digital value with confidence across high-value digital ecosystems at scale.”

“As banks and financial institutions accelerate production deployments as well as proofs-of-concept, they need digital asset infrastructure that aligns with the same governance, audit, and risk principles that underpin traditional financial infrastructure,” said Adam Levine, SVP, Head of Corporate Development and Partnerships at Fireblocks. “By expanding our partnership with Thales, we’re enabling the deployment of digital asset services using customer-owned, certified hardware they already trust – without compromising on control, compliance, or operational integrity.”

Designed to handle institutional transaction volumes at scale, Fireblocks delivers the operational resilience and continuous availability that regulators require from mission-critical financial systems. With over 95 banks already using the platform in live environments, Fireblocks enables institutional digital asset adoption grounded in proven performance, regulatory alignment, and verifiable trust.

To find out more about how to secure digital asset private keys in customer-owned certified Luna HSMs, join the webinar on 3rd March 2026: https://bit.ly/4an5zSu

About Fireblocks

Fireblocks is the world’s most trusted digital asset infrastructure company, empowering organizations of all sizes to build, manage and grow their business on the blockchain. With the industry’s most scalable and secure platform, we streamline stablecoin payments, settlement, custody, tokenization, and trading operations enabling – everything from institutional finance to consumer-facing digital experiences across the largest ecosystem of banks, payment providers, stablecoin issuers, exchanges and custodians. Thousands of organizations – including Worldpay, BNY, Galaxy, and Revolut – trust Fireblocks to secure more than $10 trillion in digital asset transactions across 150+ blockchains. Learn more at fireblocks.com

About Thales

Thales (Euronext Paris: HO) is a global leader in advanced technologies for the Defence, Aerospace, and Cyber & Digital sectors. Its portfolio of innovative products and services addresses several major challenges: sovereignty, security, sustainability and inclusion.

The Group invests more than €4 billion per year in Research & Development in key areas, particularly for critical environments, such as Artificial Intelligence, cybersecurity, quantum and cloud technologies.

Thales has more than 83,000 employees in 68 countries. In 2024, the Group generated sales of €20.6 billion.

SOURCE Fireblocks

Continue Reading

-

Oil major BP suspends buybacks in fresh sign of oil price pressure

Trowbridge in Somerset, England, on March 15, 2025.

Anna Barclay | Getty Images News | Getty Images

British oil giant BP on Tuesday posted fourth-quarter profit in line with expectations and suspended share buybacks, seeking to shore up its balance sheet as lower crude prices take their toll.

The London-listed energy firm reported underlying replacement cost profit, used as a proxy for net profit, of $1.54 billion for the final three months of 2025. That matched analyst expectations of $1.54 billion, according to an LSEG-compiled consensus.

BP’s full-year 2025 net profit came in at $7.49 billion, missing analyst expectations of $7.58 billion. That’s down from nearly $9 billion in 2024.

BP said the board decided to suspend the share buyback and fully allocate excess cash “to accelerate strengthening” of its balance sheet.

“2025 was a year of strong underlying financial results, strong operational performance, and meaningful strategic progress,” Carol Howle, BP interim chief executive officer, said in a statement.

“We have made progress against our four primary targets – growing cash flow and returns, reducing costs, and strengthening the balance sheet – but know there is more work to be done, and we are clear on the urgency to deliver,” she added.

The results come at a tough time for Europe’s oil and gas sector.

Oil prices notched their biggest annual loss since the Covid-19 pandemic last year, partly due to oversupply concerns, ratcheting up the pressure on Big Oil’s commitment to shareholder returns.

BP’s industry rivals Equinor and Shell both reported weaker quarterly earnings last week, citing lower crude prices, among other factors.

Equinor announced it would reduce share buybacks to $1.5 billion this year, down from $5 billion last year, while also trimming investments in its renewables and low-emission energy projects.

Shell, for its part, kept its buybacks steady at $3.5 billion, a move that marked the firm’s 17th consecutive quarter of $3 billion or more in buybacks.

This is breaking news. Please refresh for updates.

Continue Reading

-

Access Denied

Access Denied

You don’t have permission to access “http://www.alvarezandmarsal.com/thought-leadership/saudi-arabia-tax-alert-amendments-to-the-excise-tax-implementing-regulations-december-2025” on this server.

Reference #18.cfb31402.1770704362.41a9157b

https://errors.edgesuite.net/18.cfb31402.1770704362.41a9157b

Continue Reading

-

An agency subscription model takes shape at S4 Capital

Subscriptions were supposed to save publishers. Now, they’re becoming part of the survival logic for agencies too.

At agency holdco S4 Capital, the pivot is already taking shape.

By the end of the year, about a quarter of revenue at its Monks arm is expected to come from what it calls subscriptions — not in the Netflix sense but as a commercial model where, instead of selling hours, the agency sells ongoing access to a bundle that combines senior talent, AI workflows, agents and institutional knowledge for a steady, recurring fee.

Those agreements typically run for at least a year, with the heavy early lift of setting it all up folded into the subscription rather than billed as a one-off project, even as the tools and systems behind the work continue to improve over time.

From there, the deal works less like a fixed checklist of tasks and more like a service that gets better over time. As the AI system improves, the agency can produce more work or do it faster without having to rewrite the contract. Those efficiency gains don’t show up as fewer hours billed, they show up as more output inside the same fee.

As Monks’ co-founder and chief AI officer Wesley ter Haar put it, something that once delivered “50 of these [outputs] a month” might reach 70 as models get better and pipelines get smarter, creating ongoing value within the same commercial contract.

“With the hunger for compute about to explode do we then have to add pass through [costs], which in an ideal world, as an agency, you don’t want to do because it complicates the ability for a client to sign off on a contract if you have every variable as a pass through cost. Procurement teams hate that. So we try and wrap that up into our subscription model,” said ter Haar.

Clearly this stops well short of the outcome-based structure agency CEOs describe as the endgame. At most, subscriptions are a waypoint. The pressure behind them is more concrete. AI now handles work that used to take junior staff hours, while also introducing new, less visible costs in the form of model usage and compute. In that environment, charging by the hour fits the work less and less, pushing agencies toward models that reflect systems rather than time.

“Just like software, the subscription gets upgrades, which is why we say it’s ongoing,” said ter Haar.

Those upgrades play out across two interlocking tiers within the bundle.

On the human side, AI is absorbing more junior-heavy production, giving clients greater access to senior operators with more flexibility in how time is deployed. Hours allocated for one quarter can roll into the next, allowing the work to follow momentum rather than the calendar.

Alongside that sits the machine layer: repeatable marketing workflows powered by LLM-driven agents handling both standardized and bespoke tasks, supported by tiered knowledge bases that combine task logic, client data and broader industry intelligence. Together, these systems compress research and production time, even as most work remains under a people-in-the model rather than fully autonomous execution.

“The billable hour does not allow for any meaningful innovation, which clients understand,” said ter Haar. “They’re open to new models.”

So far one client has brought into it since last fall, and two more are expected to follow before the quarter closes.

“My goal for this year is to have about 25% of our revenue running in this model, and that is based on hopefully having three quite sizable clients signed up at the end of Q1 and then having a decent amount of new business that starts in that space,” said ter Haar.

What happens after that depends less on vision than mechanics. AI usage must remain economically manageable as tokens and inference costs fluctuate. Agencies have to decide whether to absorb or expose those tech expenses. Clients and procurement teams must accept a model that behaves differently from traditional scopes. At the same time, large legacy contracts inside organizations still built around billable hours have to unwind slowly enough for both sides to adjust. There’s also the structural risk in tying pricing too closely to raw AI consumption. The very technology meant to make work more efficiently can introduce volatility that neither side fully controls, complicating efforts to make the model feel predictable.

“Token costs are falling while usage is exploding — it’s an unstable foundation,” said Robert Webster, founder of AI marketing consultancy TAU Marketing Solutions. “It would be wrong for an agency to try to arbitrate that situation. Yes, AI usage is going to be really important as are the subsequent inference costs that it generates but I fear getting stuck in a world where large parts of the industry charge an arbitrage on tokens.”

Continue Reading

-

NTT DATA Acquires Zero&One to Accelerate Cloud Growth across the Middle East

February 10, 2026

NTT DATA, Inc.

DUBAI – 10 February 2026 – NTT DATA, a global leader in AI, digital business and technology services, has acquired Zero&One, the first homegrown Amazon Web Services (AWS) Premier Tier Services Partner in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). The acquisition significantly strengthens NTT DATA’s cloud capabilities and positions it to tap into the rapidly expanding Middle East cloud services market.

Founded in 2017 and headquartered in Dubai, Zero&One is a leading regional cloud consultancy. The company holds nine AWS competencies and was the first in the MENA to achieve AWS Generative AI Competency. In 2025, Zero&One was named AWS’s MENA Consulting Partner of the Year and received the Rising Star Partner of the Year and Design Partner of the Year awards at the EMEA level.

The acquisition supports NTT DATA’s regional growth ambitions as the Middle East cloud market enters a period of significant growth, e.g. Saudi Arabia’s cloud services market was valued at $4.77 billion last year and is expected to more than double by the early 2030s, with AWS set to open its first data center there in 2026.

“This acquisition enables us to deliver high-impact solutions and enhance the value we bring to organizations in the Middle East. Zero&One’s expertise strengthens our ability to deliver the speed, scale and technical depth clients need in today’s cloud-first environment,” said Burcak Soydan, Managing Director for the Middle East at NTT DATA.

“Joining NTT DATA is the natural next step in our growth journey,” said Ali El Kontar, CEO of Zero&One. “We’ve built our reputation on delivering world-class cloud expertise to organizations across the Middle East. As part of NTT DATA, we can now combine our regional knowledge and AWS specialization with global resources, expanded service offerings and the ability to support clients on an even larger scale. Our teams share a commitment to innovation and client success, making this an ideal partnership”

The acquisition enables NTT DATA to offer comprehensive cloud services to Middle East and African clients, including cloud migration, application modernization, cloud-native development, data analytics and AI solutions.

About NTT DATA

NTT DATA is a $30+ billion business and technology services leader, serving 75% of the Fortune Global 100. We are committed to accelerating client success and positively impacting society through responsible innovation. We are one of the world’s leading AI and digital infrastructure providers, with unmatched capabilities in enterprise-scale AI, cloud, security, connectivity, data centers and application services. Our consulting and industry solutions help organizations and society move confidently and sustainably into the digital future. As a Global Top Employer, we have experts in more than 70 countries. We also offer clients access to a robust ecosystem of innovation centers as well as established and start-up partners. NTT DATA is part of NTT Group, which invests over $3 billion each year in R&D.

Visit us at nttdata.comAbout Zero&One

Zero&One is the first homegrown AWS Premier Tier Services Partner in the MENA region, specializing in cloud-native services and solutions including application modernization, cloud operations, AI and machine learning and data analytics. Founded in 2017 and headquartered in Dubai, the company serves clients across multiple industries including financial services, retail, media and entertainment, healthcare and government. Zero&One holds nine AWS competencies and was the first in MENA to achieve AWS Generative AI Competency. For more information, visit www.zeroandone.me

Continue Reading

-

Issue of S$500 million notes by Singapore Airlines Limited: Allen & Gledhill

9 February 2026Allen & Gledhill advised Singapore Airlines Limited (“SIA”) on the issue of S$500 million notes under its S$10 billion multicurrency medium term note programme.

Advising SIA were Allen & Gledhill Partners Margaret Chin and Sunit Chhabra.

Continue Reading

-

China Hazardous Chemical Safety Compliance Management Forum (March 11) – Events – Chemicals

from CIRS

by CIRSThe Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China will take effect on May 1, 2026. This legislation comprehensively strengthens the primary responsibility of enterprises involved in hazardous chemicals, elevates compliance requirements across the entire supply chain, strictly controls licensing access, increases penalties for violations, and enhances interdepartmental regulatory coordination and enforcement collaboration. It will bring systemic and profound impacts and challenges to hazardous chemicals production and operation enterprises, as well as relevant parties such as universities and research institutions. To assist enterprises in anticipating policy trends and accurately grasping compliance essentials, the “Hazardous Chemicals Safety Compliance Management Forum” will convene in Shanghai on March 11, 2026. Hosted by the China Warehousing and Distribution Association, co-organized by the Association of International Chemical Manufacturers (AICM) and Hangzhou REACH Technology Group Co., Ltd., and undertaken by the Hazardous Materials Branch of the China Warehousing and Distribution Association.

Highlights

- Authoritative Interpretation of New National Laws and Standards with Implementation Highlights

- Latest Trends in Customs Import/Export Supervision of Hazardous Chemicals

- Practical Guidance on Hazardous Chemical Classification and Identification

- Policy Analysis and Corporate Response Strategies for the “One Enterprise, One Product, One Code” Initiative

- Latest Developments in the Revision of “GB15258 – Specifications for the Preparation of Chemical Safety Labels”

- Latest Global GHS Updates and China’s Response Recommendations

- Interpretation of Safety Technical Requirements for Storage of Hazardous Chemical Reagent Warehouses

Arrangements

- Conference Date: March 11, 2026

- Meeting Format: In-Person

- Venue: Shanghai, China (Shanghai Hongta Hotel)

- Languages: Chinese + Japanese Simultaneous Interpretation

- Hosted by: China Warehousing and Distribution Association

- Co-organizers: Association of International Chemical Manufacturers (AICM), Hangzhou REACH Technology Group Co., Ltd.

- Organized by: Dangerous Goods Branch of China Warehousing and Distribution Association

- Conference Fee: 980 RMB/person*

*Members of China Warehousing and Distribution Association and AICM enjoy a 20% discount; other enterprises registering 3 or more participants receive a 20% discount. . Fee includes materials, refreshments, and lunch. Transportation and accommodation are self-arranged.

This forum will feature

- Core drafting experts of the Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law

- Relevant officials from the General Administration of Customs and local customs authorities

- Senior experts from the Shanghai Emergency Management Affairs and Chemical Registration Center

- Senior executives from prominent chemical manufacturers and hazardous chemical storage enterprises

- Chemical Registration Center of the Ministry of Emergency Management

Agenda

Time

Agenda

Invited Guests

8:30–9:05

Registration

9:10–9:20

Opening Remarks

China Warehousing and Distribution Association, Hazardous Materials Branch

International Chemical Manufacturers Association (AICM)

Hangzhou REACH Technology Group Co., Ltd.

9:20–10:00

Interpretation of the Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law

Ma Daqing, Principal Drafting Officer of the Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law

China Academy of Work Safety

10:00-10:30

Interpretation of Customs Import/Export Supervision Trends

Chen Xiang, Head of the Dangerous Goods Section

Shanghai Customs Industrial Products and Raw Materials Testing Technology Center

10:30–10:50

Coffee Break

11:00-11:30

Technical Requirements for the Safe Storage of Hazardous Chemical Reagents

Chen Jinhe, Associate Chief Physician

Chemical Registration Center, Ministry of Emergency Management

11:30-12:00

Latest Updates on the Revision of GB15258 “Regulations for the Preparation of Chemical Safety Labels”

Chen Jun, Senior Engineer

Chemical Registration Center, Ministry of Emergency Management

12:00–12:30

Q&A

12:30–13:40

Lunch

13:40 –14:20

Hazardous Chemical Classification and Identification of Hazardous Properties

Yu Xin, Senior Engineer/Section Chief

Shanghai Emergency Management Affairs and Chemical Registration Center

14:20 –14:50

Latest “One Product, One Code” Policy for Chemicals and Response Recommendations

Zhao Dongjiao, GHS Lead, Industrial Chemistry Technology Department

CIRS Group

14:50-15:10

Coffee Break

15:10-15:50

Impact of the Hazardous Chemicals Safety Law on Chemical Storage

Lin Zhenyu, Secretary-General

Dangerous Goods Branch, China Warehousing and Distribution Association

15:50-16:20

Global GHS Regulatory Updates

Qian Zhanpeng, Manager, Industrial Chemicals Division

CIRS Group

16:20 – 17:00

Q&A

Who Shall Attend

- Members of the China Warehousing Association’s Hazardous Materials Branch, hazardous materials warehousing and logistics enterprises, and heads of chemical industrial parks nationwide

- Member companies of the Association of International Chemical Manufacturers (AICM)

- Heads of Logistics, Compliance, and Procurement Departments from Other Chemical Production, Import, and User Enterprises

- Institutions involved in hazardous materials storage facility planning and construction, logistics program directors at various academic institutions

- Suppliers of hazardous materials storage facilities and equipment (security, environmental protection, etc.)

- Heads and safety supervisors of universities, laboratories, scientific research institutions, etc.

Organizer

China Warehousing and Distribution Association

The China Warehousing and Distribution Association is a non-profit social organization registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 1997, representing the national warehousing industry. It currently operates specialized branches including joint distribution, cold chain, hazardous materials, bonded warehousing, financial warehousing, traditional Chinese medicine warehousing, technology application and engineering services, self-storage, packaging and unitized logistics, smart logistics, home logistics, and parts logistics.The association’s mission is to advance the modernization of China’s warehousing and distribution sector and promote the development of modern logistics. Guided by the principle of “grounding in warehousing, refining services, focusing on priorities, and building brands,” it concentrates on developing various warehousing facilities, expanding distribution centers, and driving innovation in warehousing, distribution services, and technology.

China Warehousing and Distribution Association Hazardous Materials Branch

The China Warehousing and Distribution Association Dangerous Goods Branch (formerly the Dangerous Goods Warehousing Branch of the China Warehousing Association) was established in Beijing on May 9, 2008, with approval from the Ministry of Civil Affairs. It is the nation’s first specialized association dedicated to dangerous goods warehousing.Its membership comprises enterprises engaged in hazardous materials warehousing, transportation, production, operation, usage, and waste disposal, as well as research institutions, educational organizations, warehouse design firms, storage equipment manufacturers, and relevant experts and scholars. It served as the primary drafting unit for the “General Rules for Storage of Hazardous Chemicals in Warehouses” (GB15603-2022).

Association of International Chemical Manufacturers (AICM)

The Association of International Chemical Manufacturers (AICM) is an international organization dedicated to advancing sustainable development in the chemical industry. Its membership includes nearly 70 multinational chemical companies with significant investments in China. Through organizing events, publishing reports, and promoting university-industry collaboration, AICM focuses on areas such as the circular economy, green manufacturing, and laboratory safety to deepen chemical companies’ commitment to social responsibility and sustainable development.

CIRS Group

CIRS Group is a global professional product safety management service provider established in 2007. Headquartered in Hangzhou, it maintains branches in Ireland,the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan, Shanghai, Beijing, and Nanjing. CIRS provides one-stop compliance solutions—ranging from regulatory consulting and laboratory testing to R&D support and data services—for chemical, cosmetic, food, medical device, disinfectant, agrochemical, and consumer goods enterprises, research institutions, and industry associations. CIRS helps companies achieve product compliance, accelerate market access, and enhance global competitiveness.

Registration and Contact

Scan the QR code below to register directly

Or add on WeChat by scanning the QR code to inquire about registration and conference details.

Email: pgl@cirs-group.com

We have launched a LinkedIn newsletter to keep you up to date on the latest developments across the chemical industry including food and FCMs and personal and home care.

Continue Reading