This study complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The analyses were conducted using aggregated, publicly available data from international repositories and previously published sources. No individual-level human or animal data were collected, and therefore, ethical approval from an institutional review board or ethics committee was not required.

Model description

We estimated the macroeconomic burden of diabetes mellitus for 204 countries. The definition of diabetes mellitus followed the GBD study’s diabetes mellitus category39. Of the 204 studied countries, data from 144 were completed for our projections. We directly calculated the macroeconomic burden of diabetes mellitus for these 144 countries using the health macroeconomic model described in detail in the previous studies15,16,17,18,19,20. In this model, diabetes mellitus affects the economy through three main pathways. First, it reduces effective labor supply through mortality and morbidity. Diabetes mellitus deaths shrink the population, including working-age individuals, while diabetes mellitus morbidity reduces productivity and increases absenteeism. We adjust labor loss using age-specific and sex-specific labor force participation rates, reducing the potential for overestimation. Second, diabetes-related treatment costs reduce aggregate savings and investment by reallocating resources from capital accumulation to healthcare consumption. While reductions in such costs may boost investment, some resources may be redirected to other diseases, slightly overstating the net economic gains. Third, we estimate only the excess informal caregiving time caused by diabetes mellitus, excluding care related to coexisting conditions. This avoids overstating the informal care burden.

We estimated the additional cost associated with the rise in diabetes mellitus cases and increased mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus attributable to COVID-19. The number of COVID-19 cases was based on daily counts of individuals infected with COVID-19, as estimated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation40. We analyzed the long-term (2020–2050) impact of infections during the first 3 years of the pandemic—1 January 2020 to 1 September 2022—according to updated COVID-19 infection projections from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. To do so, we first derived the number of additional cases of diabetes based on the increased risk of incident diabetes in COVID-19 patients; a cohort study of 181,280 participants between 1 March 2020 and 30 September 2021 found an HR of 1.40 (95% CI = 1.36–1.44) for incident diabetes in people who survived the first 30 days of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) infection relative to those who had not contracted SARS-CoV-2 (ref. 8). Then, we calculated the increased mortality rate among diabetic patients due to the increased risk of death from COVID-19 infection; a cohort study of 6,014 inpatients with diabetes—either COVID-19 positive (n = 698) or negative (n = 5,316)—revealed that diabetic patients hospitalized with COVID-19 were 3.6 times more likely to die than those not infected7. Finally, we estimated the macroeconomic cost associated with the increased mortality and morbidity of diabetes due to COVID-19. The projected long-term burden (2020–2050) reflects the elevated diabetes risk among individuals with prior COVID-19 infection from 2020 to 2022, who had a 40% higher incidence (HR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.36–1.44) compared to controls.

Providing informal or unpaid care—which constitutes a substantial proportion of diabetes mellitus care—reduces the formal labor hours of caregivers. We considered the labor impact of informal care related to diabetes mellitus by subtracting the following estimate of effective labor from the labor supply for each diabetes mellitus patient. Specifically, we assumed informal care time as 4.0 h for each diabetes patient for each week, based on the estimation provided in ref. 29, and assumed that full-time employees work an average of 35.9 h per week, as reported by the International Labour Organization41. Consequently, for each patient with diabetes mellitus, the labor supply is reduced by 0.11 (4.0 divided by 35.9) units of labor due to informal caregiving. We also considered the detailed age distribution of informal caregivers to estimate the impact of informal labor loss on the macroeconomic burden. For sensitivity analyses, we revised our estimates of weekly informal caregiving hours. We set the lower bound at 0.285 h per week, calculated by multiplying the lowest reported disability prevalence among diabetic adults (15%42) by the conservative weekly caregiving time (1.9 h per week29) for individuals with mild diabetes. The upper bound remained at 8.3 h per week29, reflecting the higher caregiving needs observed among older populations with more severe diabetes. Formal caregiving is not considered an economic loss, as it involves paid labor and generates economic value. It is treated as part of the overall economy in our accounting framework.

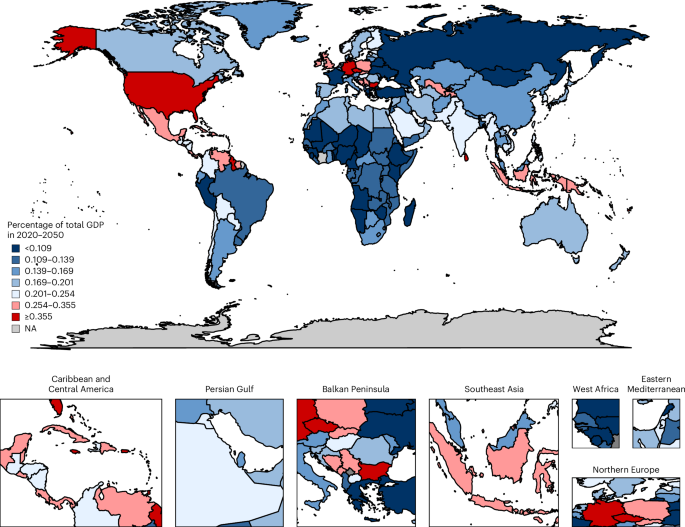

To quantify the macroeconomic burden of diabetes mellitus, we compared aggregate output (using GDP) across three scenarios over the period 2020–2050: (1) the status quo scenario, in which no interventions are implemented that could reduce the mortality, morbidity, or prevalence of diabetes mellitus relative to current and projected rates; (2) a counterfactual scenario, in which we assumed the complete elimination of diabetes mellitus at zero cost; and (3) a COVID-19 scenario, in which we estimated the increased mortality and morbidity of diabetes mellitus due to COVID-19 between 1 January 2020 and 1 September 2022. The macroeconomic burden of diabetes mellitus was calculated as the cumulative difference in projected GDP between scenarios (1) and (2), which served as the baseline. Furthermore, because COVID-19 increases the incidence of, and mortality from, diabetes mellitus, we calculated the additional macroeconomic burden attributable to COVID-19 as the cumulative difference due to the increased diabetes mellitus cases between scenarios (2) and (3) during this period. We describe our counterfactual assumptions in detail below.

In the counterfactual scenario, we assume the complete elimination of diabetes mellitus starting in 2020, consistent with the comparative risk assessment framework adopted by the GBD study. In this scenario, all diabetes-related mortality and morbidity are fully averted, while risks from other causes remain unchanged. This approach facilitates consistent cause-specific attribution of economic burden but may overestimate benefits, especially among older adults with substantial competing mortality risks. In translating this health shock into economic outcomes, our health macroeconomic model assumes that eliminating diabetes would increase the effective labor supply by reducing disease-related absenteeism, presenteeism and premature mortality. It would also reduce healthcare expenditures for diabetes treatment, thereby boosting aggregate savings and physical capital accumulation through increased investment. These health-induced changes then generate downstream effects on GDP growth over time. We do not model general equilibrium feedbacks such as changes in wages, labor force participation preferences or government budget reallocation across sectors. Instead, we apply a partial equilibrium framework with fixed labor participation rates and savings behaviors, where changes stem only from shifts in the disease burden. As such, we provide a structured yet conservative estimate of the macroeconomic burden of diabetes mellitus. These estimates are based on a simulation model and should not be interpreted as precise causal effects; rather, they are indicative projections based on clearly defined and transparent assumptions.

Data

We considered data for 204 countries and a set of World Bank regions. GDP projections for the status quo scenario, saving rates and health expenditures were taken from the World Bank’s database43,44,45. The mortality and morbidity data (years of life lost due to premature mortality and years lost due to disability) were obtained from the recently updated GBD 2021 (refs. 39,46). We relied on the International Labour Organization for age–sex-specific labor force projections47 and the Barro–Lee education database for age–sex-specific data on average years of schooling48. We obtained the age–sex-specific population from the Department of Economic and Social Affairs population dynamics database49. Using these data sources, we calculated human capital according to the Mincer equation50 and inferred the experience-related human capital component by relying on the corresponding estimates discussed in ref. 51. The physical capital data were taken from the Penn World Table projections52, and we followed standard economic estimates for the value of the output elasticity of physical capital (that is, the percentage change in output for a 1% change in the physical capital stock)53.

We used data to calculate treatment costs (ref. 38); these data include both inpatient and outpatient medical costs of diabetes mellitus. Supplementary Table 1 shows country-specific treatment data and Supplementary Table 2 shows other parameter values and data sources used in the macroeconomic model. To make country estimates comparable, all costs were converted to 2017 international dollars (2017 INT$). For 60 countries, some data—mostly on education, physical capital and the saving rate—were incomplete (see Supplementary Table 3 for details); reliable data on GDP and the prevalence rate of diabetes mellitus were available for these countries. Similar to the previous research18, we used a linear projection to approximate the economic burden of diabetes mellitus for these countries, which is shown in detail in Supplementary Table 4.

Modeling details

The goal was to calculate the economic effect of diabetes mellitus due to healthcare expenses and productivity losses from death, morbidity and informal care. For each country, we performed the following analysis:

In step 1, we identified the disease burden of diabetes mellitus (in terms of mortality, morbidity and treatment costs).

In step 2, we constructed economic projections for the following two scenarios: a status quo scenario, in which GDP is projected to grow based on current estimates and projections of disease prevalence, and a counterfactual scenario, in which diabetes mellitus prevalence is eliminated from the beginning of the time frame. The economic projections use a macroeconomic production function and can be further decomposed into the following two parts:

-

1.

Projections of effective labor supply; and

-

2.

Projections of physical capital accumulation.

In step 3, we calculated the economic loss as the cumulative difference in projected annual GDP between these two scenarios for various discount rates.

In the counterfactual scenario where diabetes mellitus is eliminated, we assume that diabetes-related morbidity and mortality are fully averted, while the risks of morbidity and mortality from other causes remain unchanged. This assumption follows the GBD comparative risk assessment framework, allowing for consistent estimation across causes. However, it may overestimate the benefits of eliminating diabetes, particularly in older populations, due to unmodeled competing risks. This detailed model description follows our previous contributions, in which we applied the framework to estimate the economic burden of noncommunicable diseases in China, Japan and South Korea15, as well as in the United States and European countries17,54, and the economic burden of noncommunicable diseases and other risk factors18.

Production function

Consider an economy in which time (t=mathrm{1,2},ldots ,infty) evolves discretely. Building upon the details in ref. 55, we considered the following production function for this economy:

$${Y}_{t}={A}_{t}{K}_{t}^{alpha }{H}_{t}^{1-alpha },$$

where ({Y}_{t}) is aggregate output; ({A}_{t}) is the technological level at time (t), which we assumed evolves exogenously; ({K}_{t}) is the physical capital stock (that is, machines, factory buildings, and so on); and ({H}_{t}) represents aggregate human capital. The parameter (alpha) is the elasticity of final output with respect to physical capital. The aggregate production function recognizes that output is not only produced with physical capital and ‘raw labor’ as in the framework discussed in ref. 56, on which the original EPIC model is based57, but with ‘effective labor’, of which health is a crucial determinant.

Physical capital evolves according to

$${K}_{t+1}=left(1-delta right){K}_{t}+{Y}_{t}-{C}_{t}-{rm{TC}}_{t}=left(1-delta right){K}_{t}+{s}_{t}{Y}_{t},$$

where (delta) refers to the depreciation rate, ({s}_{t}) refers to the saving rate, ({rm{TC}}_{t}) refers to the costs of the ongoing treatment of diabetes mellitus and ({C}_{t}) refers to the amount of consumption. From the above Equation, it follows that the saving rate is defined as

$${s}_{t}=1-frac{{C}_{t}+{rm{TC}}_{t}}{{Y}_{t}}.$$

Of note, aggregate output ({Y}_{t}) is used for the following three purposes: (1) to pay treatment costs ({rm{TC}}_{t}) (hospitalization, medication, and so on), (2) to consume the amount ({C}_{t}) and (3) to save.

Individuals of age group (a) are endowed with ({h}_{t}^{(a)}) units of human capital and supply ({{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{(a)}) units of labor from the age of 15 up to their retirement at age (R), that is, for (ain [15,R]). Children younger than 15 years of age and retirees older than (R) do not work. R varies by country and could correspond to a high age (for example, some people aged above 80 years could also be working). In the theoretical derivations, R indicates the upper bound of the summation. In our simulations, we used labor projections data from the International Labour Organization, and positive values for the labor force exist for cohorts above the age of 65 years. Aggregate human capital in the production function (1) is then defined as the sum over the age-specific effective labor supply of each age group:

$${H}_{t}=mathop{sum }limits_{a=15}^{R}{h}_{t}^{left(aright)}{{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}{n}_{t}^{left(aright)},$$

where ({n}_{t}^{a}) denotes the number of individuals in age group (a). Of note, aggregate human capital increases with the number of working-age individuals who live in the economy (that is, with a higher ({n}_{t}={sum }_{a=15}^{R}{n}_{t}^{(a)})), with individual human capital endowment (that is, with a higher ({h}_{t}^{(a)}) for at least one (a)), and with labor supply (that is, with a higher ({{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{(a)}) for at least one (a)).

We followed ref. 50 and constructed the average human capital of the cohort aged (a) according to an exponential function of education and work experience:

$${h}_{t}^{left(aright)}=exp left[{eta }_{1}left(y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}right)+{eta }_{2}left(a-y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}-5right)+{eta }_{3}{left(a-y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}-5right)}^{2}right],$$

where ({eta }_{1}) is the semi-elasticity of human capital with respect to average years of education as given by (y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}), and ({eta }_{2}) and ({eta }_{3}) are the semi-elasticities of human capital with respect to the experience of the workforce (left(a-y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}-5right)) and the experience of the workforce squared ({left(a-y{s}_{t}^{left(aright)}-5right)}^{2}), respectively. Here we assumed a school entry age of 5 years throughout.

Impact of diabetes mellitus on labor supply

Following refs. 15,17,18, the evolution of labor supply in the status quo scenario is given by

$${L}_{t}^{left(aright)}={{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}{n}_{t}^{left(aright)},mathrm{with},{n}_{t}^{left(aright)}=left[1-{sigma }_{t-1}^{left(a-1right)}right]{n}_{t-1}^{left(a-1right)},$$

where ({sigma }_{t}^{left(aright)}) is the overall mortality rate of age group (a) in time (t). Mortality and morbidity reduce effective labor supply.

Let ({sigma }_{r,t}^{left(aright)}) denote the mortality rate of people in age group (a) due to diabetes mellitus, and let ({sigma }_{-r,t}^{left(aright)}) be the overall mortality rate due to the causes other than diabetes mellitus. Then we have

$$left(1-{sigma }_{t}^{left(aright)}right)=(1-{sigma }_{r,t}^{left(aright)})(1-{sigma }_{-r,t}^{left(aright)}).$$

Mortality from diabetes mellitus reduces the labor supply by reducing the population ({n}_{t}^{left(aright)}) (through ({sigma }_{r,t}^{left(aright)})). In the counterfactual case, in which diabetes mellitus is eliminated from time (t=0) onward, the evolution of labor supply is defined similarly to the evolution of labor supply equation, but with a different overall mortality rate (({sigma }_{-r,t}^{left(aright)}) instead of ({sigma }_{t}^{left(aright)})). For simplicity, we assumed that the number of births is the same in both cases at each point in time (t).

In the counterfactual scenario, the size of the cohort aged (a) at time (t({bar{n}}_{t}^{(a)})) evolves according to

$${bar{n}}_{t}^{(a)}=left[1-{sigma }_{-r,t-1}^{left(a-1right)}right]{bar{n}}_{t-1}^{(a-1)},,{bar{n}}_{0}^{(a)}={n}_{0}^{left(aright)},,{bar{n}}_{t}^{(0)}={n}_{t}^{left(0right)},$$

Following ref. 15, the loss of labor due to mortality accumulates over the years according to

$${bar{n}}_{t}^{(a)}={n}_{t}^{left(aright)}/mathop{prod }limits_{tau =0}^{min left{t,aright}-1}left[1-{sigma }_{r,t-1-tau }^{left(a-1-tau right)}right].$$

The morbidity effect is captured by a reduction in the labor participation rate ({{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}) because people with an illness typically reduce their labor supply, either by reducing their working hours or by leaving the workforce. Following ref. 15, the labor participation rate in the counterfactual scenario ({bar{{mathcal{l}}}}_{t}^{(a)}) can be calculated as

$${bar{{mathcal{l}}}}_{t}^{(a)}approx {{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}/mathop{prod }limits_{tau =0}^{min left{t,aright}-1}left[1-{p}^{tau }{sigma }_{r,t-1-tau }^{left(a-1-tau right)}{xi }^{,left(a-1-tau right)}right],$$

where ({xi }^{,left(aright)}) measures the size of the morbidity effect relative to the relevant mortality rate, and where ({p}^{tau }) is the probability that a patient died from diabetes mellitus before time (t).

Because the impact of morbidity is hard to estimate directly, we first defined

$${xi }^{,left(aright)}=frac{mathrm{loss},mathrm{of},mathrm{labor},mathrm{due},mathrm{to},mathrm{morbidity},mathrm{in},mathrm{age},mathrm{group},a}{mathrm{loss},mathrm{of},mathrm{labor},mathrm{due},mathrm{to},mathrm{mortality},mathrm{in},mathrm{age},mathrm{group},a}.$$

Next, we assumed that the following holds in any given year for each age group (a):

$${xi }^{,left(aright)}=frac{{mathrm{YLD}}^{left(aright)}}{{mathrm{YLL}}^{left(aright)}},$$

where ({mathrm{YLD}}^{left(aright)}) represents the years lived with diabetes mellitus and ({mathrm{YLL}}^{left(aright)}) represents the years of life lost due to diabetes mellitus. Of note, ({xi }^{,left(aright)}) can be calculated from the corresponding DALY data reported by the GBD study58.

In sum, as a result of the elimination of diabetes mellitus, the ‘counterfactual scenario’ is associated with an increase in labor supply as compared with the status quo scenario. We approximated the change in labor supply (at time (t) for age group (a)) by

$$Delta {L}_{t}^{left(aright)}approx {{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}{n}_{t}^{left(aright)}mathop{sum }limits_{tau =0}^{min left{t,aright}-1}{sigma }_{r,t-1-tau }^{left(a-1-tau right)}left[1+{p}^{tau }{xi }^{,left(a-1-tau right)}right].$$

For the more general case of a partial reduction in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus by a factor (rho), we obtained the loss of labor for age group (a) at time (t) as

$$Delta {L}_{t}^{left(aright)}left(rho right)approx {{mathcal{l}}}_{t}^{left(aright)}{n}_{t}^{left(aright)}mathop{sum }limits_{tau =0}^{min left{t,aright}-1}{rho sigma }_{r,t-1-tau }^{left(a-1-tau right)}left[1+{p}^{tau }{xi }^{,left(a-1-tau right)}right].$$

The details in ref. 15 showed the mathematical proof.

For the modeling of informal care labor, we simply subtract the labor loss associated with informal care (defined as a fraction of diabetes mellitus prevalence) from the effective labor supply.

Impact of diabetes mellitus on physical capital accumulation

Diabetes mellitus also impedes the accumulation of physical capital because savings finance part of the treatment costs. Following refs. 15,17, physical capital accumulation in the counterfactual scenario can be written as

$${bar{K}}_{t+1}={bar{s}}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}+left(1-delta right){bar{K}}_{t},$$

$${bar{s}}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}={bar{I}}_{t}={bar{Y}}_{t}-{bar{C}}_{t}={{rm{s}}}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}+chi{rm{TC}}_{t},$$

where an overbar indicates the counterfactual scenario and where (chi) is the fraction of the treatment cost that is diverted to savings. The counterfactual saving rate is thus defined by

$${bar{s}}_{t}=frac{{s}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}+chi{rm{TC}}_{t}}{{bar{Y}}_{t}}.$$

For more details, see refs. 15,17.

Because diabetes mellitus is assumed to be eliminated in the counterfactual scenario, the resources that were devoted to its treatment can now be used for savings or consumption. Of note, this creates an income effect that, in reality, could affect the division of households’ income between savings and consumption. For tractability, we assumed that aggregate investment consists of two parts in the counterfactual scenario, which are as follows: a fixed share ({{rm{s}}}_{t}) of total output and an additional part from ({rm{TC}}_{t}) that would otherwise have been used to pay to treat diabetes mellitus:

$${bar{I}}_{t}={{rm{s}}}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}+chi{rm{TC}}_{t},$$

Similarly, for the case of a partial reduction in diabetes mellitus prevalence by (rho), we have

$${bar{I}}_{t}={{rm{s}}}_{t}{bar{Y}}_{t}+rho chi{rm{TC}}_{t}.$$

The intuition is that if diabetes mellitus were partially eliminated, the treatment cost that is diverted to savings should be added back proportionally.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we varied the mortality and morbidity rates. The baseline estimates were calculated with the mean mortality and morbidity data from GBD. In the sensitivity analyses, best-case and worst-case estimates were calculated based on the lower and upper bounds of GBD mortality and morbidity data. Table 1 presents the results of this sensitivity analysis in parentheses next to the baseline estimates. Second, we varied the discount rate. In the main analysis, we generated our estimates using a discount rate of 2%. We present estimates for each country by World Bank region and World Bank income group using discount rates of 0% in Supplementary Table 6 and 3% in Supplementary Table 7. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses by varying the weekly informal care hours from 0.285 to 8.3, with 4.0 as the median value (Supplementary Table 8).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.