Uzzi, B. & Spiro, J. Collaboration and creativity: the small world problem. Am. J. Sociol. 111, 447–504 (2005).

Article

Google Scholar

Uzzi, B., Mukherjee, S., Stringer, M. & Jones, B. Atypical combinations and scientific impact. Science 342, 468–472 (2013).

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Pomiechowska, B., Bródy, G., Téglás, E. & Kovács, Á. M. Early-emerging combinatorial thought: human infants flexibly combine kind and quantity concepts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2315149121 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Frank, M. R. et al. Toward understanding the impact of artificial intelligence on labor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6531–6539 (2019).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Grossmann, I. et al. AI and the transformation of social science research. Science 380, 1108–1109 (2023).

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Shirado, H. & Christakis, N. A. Locally noisy autonomous agents improve global human coordination in network experiments. Nature 545, 370–374 (2017).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Shin, M., Kim, J., van Opheusden, B. & Griffiths, T. L. Superhuman artificial intelligence can improve human decision-making by increasing novelty. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2214840120 (2023).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Rahman, H. A. The invisible cage: workers’ reactivity to opaque algorithmic evaluations. Adm. Sci. Q. 66, 945–988 (2021).

Article

Google Scholar

Guilford, J. P. The Nature of Human Intelligence (McGraw-Hill, 1967).

Stevenson, C., Smal, I., Baas, M., Grasman, R. & van der Maas, H. Putting GPT-3’s creativity to the (alternative uses) test. In Proc. 13th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC’22) (eds Hedblom, M. M. et al.) 164–168 (Association for Computational Creativity, 2022).

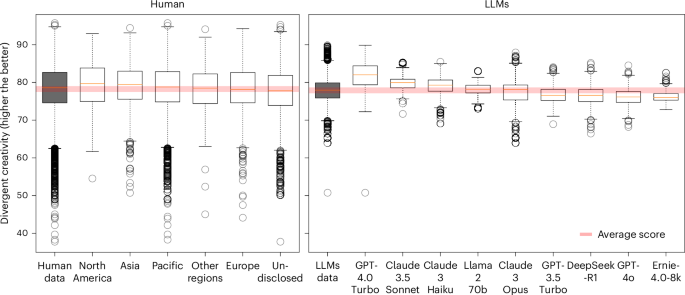

Haase, J. & Hanel, P. H. P. Artificial muses: generative artificial intelligence chatbots have risen to human-level creativity. J. Creat. 33, 100066 (2023).

Article

Google Scholar

Chakrabarty, T., Laban, P., Agarwal, D., Muresan, S. & Wu, C.-S. Art or artifice? Large language models and the false promise of creativity. In Proc. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024); https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3642731

Tian, Y. et al. MacGyver: are large language models creative problem solvers? In Proc. 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (eds Duh, K. et al.) (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024); https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.naacl-long.297

Doshi, A. R. & Hauser, O. P. Generative AI enhances individual creativity but reduces the collective diversity of novel content. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn5290 (2024).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Guo, D. et al. DeepSeek-R1 incentivizes reasoning in LLMs through reinforcement learning. Nature 645, 633–638 (2025).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Jia, N., Luo, X., Fang, Z. & Liao, C. When and how artificial intelligence augments employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 67, 5–32 (2024).

Article

Google Scholar

van den Broek, E., Sergeeva, A. & Huysman, M. When the machine meets the expert: an ethnography of developing AI for hiring. MIS Q. 45, 1557–1580 (2021).

Article

Google Scholar

Olson, J. A., Nahas, J., Chmoulevitch, D., Cropper, S. J. & Webb, M. E. Naming unrelated words predicts creativity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022340118 (2021).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Bao, L., Cao, J., Gangadharan, L., Huang, D. & Lin, C. Effects of lockdowns in shaping socioeconomic behaviors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2405934121 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Beketayev, K. & Runco, M. A. Scoring divergent thinking tests by computer with a semantics-based algorithm. Eur. J. Psychol. 12, 210–220 (2016).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Brophy, D. R. Understanding, measuring, and enhancing individual creative problem-solving efforts. Creat. Res. J. 11, 123–150 (1998).

Article

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. The social psychology of creativity: a componential conceptualization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45, 357–376 (1983).

Article

Google Scholar

Long, H. & Pang, W. Rater effects in creativity assessment: a mixed methods investigation. Think. Skills Creat. 15, 13–25 (2015).

Article

Google Scholar

Dumas, D., Organisciak, P. & Doherty, M. Measuring divergent thinking originality with human raters and text-mining models: a psychometric comparison of methods. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000319. (2020).

Beaty, R. E., Johnson, D. R., Zeitlen, D. C. & Forthmann, B. Semantic distance and the alternate uses task: recommendations for reliable automated assessment of originality. Creat. Res. J. 34, 245–260 (2022).

Article

Google Scholar

Guilford, J. P. Creativity: yesterday, today and tomorrow. J. Creat. Behav. 1, 3–14 (1967).

Article

Google Scholar

Wallach, M. A. & Kogan, N. A new look at the creativity-intelligence distinction. J. Pers. 33, 348–369 (1965).

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Yang, Y., Youyou, W. & Uzzi, B. Estimating the deep replicability of scientific findings using human and artificial intelligence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 10762–10768 (2020).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Farquhar, S., Kossen, J., Kuhn, L. & Gal, Y. Detecting hallucinations in large language models using semantic entropy. Nature 630, 625–630 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Pividori, M. Chatbots in science: what can ChatGPT do for you? Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02630-z (2024).

Samdarshi, P. et al. Connecting the dots: evaluating abstract reasoning capabilities of LLMs using the New York Times Connections word game. In Proc. 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds Al-Onaizan, Y. et al.) (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024); https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.1182

Todd, G., Merino, T., Earle, S. & Togelius, J. Missed connections: lateral thinking puzzles for large language models. In Proc. 2024 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG) 1–8 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2024).

Cvrček, V. et al. Comparing web-crawled and traditional corpora. Lang. Resour. Eval. 54, 713–745 (2020).

Article

Google Scholar

Horowitz, J. L. Bootstrap methods in econometrics. Annu. Rev. Econ. 11, 193–224 (2019).

Article

Google Scholar

Efron, B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 7, 1–26 (1979).

Article

Google Scholar

Jentzsch, S. & Kersting, K. ChatGPT is fun, but it is not funny! Humor is still challenging large language models. In Proc. 13th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment, & Social Media Analysis (eds Barnes, J. et al.) 325–340 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

Castillo, L., León-Villagrá, P., Chater, N. & Sanborn, A. Explaining the flaws in human random generation as local sampling with momentum. PLoS Comput. Biol. 20, e1011739 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Angelike, T. & Musch, J. A comparative evaluation of measures to assess randomness in human-generated sequences. Behav. Res. Methods 56, 7831–7848 (2024).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Geva, E. & Ryan, E. Linguistic and cognitive correlates of academic skills in first and second languages. Lang. Learn. 43, 5–42 (1993).

Article

Google Scholar

Henrickson, L. & Meroño-Peñuela, A. Prompting meaning: a hermeneutic approach to optimising prompt engineering with ChatGPT. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01752-8 (2023).

Giray, L. Prompt engineering with ChatGPT: a guide for academic writers. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 51, 2629–2633 (2023).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Lin, Z. How to write effective prompts for large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 611–615 (2024).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Aggarwal, A., Lohia, P., Nagar, S., Dey, K. & Saha, D. Black box fairness testing of machine learning models. In Proc. 2019 27th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (Association for Computing Machinery, 2019); https://doi.org/10.1145/3338906.3338937

Chao, P. et al. Jailbreaking black box large language models in twenty queries. In Proc. 2025 IEEE Conference on Secure and Trustworthy Machine Learning (SaTML) 23–42 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2025).

Lapid, R., Langberg, R., & Sipper, M. Open sesame! Universal black-box jailbreaking of large language models. Appl. Sci. 14, 7150 (2024).

Article

CAS

Google Scholar

Chesebrough, C., Chrysikou, E. G., Holyoak, K. J., Zhang, F. & Kounios, J. Conceptual change induced by analogical reasoning sparks aha moments. Creat. Res. J. 35, 499–521 (2023).

Article

Google Scholar

Beaty, R. E. & Kenett, Y. N. Associative thinking at the core of creativity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 27, 671–683 (2023).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Te’eni, D. et al. Reciprocal human-machine learning: a theory and an instantiation for the case of message classification. Manage. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.03518 (2023).

Yax, N., Anlló, H. & Palminteri, S. Studying and improving reasoning in humans and machines. Commun. Psychol. 2, 51 (2024).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Strachan, J. W. A. et al. Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1285–1295 (2024).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Bzdok, D. et al. Data science opportunities of large language models for neuroscience and biomedicine. Neuron 112, 698–717 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

Google Scholar

Padmakumar, V. & He, H. Does writing with language models reduce content diversity? In Proc. International Conference on Representation Learning (Kim, B. et al.) 642–669 (ICLR, 2024).

Anderson, B. R., Shah, J. H. & Kreminski, M. Homogenization effects of large language models on human creative ideation. In Proc. 16th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Association for Computing Machinery, 2024); https://doi.org/10.1145/3635636.3656204

Mohammadi, B. Creativity has left the chat: the price of debiasing language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05587 (2024).

Groh, M. et al. Deep learning-aided decision support for diagnosis of skin disease across skin tones. Nat. Med. 30, 573–583 (2024).

Article

CAS

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Marks, M. A., DeChurch, L. A., Mathieu, J. E., Panzer, F. J. & Alonso, A. Teamwork in multiteam systems. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 964–971 (2005).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Vaccaro, M., Almaatouq, A. & Malone, T. When combinations of humans and AI are useful: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 2293–2303 (2024).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Bellemare-Pepin, A. et al. Divergent creativity in humans and large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.13012 (2024).

Chen, H. & Ding, N. Probing the ‘creativity’ of large language models: can models produce divergent semantic association? In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023 (eds Bouamor, H. et al.) (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023); https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.findings-emnlp.858

Childs, P. et al. The creativity diamond—a framework to aid creativity. J. Intell. 10, 73 (2022).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Chen, L. et al. TRIZ-GPT: an LLM-augmented method for problem-solving. In Proc. 36th International Conference on Design Theory and Methodology (DTM) V006T06A010 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2024).

Chen, L. et al. DesignFusion: integrating generative models for conceptual design enrichment. J. Mech. Des. 146, 111703 (2024).

Article

Google Scholar

Hennessey, B. A., Amabile, T. M. & Mueller, J. S. in Encyclopedia of Creativity (Elsevier, 2011); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375038-9.00046-7

Cropley, A. In praise of convergent thinking. Creat. Res. J. 18, 391–404 (2006).

Article

Google Scholar

Wang, D. Presentation in self-posted facial images can expose sexual orientation: Implications for research and privacy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 122, 806–824 (2022).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Taylor, J. E. T. & Taylor, G. W. Artificial cognition: how experimental psychology can help generate explainable artificial intelligence. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 28, 454–475 (2021).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar

Voudouris, K. et al. Direct human–AI comparison in the animal–AI environment. Front. Psychol. 13, 711821 (2022).

Article

PubMed

PubMed Central

Google Scholar

Hitsuwari, J., Ueda, Y., Yun, W. & Nomura, M. Does human–AI collaboration lead to more creative art? Aesthetic evaluation of human-made and AI-generated haiku poetry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 139, 107502 (2022).

Article

Google Scholar

Griffiths, T. L. Understanding human intelligence through human limitations. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 873–883 (2020).

Article

PubMed

Google Scholar