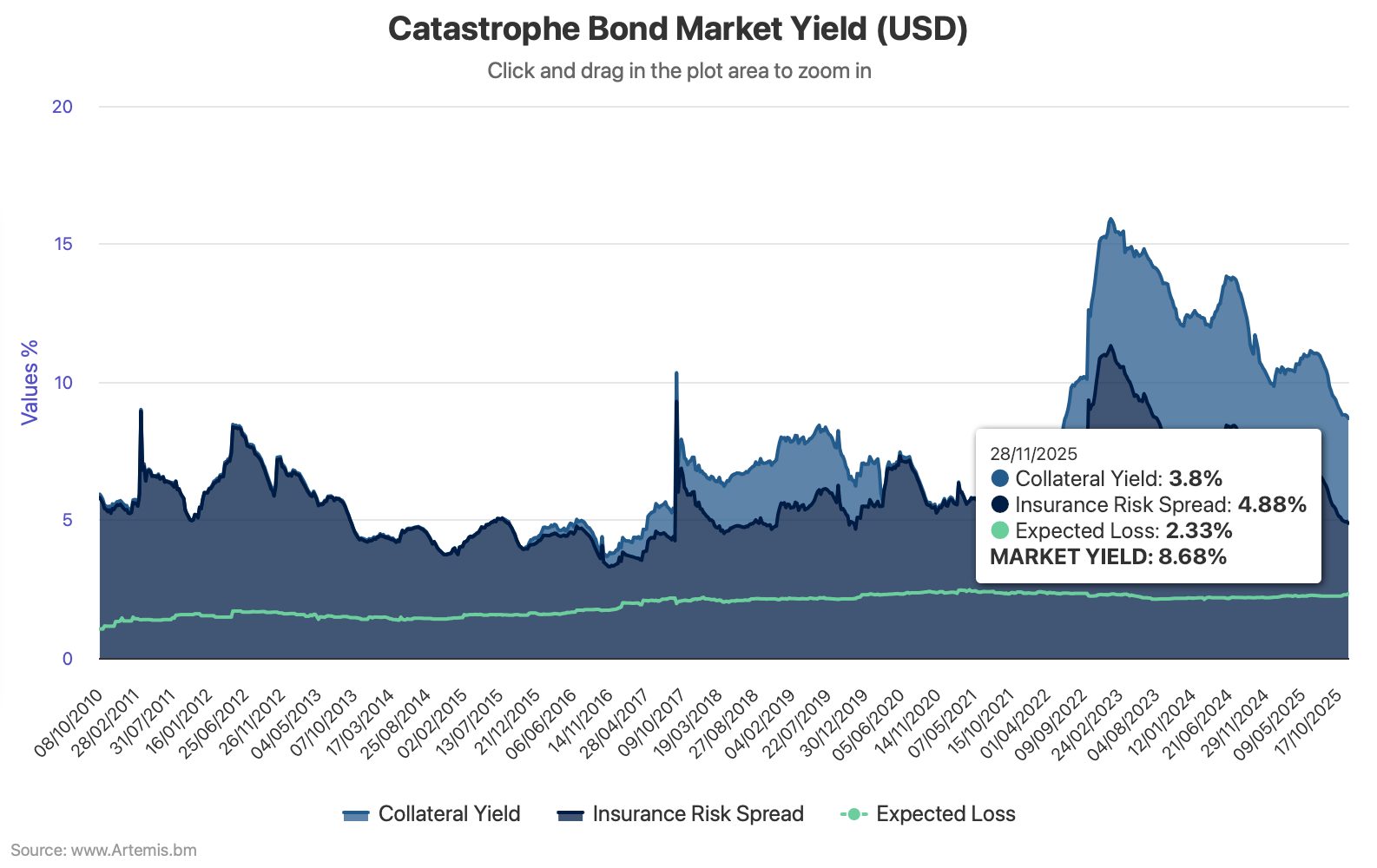

The overall yield of the catastrophe bond market, or the total coupon return, fell to just under 8.70% as of November 28th 2025, but the decline in the cat bond market insurance risk spread, or discount margin, was slower in the last month, the latest data from Plenum Investments shows.

With the seasonal spread tightening caused by the Atlantic hurricane season all but over in November, the main contributing factor to the decline continued to be the elevated levels of investor demand for catastrophe bond investments, as well as the excess cash in the market from returns earned by cat bond fund strategies, it appears.

This was despite high and growing demand for reinsurance coverage from the catastrophe bond market, as issuance was continuing to build and demand remained in excess of the pipeline for most of November.

But, with the pipeline of new cat bond issuance still increasing, there are hopes the market may become more balanced and spreads level off, while seasonality related to the hurricane season is now over.

Supply-demand factors, related to the cat bond market evidently experiencing a high supply of capital in part due to returns generated by funds, as well as high demand for new investments over recent weeks, is continuing to apply pressure though.

The overall yield of the catastrophe bond market had sat at 11.03% at the end of June 2025, then declined to 10.81% by August 1st, then 10.22% as of August 29th and further still to 9.43% as of September 26th, then fell to 8.81% by the end of October.

The further decline to roughly 8.69% as of November 28th 2025 therefore represents a meaningful slowing of the decline in cat bond risk spreads across the market.

You can analyse the yield of the catastrophe bond market over time in our interactive chart, which uses data kindly shared by Plenum Investments.

Commenting on developments in the cat bond market coupon over the last month, Plenum Investments explained, “In November, reinsurance premiums continued to decline despite high demand for insurance coverage. However, the rate of decline compared to the previous month has noticeably slowed down.

“The decrease in yields is expected to further moderate, as we anticipate that the CAT bond supply will remain high and the seasonal effect will reverse after the hurricane season.”

Plenum Investments also noted that secondary trading has also begun to increase further in the cat bond market, contributing towards a more balanced relationship between supply and demand as primary issuance is rising again at a pace sufficient to satisfy more of the capacity that has been available.

The insurance risk spread, or discount margin of the catastrophe bond market, having declined to 5.48% at September 26th 2025, then 4.99% at October 31st 2025, fell further to 4.88% at November 28th 2025.

The risk-free return on collateral remained relatively stable, only reducing slightly from 3.82% at October 31st to 3.80% at November 28th.

However, the expected loss of the cat bond market as measured using Plenum Investment’s methodology rose from 2.25% at October 31st to stand at 2.33% at November 28th 2025, presumably with recent issues driving that increase in the main.

Which means one of the metrics worth tracking in the catastrophe bond market, of the amount of risk spread available over the expected loss, has now narrowed to only 2.56% when rounded up.

That is down more than a percentage point since the end of November 2024 and the average spread above expected loss of the cat bond market, by Plenum’s data, has now sunk to a level that hasn’t been seen since November 15th 2019.

At 4.88%, the average insurance risk spread of the cat bond market, the discount margin, has now declined by 16% in the last year and stands roughly 27% lower than two years ago.

If you compare the average risk spread of today with the one the market experienced at the end of November 2022, bearing in mind that is when spreads spiked higher after hurricane Ian, the decline over the last three years is now approximately 55%.

All of which serves to demonstrate how cyclical the catastrophe bond market is, but also how it responds to both threats such as hurricane Ian that spiked risk spreads higher, and then to capital availability as we see today after the strong years of elevated returns that have been experienced.

Analyse catastrophe bond market yields over time using this chart.