Family Fun Day is all about bringing the joy of tennis and entertainment to every corner of the precinct. Whether you’re cheering courtside or exploring the grounds, there’s something for everyone!

…

Family Fun Day is all about bringing the joy of tennis and entertainment to every corner of the precinct. Whether you’re cheering courtside or exploring the grounds, there’s something for everyone!

…

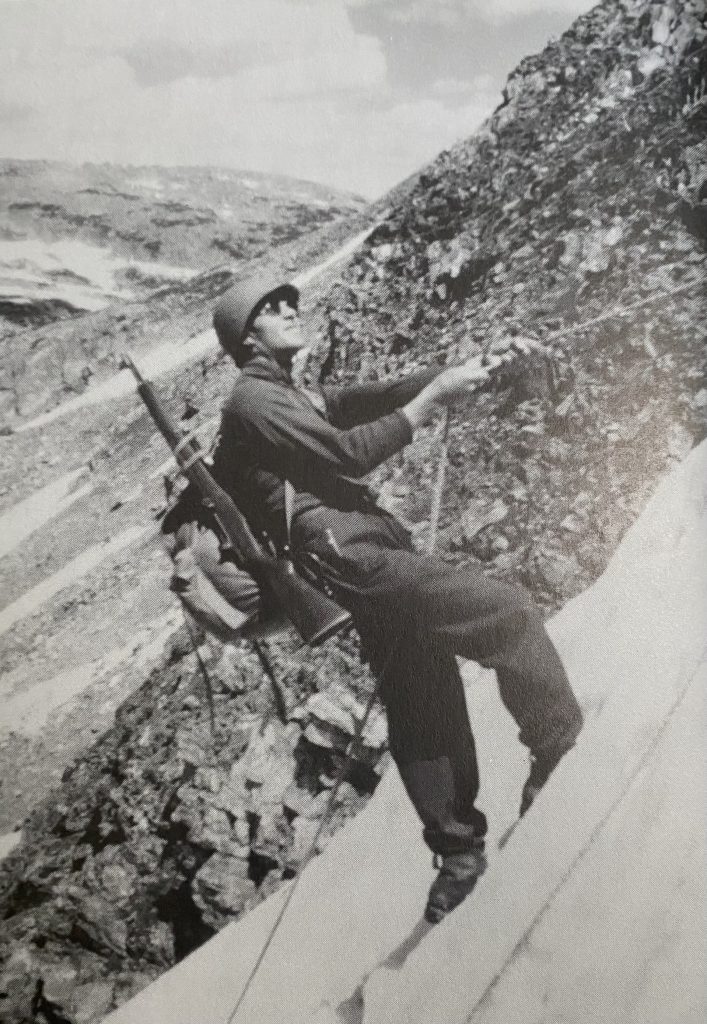

Vail-area filmmaker Chris Anthony has completed his latest work, a biopic of 10th Mountain Division veteran and Aspen Ski Corp. co-founder Friedl…

A cause of death has not been determined, and foul play is reportedly not suspected

Victoria Jones, the daughter of actor Tommy Lee Jones, was found dead…

I have a little over an hour before my next activity. The afternoon sun is beating down on my skin, beads are quickly forming on my G&T and Stevie Nicks’s Edge of Seventeen is playing through the speakers. A pair of curious monkeys are eyeing…

Taylor Swift rang in the New Year in style while celebrating her close friend Este Haim’s wedding in California.

The pop superstar attended the New…

Family Fun Day is all about bringing the joy of tennis and entertainment to every corner of the precinct. Whether you’re cheering courtside or exploring the grounds, there’s something for everyone!

…

SAN ANTONIO – One man is dead after a shooting Thursday…

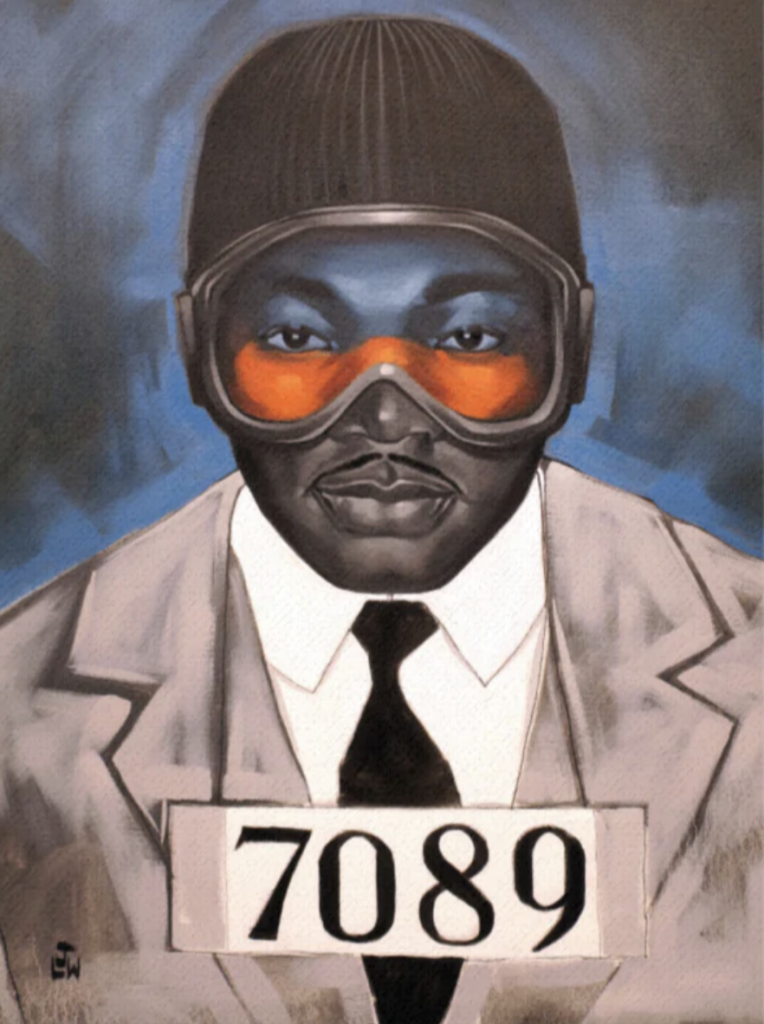

As winter settles into the Yampa Valley and the new year begins, Steamboat Springs will once again turn downtown into a walking gallery during First Friday ArtWalk on Friday, Jan. 2. This month features a range of works across various mediums…

Any show with “Run” as its title surely ought to bolt out of the gates and fang it hell-for-leather – barely stopping to catch its breath, proverbial sirens wailing. So it was a touch disappointing to discover that this new six-part series…