Published: 15 December 2025

Their testimonies guide every beat of the series. It’s not about…

Published: 15 December 2025

Their testimonies guide every beat of the series. It’s not about…

Tracy Letts’s 1996 thriller play deals in conspiracy, delusion, and infestation, but it’s also about the unlikely connection and trust between two troubled people.

Bug is a play built to creep under your skin. With its talk of conspiracies,…

Global superstar Mariah Carey is the first major international guest who will be among the leading performers at the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Winter Games Milano Cortina 2026.

The five-time Grammy award winning artist, recognised…

The City of Johannesburg, through the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), hosted the Sugar Coats exhibition by acclaimed Zimbabwean artist Gresham Tapiwa Nyaunde on Saturday, 13 December 2025.

Nyaunde is the 2024 FNB Art Prize winner, and…

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor may have taken his exit from the royal fold rather well, but he is seemingly unsettled about the fate of his bedroom…

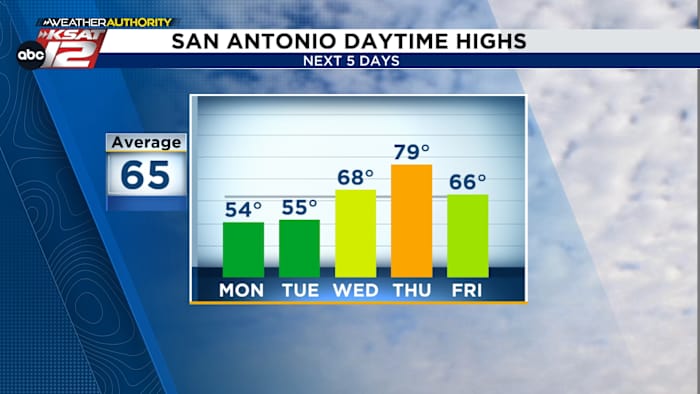

SA STAYS JUST ABOVE FREEZING: Most of Bexar County stays above the freezing mark this morning

MOSTLY CLOUDY & COOL TODAY: Few peeks of sun, highs in the 50s

SMALL RAIN CHANCE TUESDAY: Light showers possible Tuesday afternoon…

As founder and artistic director of Quantum Theatre, Karla Boos changed the face of Pittsburgh stage scene with ambitious, often experimental productions, each of which took place in a new location,…

Date: 15 December 2025

Category: City regeneration and development

‘Vacant to Vibrant Citywide’ has proved…

Winter Walk

She left the hut and bright log fire at noon

And walked outside on crisp white winter snow

To find the iced slopes shadowed like the moon,

The wild wood desolate and bare below;

The red trees wet, adrift with icy flow,

The evergreens with…