With kick-off underway, Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, Calif. is packed with fans repping the Seahawks and the Patriots at Super Bowl XL.

Jay-Z, Blue Ivy Carter, Jon Bon Jovi, Travis Kelce, Travis Scott and more were present to watch…

With kick-off underway, Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, Calif. is packed with fans repping the Seahawks and the Patriots at Super Bowl XL.

Jay-Z, Blue Ivy Carter, Jon Bon Jovi, Travis Kelce, Travis Scott and more were present to watch…

One of the most coveted pieces of Super Bowl merch this year won’t be sold in stores, and the NFL probably doesn’t want to see it in the stands.

It’s a rally towel with a cute, punting bunny graphic from acclaimed L.A. illustrator Lalo…

The players for the Seattle Seahawks and the New England Patriots weren’t the only stars in Santa Clara, California, for Super Bowl LX on Sunday.

Many Hollywood notables and celebrities were among the thousands packed inside Levi’s…

Halle Berry and Chris Hemsworth appear to have formed a strong bond while working…

American actress, choreographer, dancer, Kennedy Center Honoree and fashion swan, Carmen de Lavallade was, as WWD wrote in 1983, “very beautiful.” The New Orleans native and first Black prima ballerina at the Metropolitan Opera was a…

Royal family’s approach to dealing with former Prince Andrew has finally been revealed…

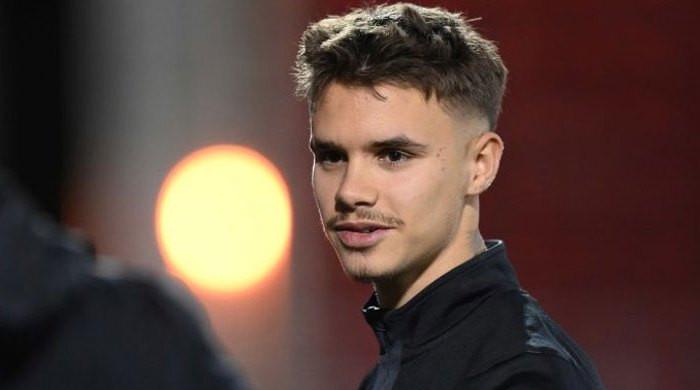

Romeo Beckham has drawn attention for a very personal gesture, unveiling a new “Family” tattoo at a time when tensions within the Beckham…

Kendall JennerPhoto by: Sophie Sahara

Michael Rubin’s Fanatics Super Bowl Party was the it invite this weekend ahead of the game. The annual, late afternoon bash was once again jam-packed with famous faces—including Jay-Z, Kendall Jenner,…

At tables across the room, guests included Lake Bell, Chloe Bailey, Ryan Destiny, Emma Grede, Arya Starr, Quenlin Blackwell, Sloane Stephens, Olandria Carthen, and Winnie Harlow. Once Grede, chairwoman of the Fifteen Percent Pledge, pointed out…