National Geographic’s new documentary, “Chris Hemsworth: A Road Trip to Remember,” opens with the “Thor” actor reflecting on a cherished childhood photo with his father in the Australian Outback.

In the image, Hemsworth’s dad, Craig…

National Geographic’s new documentary, “Chris Hemsworth: A Road Trip to Remember,” opens with the “Thor” actor reflecting on a cherished childhood photo with his father in the Australian Outback.

In the image, Hemsworth’s dad, Craig…

Taipei, Nov. 24 (CNA) The three upcoming concerts in Taipei by Taiwanese pop diva Jolin Tsai (蔡依林) are all sold out, with the tickets snapped up shortly after they went on sale at noon Sunday, according to her talent agency.

Some 940,000…

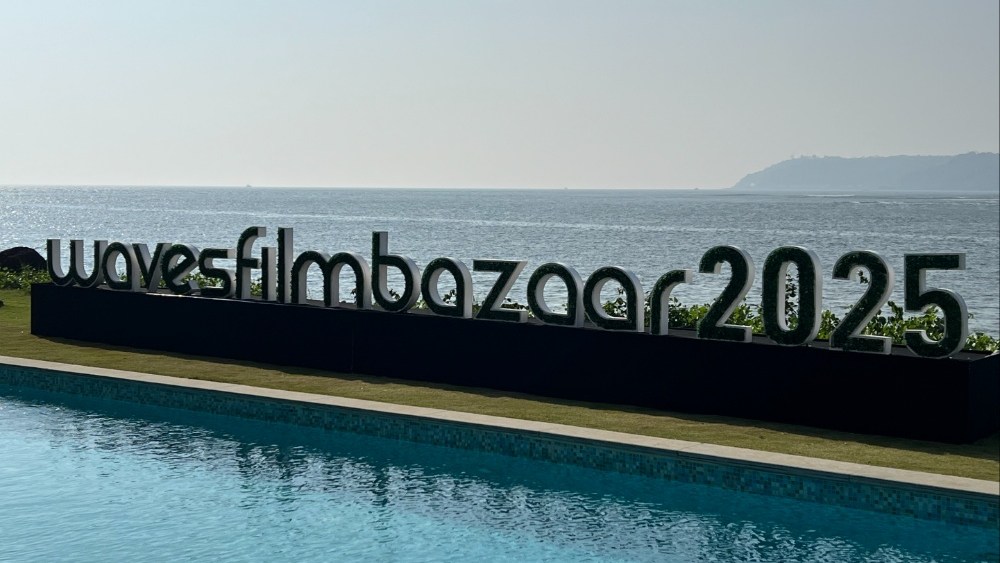

Kiran Rao‘s production banner Kindling Pictures is backing commercial director Bosco Bhandarkar’s feature directorial debut “Shadow Hill: Of Spirits and Men,” which has been selected for the WAVES Film Bazaar‘s Co-Production…

SPOILER ALERT: This story contains spoilers from Season 1, Episode 5 of “It: Welcome to Derry,” now streaming on HBO Max.

Pennywise the Clown feeds on fear, and children are his entree of choice.

When the first episode of HBO’s…

Two new awards, UNESCO Creative Cities Network City of Film Award for the Best Co-Production Market Project and the Matchbox Gap Award for the Best Film Bazaar Recommends Project, have been unveiled at WAVES Film Bazaar, the market component…

Immigrant drama “Feather Men” (Khoriya), the debut feature from Delhi-based filmmaker Vishwendra Singh, has been selected for the Work-in-Progress (WIP) section at WAVES Film Bazaar, the market component of the International…

Set within the charged social landscape of Ahmedabad, writer-director Aarti Neharsh’s debut feature “Kanda” or “No Onions” uses psychological horror to probe questions of purity, caste and domestic control.

The film has Shakun…

Rebel Wilson is speaking out about the multi-pronged legal proceedings that have marred her directorial debut, the comedy musical The Deb, by controversy.

In a new segment with 60 Minutes Australia, Wilson dubbed the experience her…