- FAST reveals insights into cosmic signals Dawn

- HKU Astronomer Uses ‘China Sky Eye’ To Reveal Binary Origin Of Fast Radio Bursts Eurasia Review

- China’s giant radio telescope cracks code on origin of cosmic radio bursts news.cgtn.com

Category: 7. Science

-

FAST reveals insights into cosmic signals – Dawn

-

China’s satellite data shows iceberg A23a in final stage of disintegration

BEIJING — China”s Fengyun-3D satellite has found that the world’s formerly largest iceberg, A23a, is entering the final stages of its disintegration, according to the China Meteorological Administration.

True-color…

Continue Reading

-

A23a, once world's largest iceberg, could disappear within weeks – news.cgtn.com

- A23a, once world’s largest iceberg, could disappear within weeks news.cgtn.com

- Massive iconic iceberg turns blue and is “on the verge of complete disintegration,” NASA says CBS News

- Earth from Space: The fate of a giant European Space Agency

Continue Reading

-

The World’s Longest-Running Lab Experiment Is Almost 100 Years Old : ScienceAlert

Sometimes science can be painfully slow. Data comes in dribs and drabs, truth trickles, and veracity proves viscous.

The world’s longest-running lab experiment is an ongoing work in sheer scientific patience. It has been running continuously…

Continue Reading

-

SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launches 29 Starlink satellites to orbit from Florida

Another Starlink launch is now in the record books.

SpaceX on Sunday (Jan. 18) sent a new batch of 29 Starlink satellites (Group 6-100) into low Earth orbit. At 6:31 p.m. EDT (2331 GMT), the company launched a Falcon 9 rocket from Complex 40 at…

Continue Reading

-

Study shows why trees don’t grow faster when CO2 levels are high

Plants absorb carbon dioxide and water, use sunlight to make sugars, and release oxygen. So if the air contains more CO₂, shouldn’t forests grow faster, store more carbon, and help cool the planet?

It’s plausible and often repeated, but it…

Continue Reading

-

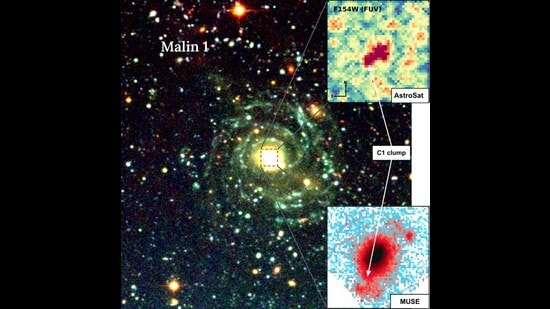

Malin 1’s secret diet: Giant galaxy found quietly cannibalising smaller neighbours

Astronomers have uncovered hidden evidence that Malin 1, the largest known low-surface-brightness galaxy in the universe, is quietly growing by swallowing smaller dwarf galaxies, a process that had remained invisible until now.

One clump, named… Continue Reading

-

Toxic gas wiped out half of all ocean life 530 million years ago

About 530 million years ago, during the early rise of complex animal life, a massive marine die-off erased roughly 45% of ocean species.

Sediment cores from the Yangtze Platform in South China point to hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas produced in

Continue Reading

-

Ashwagandha aids recovery without blunting training stress in athletes

A controlled trial in team-sport athletes suggests Ashwagandha may help maintain hormonal balance and support recovery and power adaptations during the physiological strain of pre-season training.

Study: Ashwagandha Root Extract…

Continue Reading

-

Time-lapse of radar images shows how the Antarctic ice shelf collapses – MSN

- Time-lapse of radar images shows how the Antarctic ice shelf collapses MSN

- Watch This Glacier Race into the Sea Nautilus | Science Connected

- Experts Tracked How Fast Greenland and Antarctica’s Ice Is Moving — the Numbers Are Alarming Green…

Continue Reading