After 167 days in space, the crew members of NASA’s SpaceX Crew-11 mission will hold a news conference at 2:15 p.m. EST, Wednesday, Jan. 21, at the agency’s Johnson Space Center in Houston to discuss their science expedition aboard the…

Category: 7. Science

-

NASA says its Crew-11 astronauts have arrived in Houston after 1st-ever medical evacuation from space station – Space

- NASA says its Crew-11 astronauts have arrived in Houston after 1st-ever medical evacuation from space station Space

- Astronauts return to Earth after first ever medical evacuation from space station BBC

- NASA, in a rare move, cuts space station…

Continue Reading

-

A Simulated Asteroid Impact Reveals the Strength of Iron-Rich Rocks

Around the sun, there are countless small bodies whose orbits occasionally bring them in close proximity to Earth, known as Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). There are currently 37,000 known Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) and 120 known…

Continue Reading

-

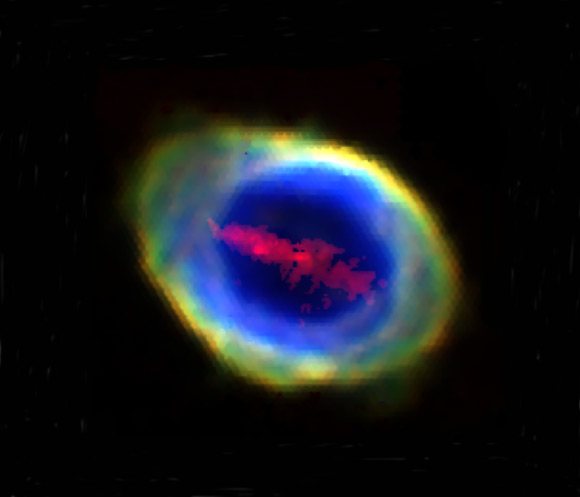

Astronomers Spot Surprising Iron ‘Bar’ at Heart of Ring Nebula

Astronomers using the WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer (WEAVE), a powerful new instrument mounted on the William Herschel Telescope on La Palma, have detected an unexpected, elongated structure of ionized iron inside the famous Ring…

Continue Reading

-

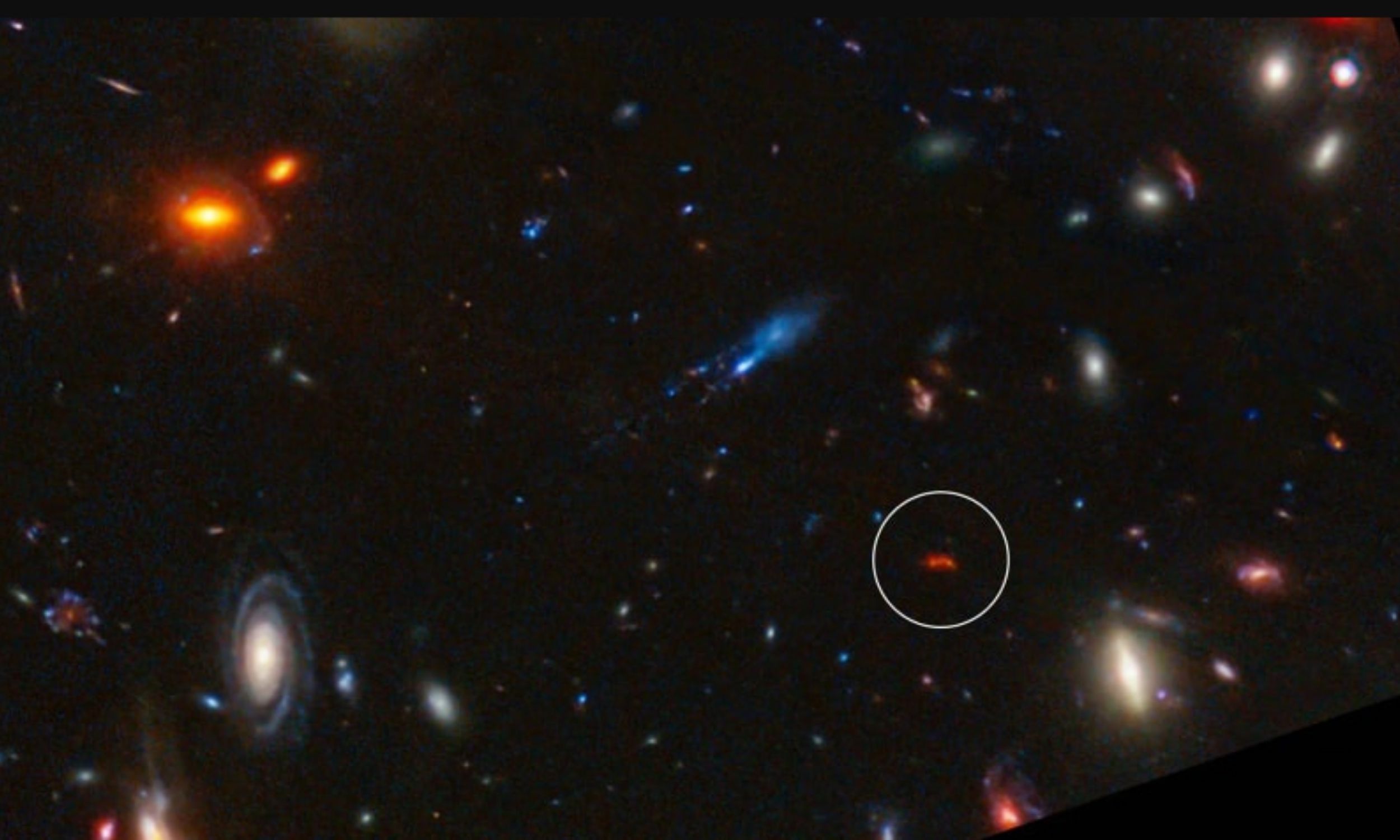

Superheated young galaxy Y1 formed stars at a record pace

A distant early-universe galaxy is turning out more than 180 solar masses of new stars each year, based on a temperature reading from a Chilean telescope analysis. Known as galaxy Y1, this ultraluminous infrared “star factory” is wrapped in…

Continue Reading

-

Kidney Glomerulus-on-a-Chip Advances Severe Kidney Disease Treatment

Study in a Sentence: Translational medicine researchers used the Mimetas® human kidney glomerulus-on-a-chip to investigate potential pharmaceutical interventions for patients with a severe kidney disease called focal segmental glomerulosclerosis…

Continue Reading

-

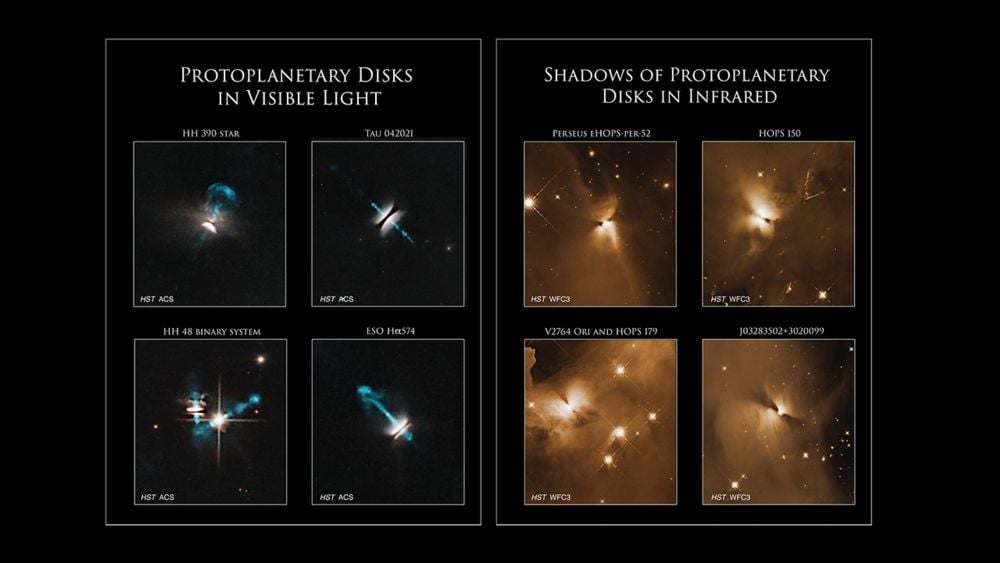

Exploring Where Planets Form With The Hubble Space Telescope

When the Hubble Space Telescope began operations 35 years ago, it was motivated by some ambitious science goals. From its position in Low-Earth Orbit (LEO), the Hubble was poised to address fundamental questions in astronomy. It was…

Continue Reading

-

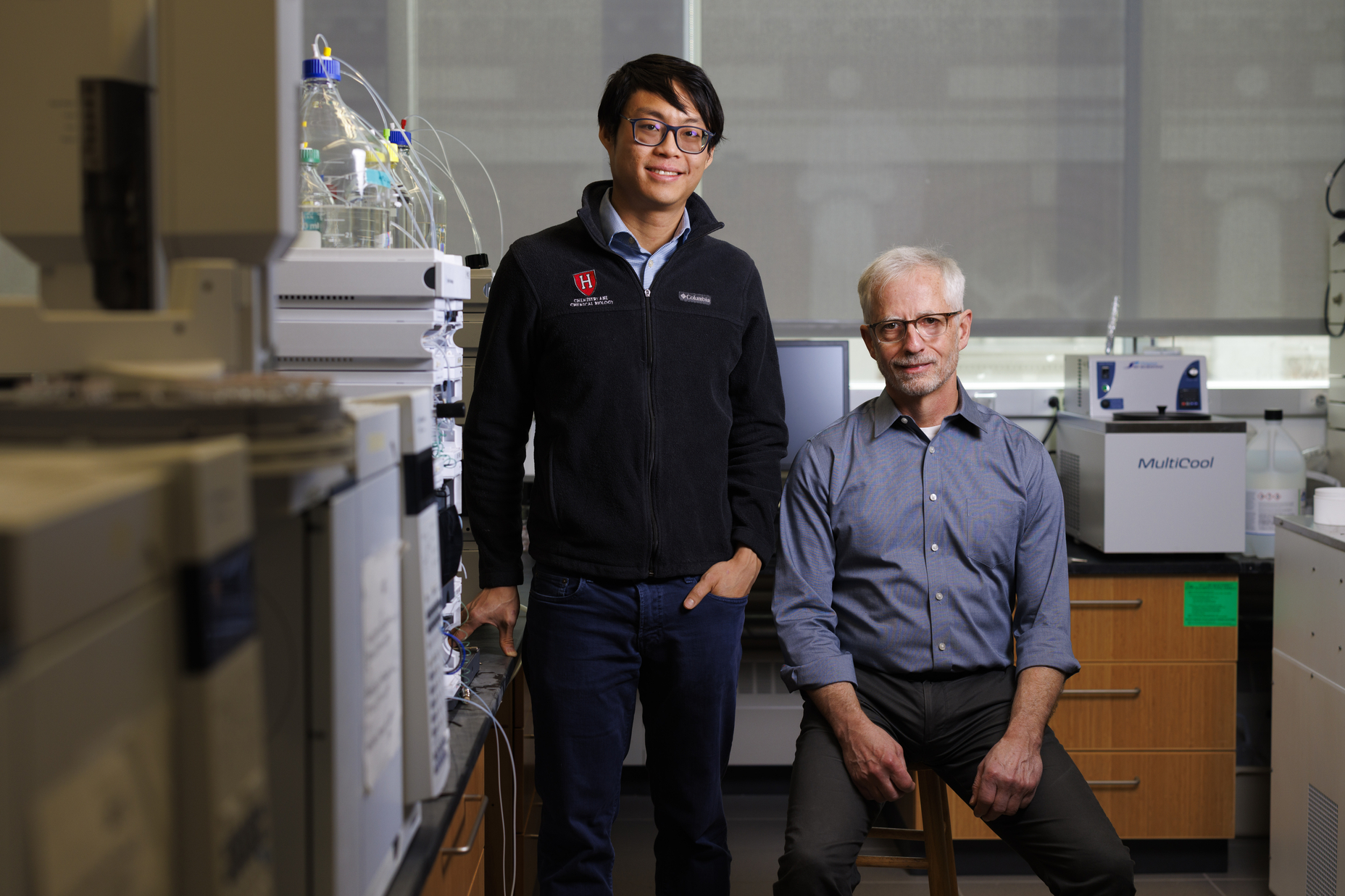

How COVID-era trick may transform drug, chemical discovery — Harvard Gazette

Laboratories turned to a smart workaround when COVID‑19 testing kits became scarce in 2020.

They mixed samples from several patients and ran a single test. If the test came back negative, everyone in it was cleared at once. If it was…

Continue Reading

-

Hubble spots three young stars going through growth spurts

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has captured a trio of young stars in the process of becoming their best selves in the constellation Scorpius. Posted to the agency’s site on January 16 as part of its Hubble Stellar Construction Zones series,…

Continue Reading

-

Drought, groundwater overuse trigger surge in sinkholes in central Türkiye-Xinhua

ISTANBUL, Jan. 16 (Xinhua) — A rapid increase in sinkholes is raising environmental and agricultural alarms in drought-stricken Konya province in central Türkiye, driven by severe groundwater depletion and climate change.

A total of 655…

Continue Reading