Whenever we need to perform a task, our cells rely on proteins to accomplish the job. Want to move? That’s a job for actin. Want to see? Rhodopsin will help you. Want to smell? That’s what olfactory receptors do. So, if proteins do…

Category: 7. Science

-

ISS astronaut medical evacuation latest news: Crew-11 astronauts prepare for SpaceX Dragon departure

Refresh

Crew-11 astronauts prepare for ISS medical evacuation

Continue Reading

-

SpaceX’s First Twilight Rideshare Carries 3D Printing Experiment Into Orbit – 3DPrint.com

- SpaceX’s First Twilight Rideshare Carries 3D Printing Experiment Into Orbit 3DPrint.com

- NASA’s Pandora Satellite, CubeSats to Explore Exoplanets, Beyond NASA Science (.gov)

- SpaceX rocket launch in California to deploy government satellite….

Continue Reading

-

NASA releases all launch dates for Artemis II. This is how soon we could be going back to the Moon

NASA’ Artemis II mission to send astronauts round the Moon and back could launch as early as 6 February 2026, the space agency has said.

Failing that, there are multiple further dates allocated for Artemis II.

The mission will see a crewed…

Continue Reading

-

ISS astronauts spy airglow and dwarf galaxy photo of the day for Jan. 13, 2026

From the ground, the night sky can feel limitless, but it’s also filtered through a blanket of air that softens and scatters starlight. From orbit, that veil drops away, as astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) saw firsthand

Continue Reading

-

Rural areas have darker skies but fewer resources for students interested in astronomy – telescopes in schools can help

The night sky has long sparked wonder and curiosity. Early civilizations studied the stars and tracked celestial events, predicted eclipses and used their observations to construct calendars, develop maps and formulate religious…

Continue Reading

-

10 asteroids named to honour ESA’s role in Planetary Defence

Space Safety 13/01/2026

38 views

2 likesIn 2025, the International Astronomical Union approved the naming of 10 asteroids after people and places associated with the European Space Agency’s…

Continue Reading

-

Strange shock wave around dead star surprises astronomers

The inset image shows dead star RXJ0528+2838 creating a shock wave as it moves through space. A strong outflow expelled from a star is usually the cause of such a shock wave. However, in the case of RXJ0528+2838, astronomers discovered that the… Continue Reading

-

Spacecraft capture the Sun building a massive superstorm

The Sun completes one full rotation about every 28 days. Because of this slow spin, observers on Earth can only see any given active region on the Sun’s surface for about two weeks. Once that region rotates away from our line of sight, it…

Continue Reading

-

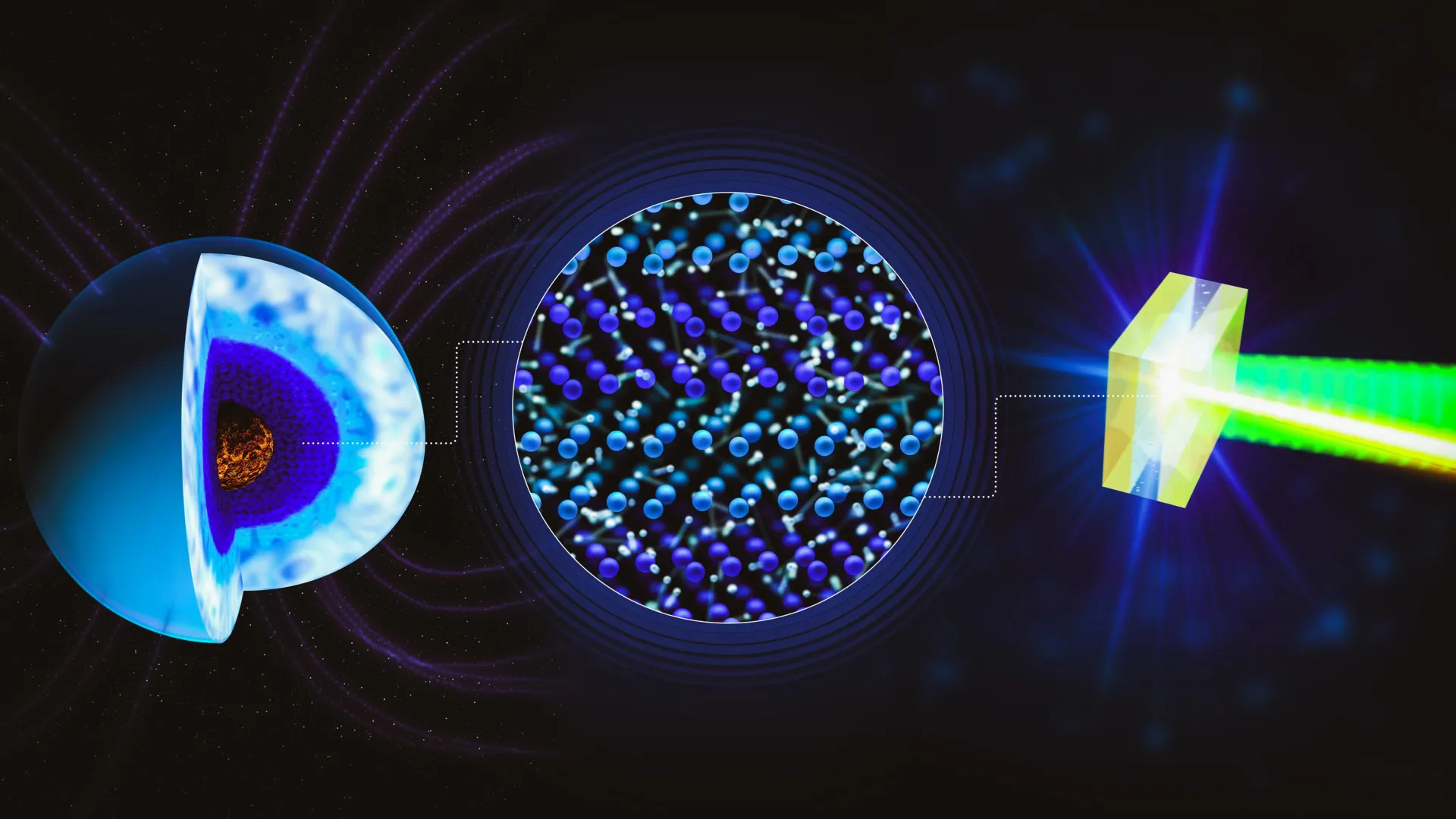

This strange form of water may power giant planets’ magnetic fields

When water is exposed to temperatures of several thousand degrees Celsius and pressures reaching millions of atmospheres, it undergoes a dramatic transformation. Under these extreme conditions, water enters a rare state known as superionic…

Continue Reading