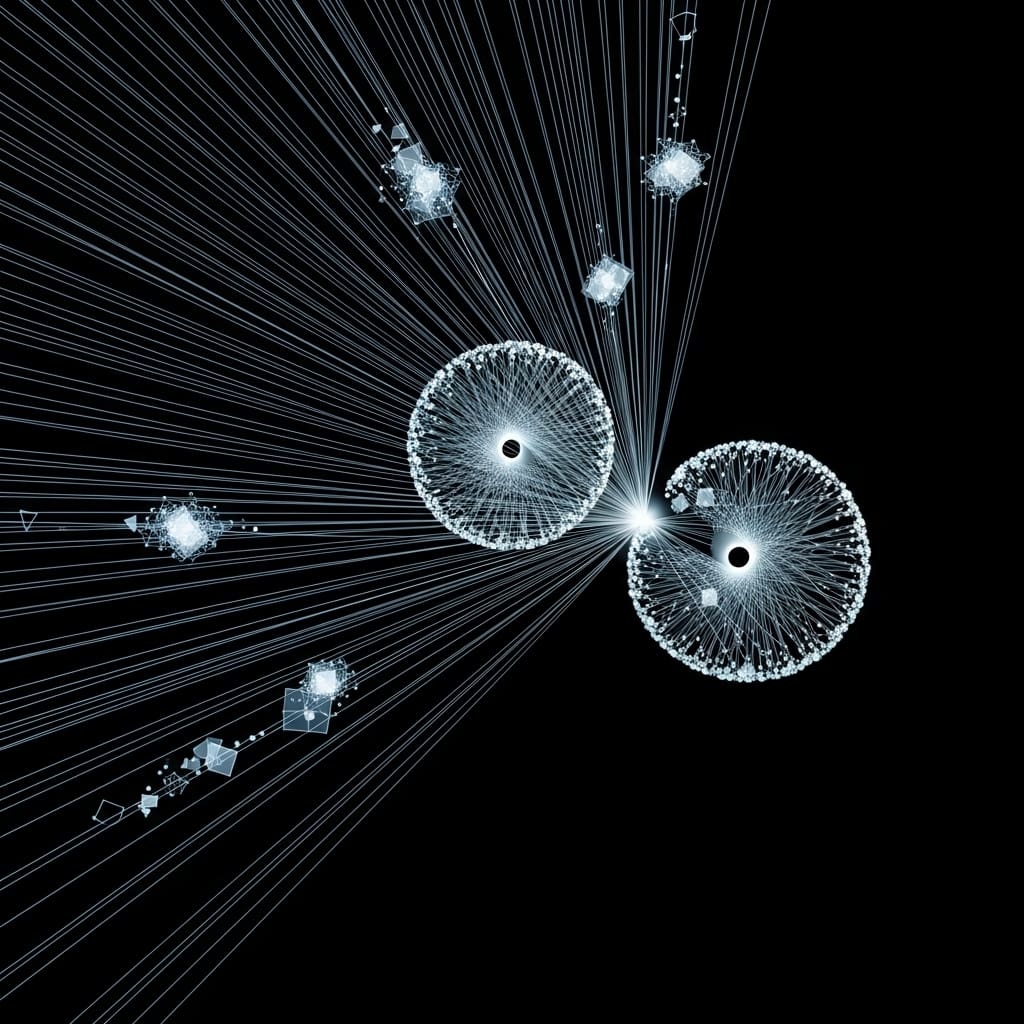

Scientists are increasingly focused on benchmarking noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices, and a new study details a method for data-driven evaluation of quantum annealing experiments. Juyoung Park, Junwoo Jung, and Jaewook Ahn, all from…

Category: 7. Science

-

Shivering Dog Locked Out Of House Sits On Her Babies To Keep Them Warm

In mid-January, temperatures in Kansas City, Kansas, dropped to 15 degrees Fahrenheit. Spending time outdoors, even in the bright sunshine, was dangerous without proper clothing.

So when a neighbor saw a pile of puppies on a front porch, huddling…

Continue Reading

-

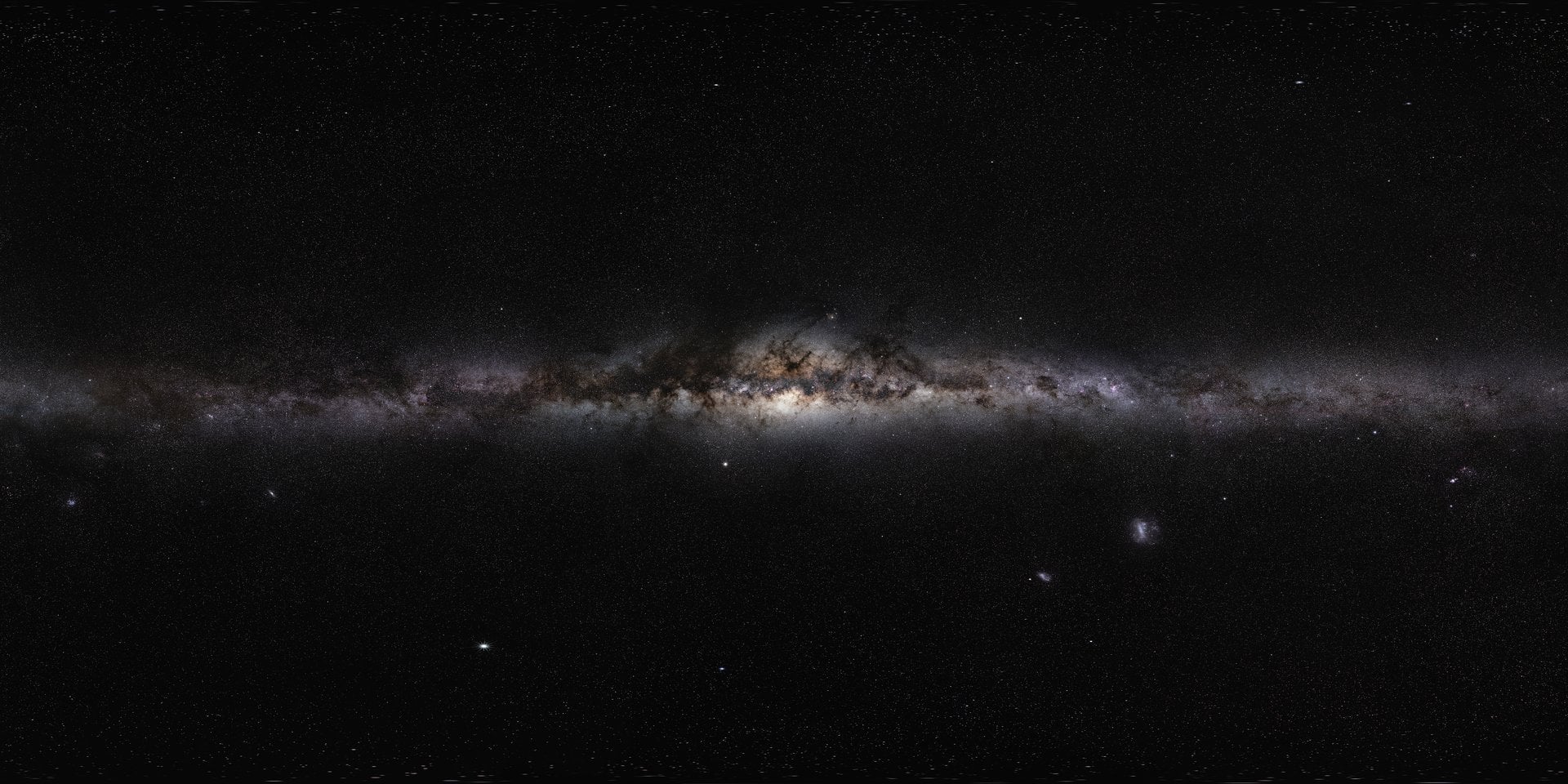

Canadian Researchers Map the Milky Way’s Magnetic Field

According to Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity and the Standard Model of Cosmology, galaxies like the Milky Way are bound together by gravity and the mysterious mass known as Dark Matter. However, magnetic fields are also vital for…

Continue Reading

-

Towards effective and ethical GenAI in chemistry education

Erümit, A. K. & Sarıalioğlu, R. Ö. Artificial intelligence in science and chemistry education: a systematic review. Discov. Educ. 4, 178 (2025).

Google Scholar

Moores, A. & Zuin Zeidler, V….

Continue Reading

-

‘Invisible scaffolding of the universe’ revealed in ambitious new James Webb telescope images

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have mapped the largest section of the universe’s dark matter yet, deepening our understanding of how this mysterious substance shapes the cosmic landscape.

Dark matter is notoriously…

Continue Reading

-

Biological Clocks Are a Mystery — This Class Tracks Them Down

We wake up in the morning and go to bed at night — most of us, at least. When we change our clocks in spring or autumn, or go on a long flight that changes our time zone, we’re left disoriented and exhausted.

Called the circadian…

Continue Reading

-

NASA Sets Coverage for Agency’s SpaceX Crew-12 Launch, Docking

NASA will stream live coverage of the upcoming prelaunch, launch, and docking activities for the agency’s SpaceX Crew-12 mission to the International Space Station.

Liftoff is targeted for no earlier than 6:01 a.m. EST on Wednesday, Feb. 11,…

Continue Reading

-

Can apes play pretend? Scientists use an imaginary tea party to find out

NEW YORK (AP) — By age 2, most kids know how to play pretend. They turn their bedrooms into faraway castles and hold make-believe tea parties.

The ability to make something out of nothing may seem uniquely human — a…

Continue Reading

-

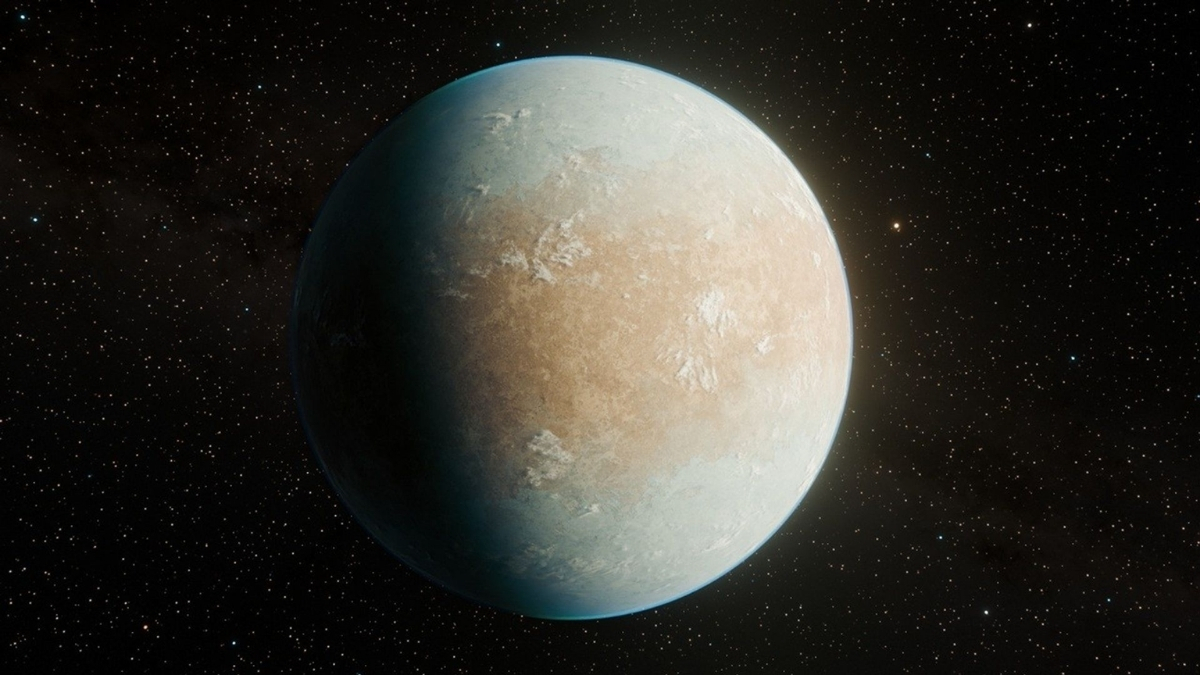

Scientists Reveal a Frozen Bizarro Earth Only 150 Light-Years Away : ScienceAlert

Astronomers have announced the discovery of what appears to be an “ice cold Earth,” a chilly but potentially habitable rocky world similar to our own located less than 150 light-years away.

As described in a recent study, this excitingly…

Continue Reading

-

Abundant Hydrocarbons In A Buried Galactic Nucleus With Signs Of Carbonaceous Grain And Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Processing – astrobiology.com

- Abundant Hydrocarbons In A Buried Galactic Nucleus With Signs Of Carbonaceous Grain And Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Processing astrobiology.com

- James Webb Space Telescope finds precursors to ‘building blocks of life’ in nearby galaxy Space

Continue Reading