An octopus’s adaptive camouflage has long inspired materials scientists looking to come up with new cloaking technologies. Now researchers have created a synthetic “skin” that independently shifts its surface patterns and colors like these…

Category: 7. Science

-

Amendment 36: New Program Element: F.19 Collaborative Opportunities for Mentorship, Partnership and Academic Success in Science

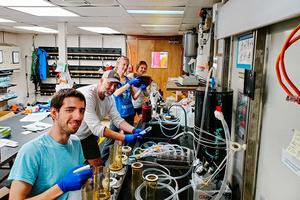

F.19 Collaborative Opportunities for Mentorship, Partnership and Academic Success in Science (COMPASS) funds collaborations between NASA Centers and academic institutions that will advance NASA’s scientific priorities and train the future…

Continue Reading

-

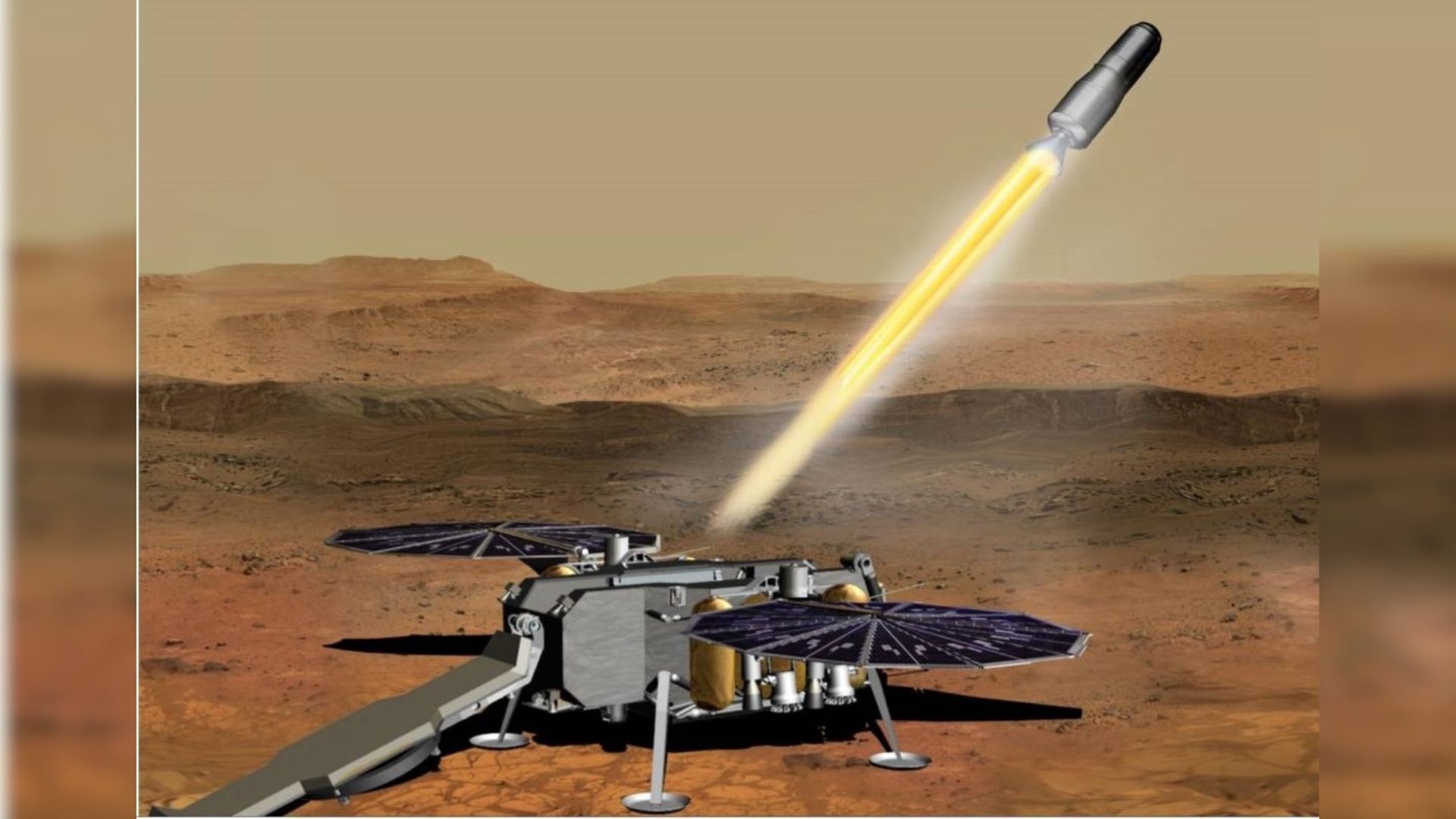

Experts push back against cancellation of NASA’s Mars sample return project

BOULDER, Colorado — The existing NASA-European Space Agency effort to establish a Mars Sample Return program is slated to be discontinued.

That’s the word according to the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, a

Continue Reading

-

Carefully-buried dog found in a 5,000-year-old Swedish bog

The Logsjömossen dog burial near Gerstaberg, Sweden, holds a 5,000-year-old dog skeleton placed beside a polished bone dagger.

Archaeologists uncovered the burial during surveys for the Ostlänken rail line, southwest of Stockholm, in December…

Continue Reading

-

'It is bittersweet': Crew-11 astronaut hands over control of ISS ahead of 1st-ever medical evacuation – Space

- ‘It is bittersweet’: Crew-11 astronaut hands over control of ISS ahead of 1st-ever medical evacuation Space

- Astronaut’s ‘serious medical condition’ forces Nasa to end space station mission early Dawn

- ISS astronaut medical evacuation latest…

Continue Reading

-

Amendment 34: A.6 Landslide Change Characterization Experiment Science Team Final Text and Due Dates

A.6 Earth Venture Suborbital-4 Landslide Change Characterization Experiment (LACCE) Science Team (ST) solicits proposals to build the full LACCE Science Team, including team members that will provide airborne and ground-based measurements,…

Continue Reading

-

NASA taps Colorado companies to lead development on telescope searching for life on other planet – Denver Gazette

- NASA taps Colorado companies to lead development on telescope searching for life on other planet Denver Gazette

- NASA seeks to accelerate development of Habitable Worlds Observatory SpaceNews

- Astroscale Unit Selected for NASA Study on Space…

Continue Reading

-

F.6 Science Activation Corrections and Other Documents posted

The Science Mission Directorate Science Activation Program encourages all people to actively participate in science through activities and resources developed by a collaborative network of project teams drawing on NASA SMD assets (science…

Continue Reading

-

SpaceX launching 29 Starlink satellites from Cape Canaveral – WESH

- SpaceX launching 29 Starlink satellites from Cape Canaveral WESH

- Launch Previews: SpaceX and ISRO to launch rideshare missions into SSO NASASpaceFlight.com –

- US SpaceX Launches 29 New Satellites into Space Qatar news agency

- Live coverage: SpaceX…

Continue Reading