Original story from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (NY, USA).

A new mass spectrometry technique sorts molecules to capture those of lower abundance.

For scientists, a molecule’s weight can help determine its makeup. For measures like…

Original story from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (NY, USA).

A new mass spectrometry technique sorts molecules to capture those of lower abundance.

For scientists, a molecule’s weight can help determine its makeup. For measures like…

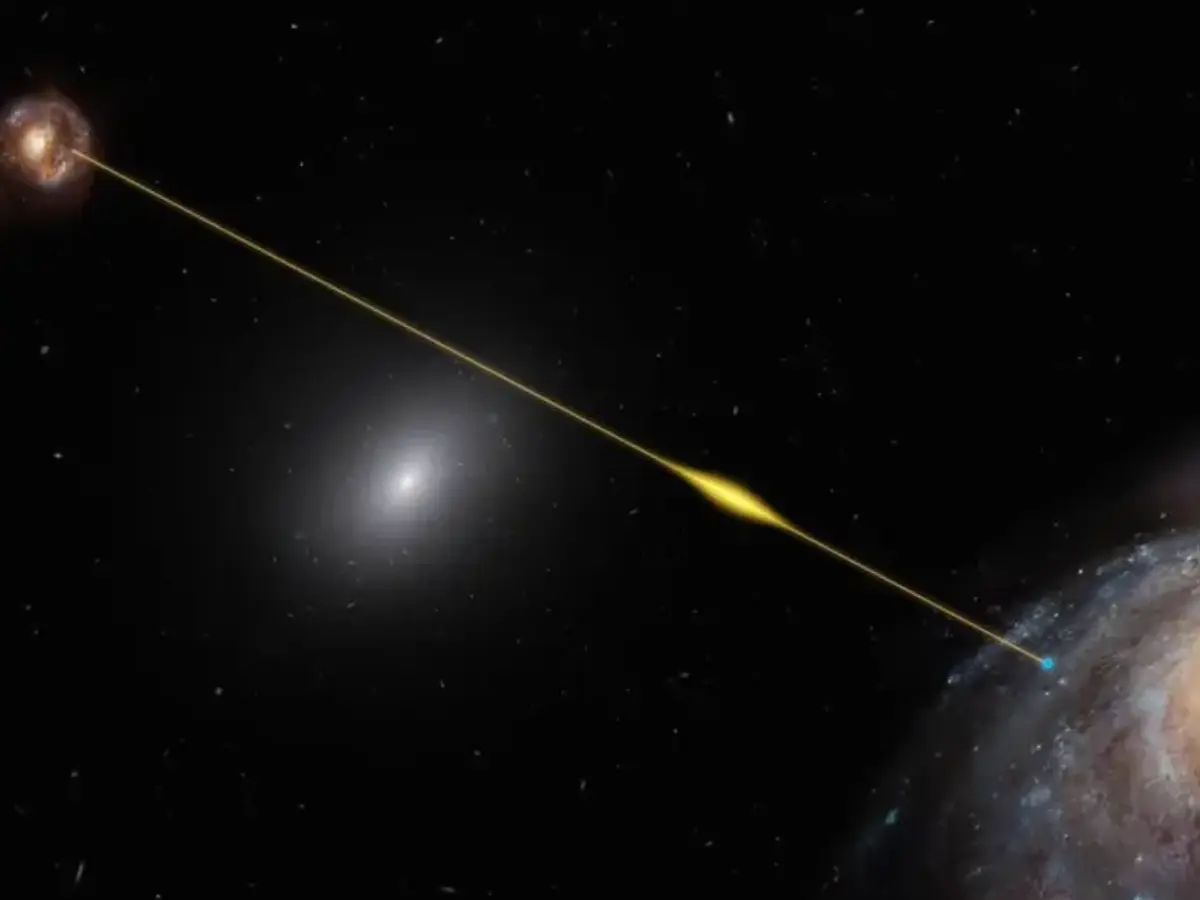

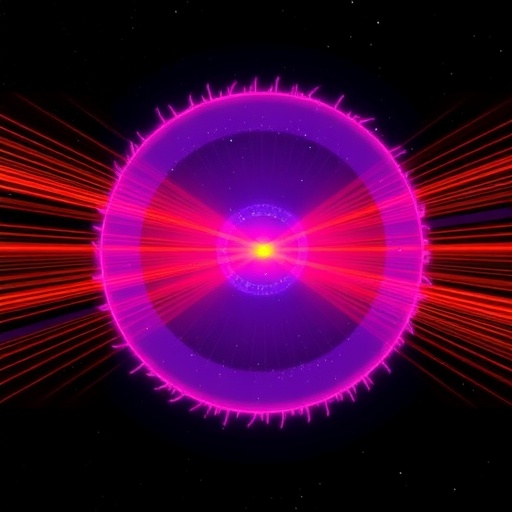

Gas and dust flowing from stars can, under the right conditions, clash with a star’s surroundings and create a shock wave. Now, astronomers using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) have imaged a…

A tiny chunk of dead star just 731 light-years away has presented astronomers with a shimmering puzzle: a powerful, glowing bow shock.

This wouldn’t be unusual under many circumstances, but in the case of the white dwarf RXJ0528+2838, there’s…

About a decade ago, scientists identified a small group of people who feel no enjoyment when listening to music, even though their hearing is normal and they experience pleasure from other activities. This phenomenon is known as “specific musical…

In a remarkable advancement likely to reshape the landscape of temperature measurement, researchers have unveiled a novel absolute thermometry method by harnessing Brillouin scattering in gases. This groundbreaking work, recently published in…

Researchers at VIB and KU Leuven have identified a molecular process that allows motor neurons to maintain protein production, a process that fails in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, reveals…

When a baby smiles at you, it’s almost impossible not to smile back. This spontaneous reaction to a facial expression is part of the back-and-forth that allows us to understand each other’s emotions and mental states.

Faces are so…