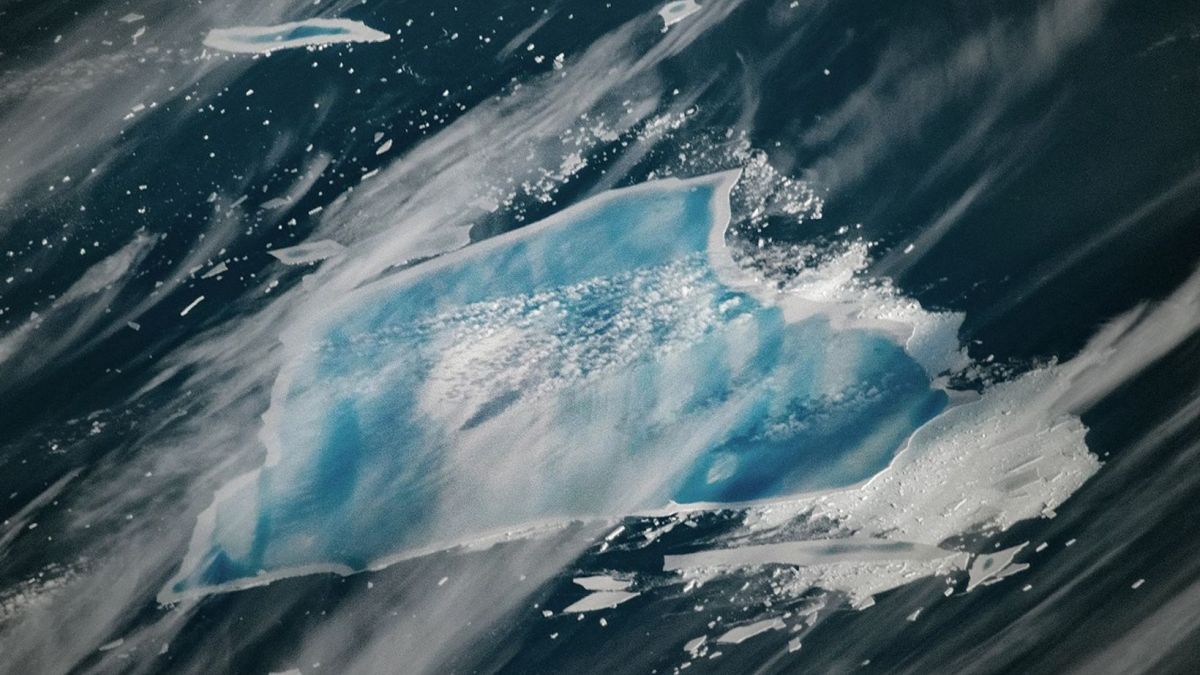

Researchers analyzing ancient seafloor sediments discovered that West Antarctica’s ice sheet has collapsed and regrown several times over millions of years — triggering earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, and tsunamis each time.

Peter Brannen started investigating the history of carbon dioxide, but ended up uncovering the story of everything.

Award-winning science journalist Peter Brannen, BC ’06, published his most recent book, The Story of CO₂ Is…