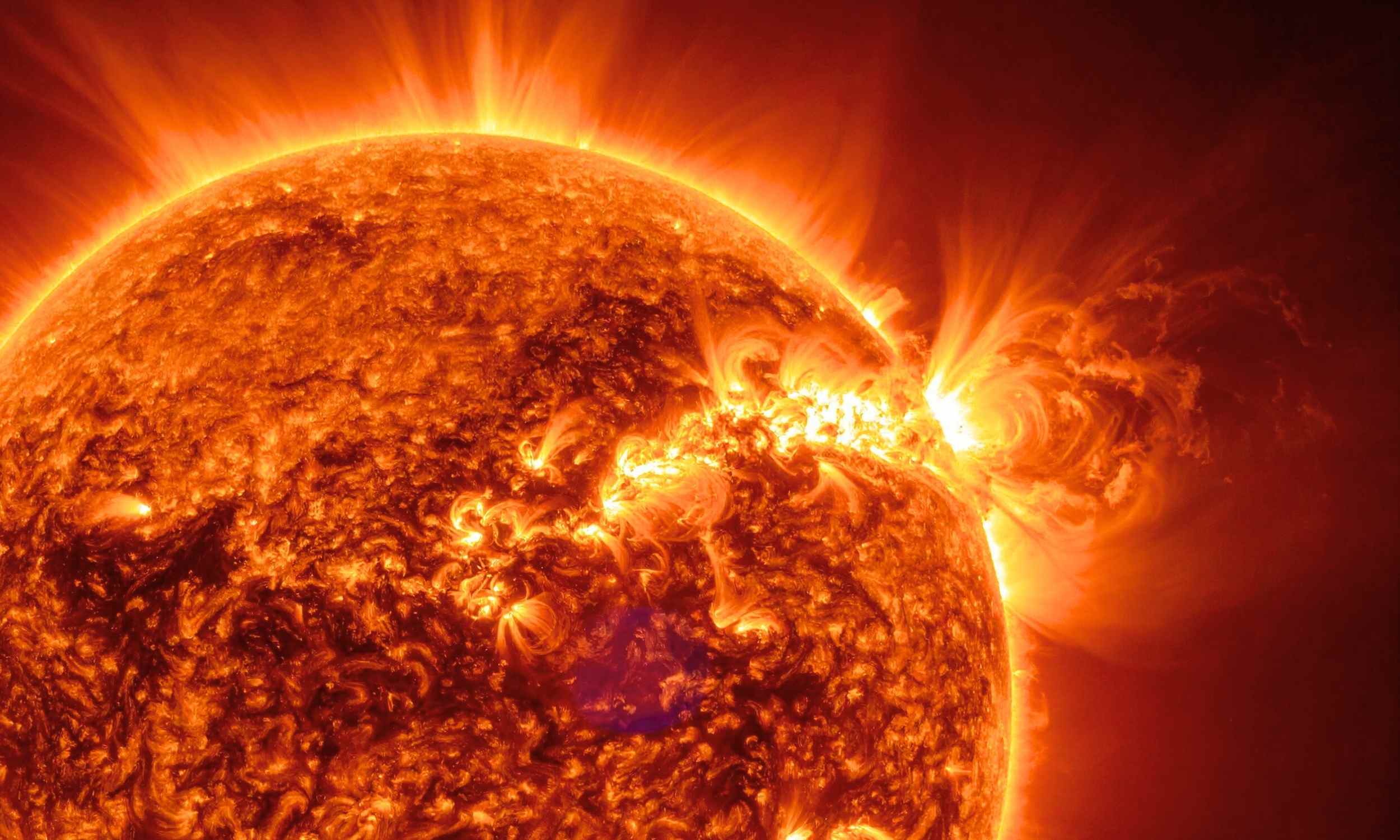

NASA has announced a new mission to study the Sun. The Chromospheric Magnetism Explorer (CMEx) was chosen over four other mission concepts that competed in earlier studies.

A team in Boulder, Colorado wants CMEx to monitor the Sun’s…

NASA has announced a new mission to study the Sun. The Chromospheric Magnetism Explorer (CMEx) was chosen over four other mission concepts that competed in earlier studies.

A team in Boulder, Colorado wants CMEx to monitor the Sun’s…

They don’t snore, and they don’t dream – but jellyfish and sea anemones were the first to present one of sleep’s core functions hundreds of millions of years ago, among the earliest creatures with nervous systems.

A groundbreaking new…

Looking into Earth’s deep past helps scientists understand what may happen as the planet warms today. One time period stands out in this search: the Paleogene Period, which began about 66 million years ago.

During this era, Earth held much more…

A pigment in red hair may have a secret superpower: It can turn a toxic threat into a splash of color.

Scientists studying the orange-to-red melanin in bird feathers have found that its production can help prevent cellular damage.

The pigment…

Qi, N. et al. Temporal and Spatial distribution analysis of atmospheric pollutants in Chengdu–Chongqing twin-city economic circle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 4333 (2022).

The next time you reach for a memory or make a quick choice, a storm of tiny signals races through your brain. Scientists can usually see only half of that storm. Now, a new engineered protein finally lets them watch the quiet half too, the…

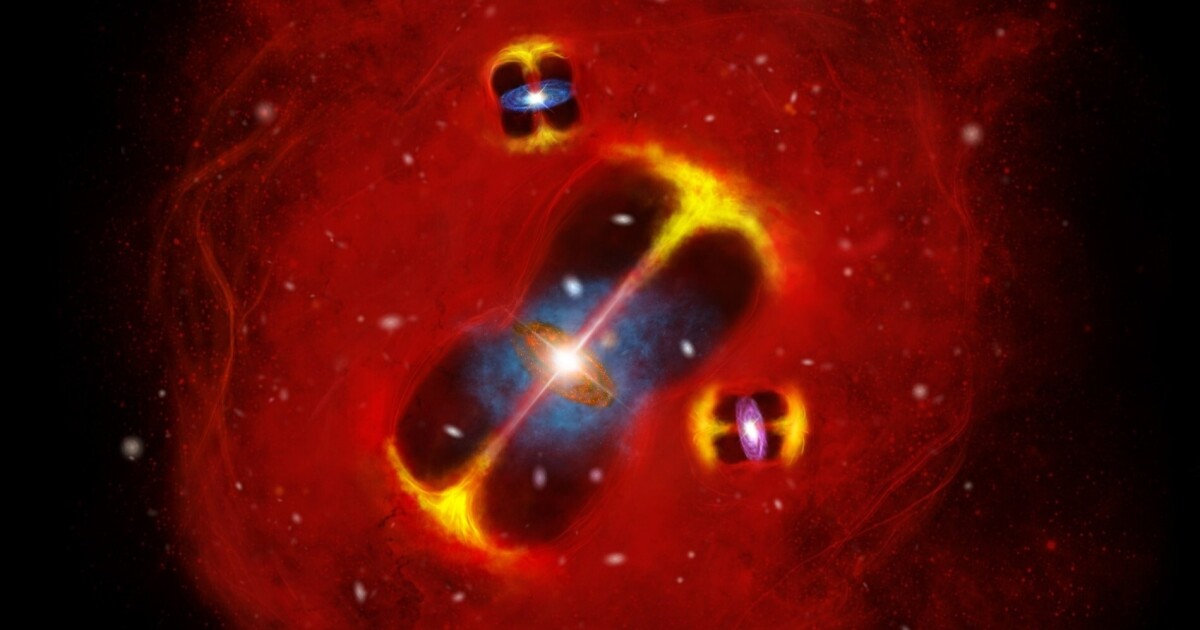

Current theories say young galaxy clusters should be relatively cool compared to older ones. But researchers recently found a very young cluster that was shockingly hot.

Study author Dazhi Zhou says it’s…