Around lunchtime on March 1st, 2024, Patrick Roycroft, geology curator at the National Museum of Ireland, was given a piece of mineral, about the size of a Creme Egg, by a seven-year-old boy called Ben O’Driscoll. Just a few weeks earlier, in…

Category: 7. Science

-

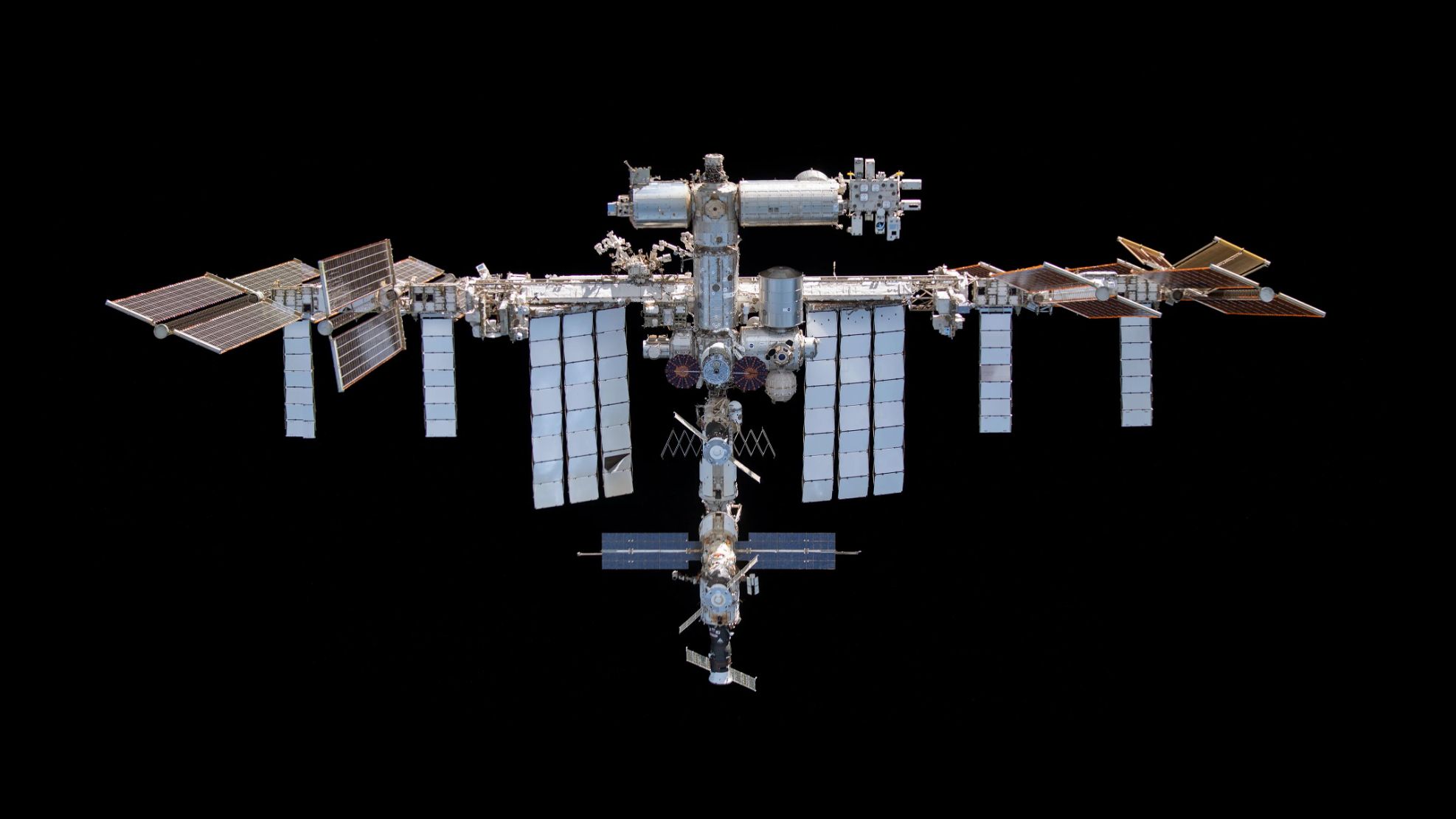

NASA will evacuate SpaceX Crew-11 astronauts from International Space Station on Jan. 14

We now know when the first medical evacuation in the history of the International Space Station will take place.

On Friday night (Jan. 9), NASA announced that it’s targeting Wednesday (Jan. 14) for the earlier-than-expected departure of SpaceX’s…

Continue Reading

-

Country diary: Look up! Tonight’s the night to see Jupiter at its brightest | Jupiter

As unmissable as new year’s fireworks, the wolf moon held the heavens for the first few nights of January, casting an unearthly radiance over everything, night almost as bright as day. Now, as that moon wanes, prepare to be wowed by a true…

Continue Reading

-

We may be able to turn Mars green. Here’s how science says we’ll make the Red Planet habitable

Is it possible to terraform the planet Mars, turning it from a barren, hostile wasteland into a world fit for human habitation?

As NASA’s Artemis missions – seen as a stepping stone to eventually landing human feet on Mars – are ramping up,…

Continue Reading

-

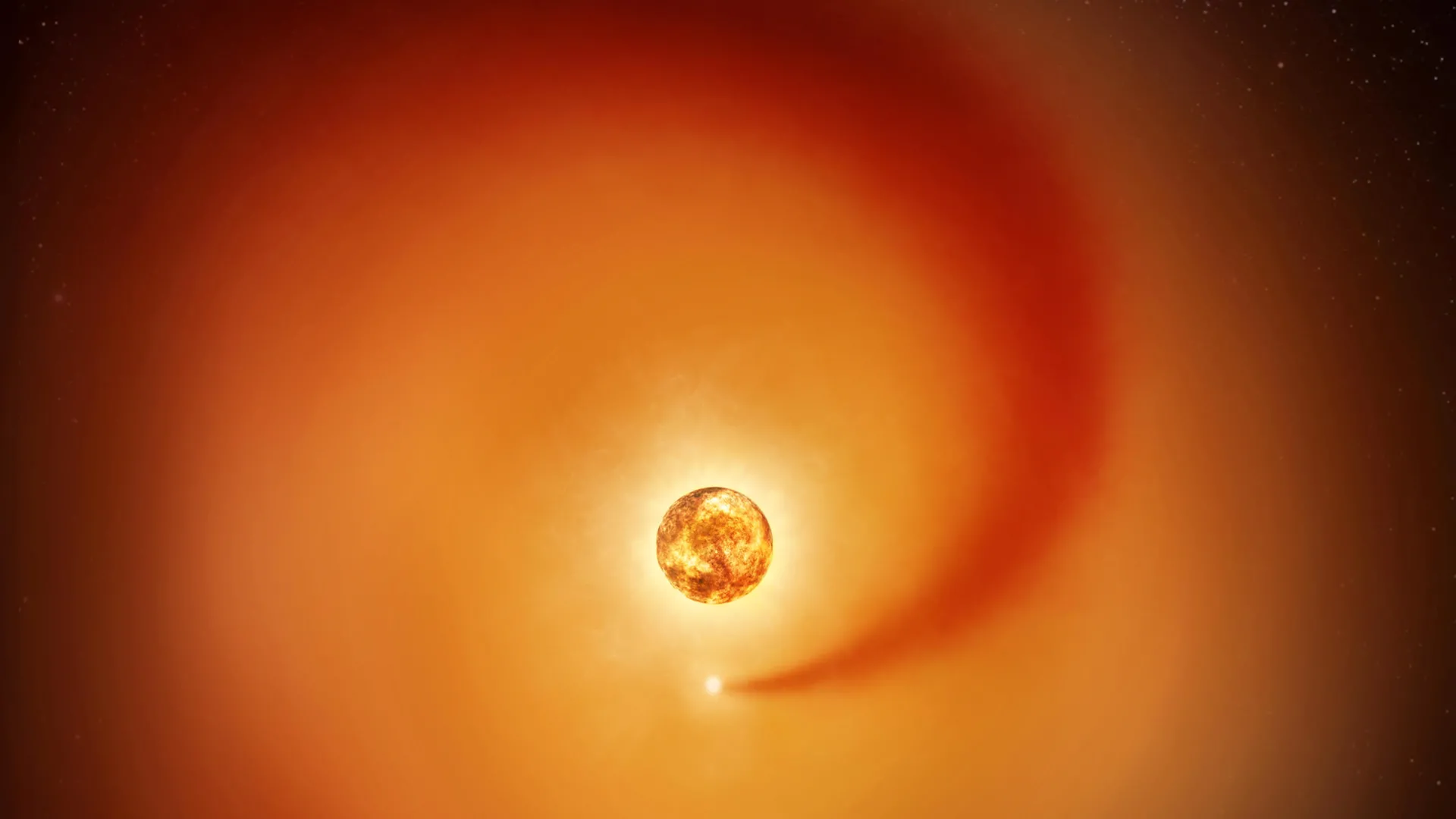

Betelgeuse has a hidden companion and Hubble just caught its wake

Astronomers analyzing fresh observations from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and several ground-based observatories have uncovered clear signs that a recently identified companion star is shaping the environment around Betelgeuse. The study, led…

Continue Reading

-

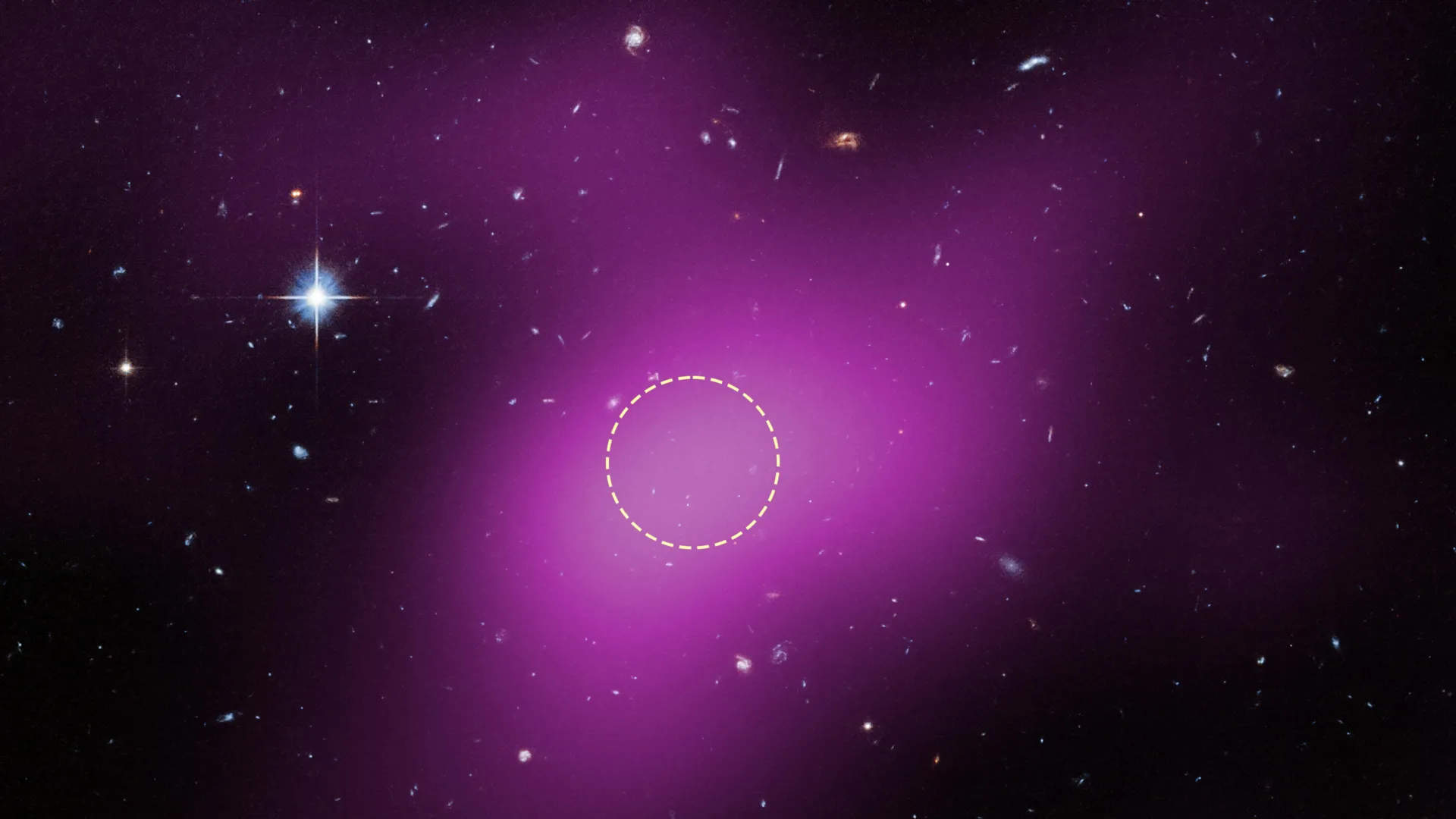

Astronomers find a ghost galaxy made of dark matter

Astronomers working with the Hubble Space Telescope have identified an entirely new type of cosmic object. It is a cloud rich in gas and dominated by dark matter, yet it contains no stars. Scientists consider it a relic left behind from the…

Continue Reading

-

Study uncovers a neural brake that limits motivation during unpleasant situations

Background

Most of us know the feeling: maybe it is making a difficult phone call, starting a report you fear will be criticized, or preparing a presentation that’s stressful just to think about. You understand what needs to be…

Continue Reading

-

NASA, SpaceX set target date for Crew-11’s return to earth – Reuters

- NASA, SpaceX set target date for Crew-11’s return to earth Reuters

- Astronaut’s ‘serious medical condition’ forces Nasa to end space station mission early Dawn

- NASA Postpones Jan. 8 Spacewalk NASA (.gov)

- NASA considering bringing…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists identify a molecular switch that controls water flow in the gut

Although constipation and diarrhea may seem like opposite problems, they both hinge on the same underlying issue: how much fluid moves into the gut. These common issues affect millions of people in the U.S. each year, yet scientists…

Continue Reading

-

Active mechanical forces drive how bacteria switch swimming direction

Scientists have uncovered a new explanation for how swimming bacteria change direction, providing fresh insight into one of biology’s most intensively studied molecular machines.

Bacteria move through liquids using propellerlike…

Continue Reading