BREVARD, N.C. (WLOS) — A man was injured after he was struck by a truck while crossing North Broad Street in Brevard on Friday morning.

According to Brevard police, a vehicle had slowed to allow the man to cross when a Toyota Tacoma bypassed it,…

BREVARD, N.C. (WLOS) — A man was injured after he was struck by a truck while crossing North Broad Street in Brevard on Friday morning.

According to Brevard police, a vehicle had slowed to allow the man to cross when a Toyota Tacoma bypassed it,…

(WLOS) — This weekend, Jupiter becomes its biggest, brightest, and closest of the year, outshining every star in the sky.

Jupiter will be at opposition. Earth will be directly between the giant planet and the Sun.

In opposition, Jupiter rises at…

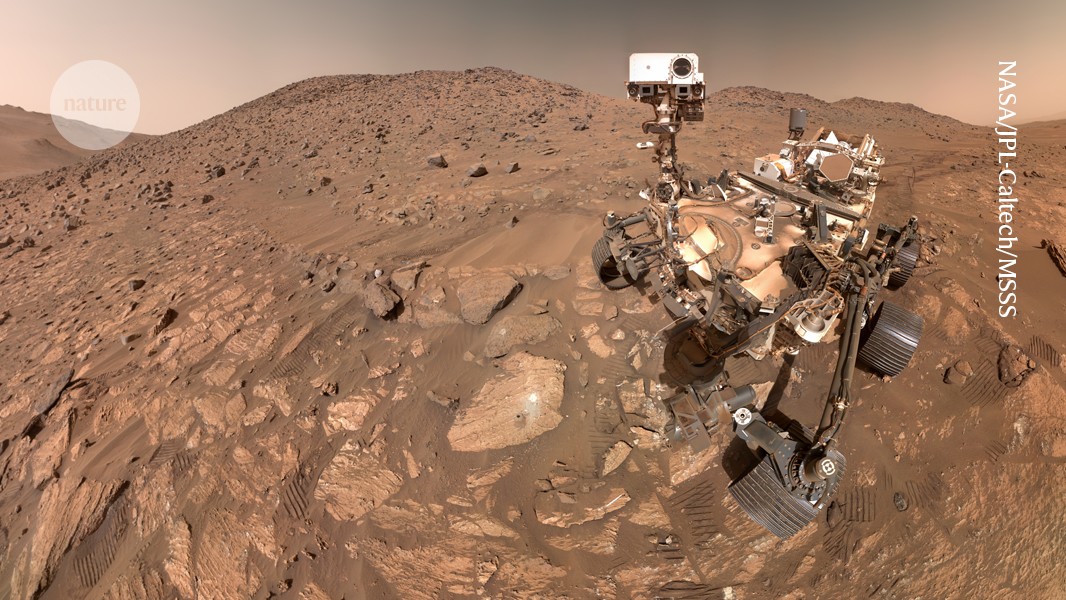

NASA’s Mars Perseverance rover poses for a selfie after drilling a sample from Cheyava Falls, the arrowhead-shaped rock in the centre of this picture. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Far away on desolate Mars, a set of dust and rock samples…

With data collected months before its main survey is due to begin, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is already upending what we thought we knew about asteroids.

In the Main Belt of asteroids between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, the telescope…

ALTOONA, Pa. — Brian Onishi, associate professor of philosophy at Penn State Altoona, was an invited speaker for a session at the annual meeting of the Eastern American Philosophical Association held this week in Baltimore.

The session was…

Swimming at a crawl with cloudy eyes and mottled skin, the Greenland shark looks like it’s seen better days.

The shark’s eyes were thought to be barely functional, as it spends most of its time in pitch black waters up to 3,000 metres deep.

And…

Pallab Ghosh,Science Correspondentand

Alison Francis

NASA

NASAThe first crewed Moon mission in more than 50 years could be launched by…