Now more than 53 years since humans last went to the moon, NASA will be going back with the Artemis missions.

Spending more than nine years in development and facing countless setbacks, the crew of Artemis II could return to the moon…

Now more than 53 years since humans last went to the moon, NASA will be going back with the Artemis missions.

Spending more than nine years in development and facing countless setbacks, the crew of Artemis II could return to the moon…

A common belief holds that…

We start this week with a bit of a good news/bad news situation. On February 6th, the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) was shut down after 25 years of operation. Located at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York, the…

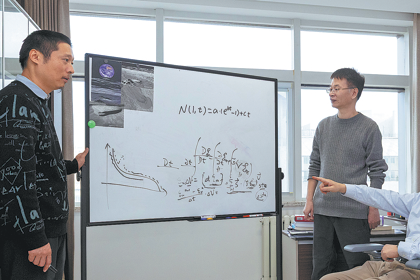

In order to better study Earth’s radiation patterns, some scientists are now suggesting a turn to lunar observations. Scientists from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) in the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently conducted a study…

Thomas, C. D. et al. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427, 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02121 (2004).

Tam et al. Research on climate change in social psychology…

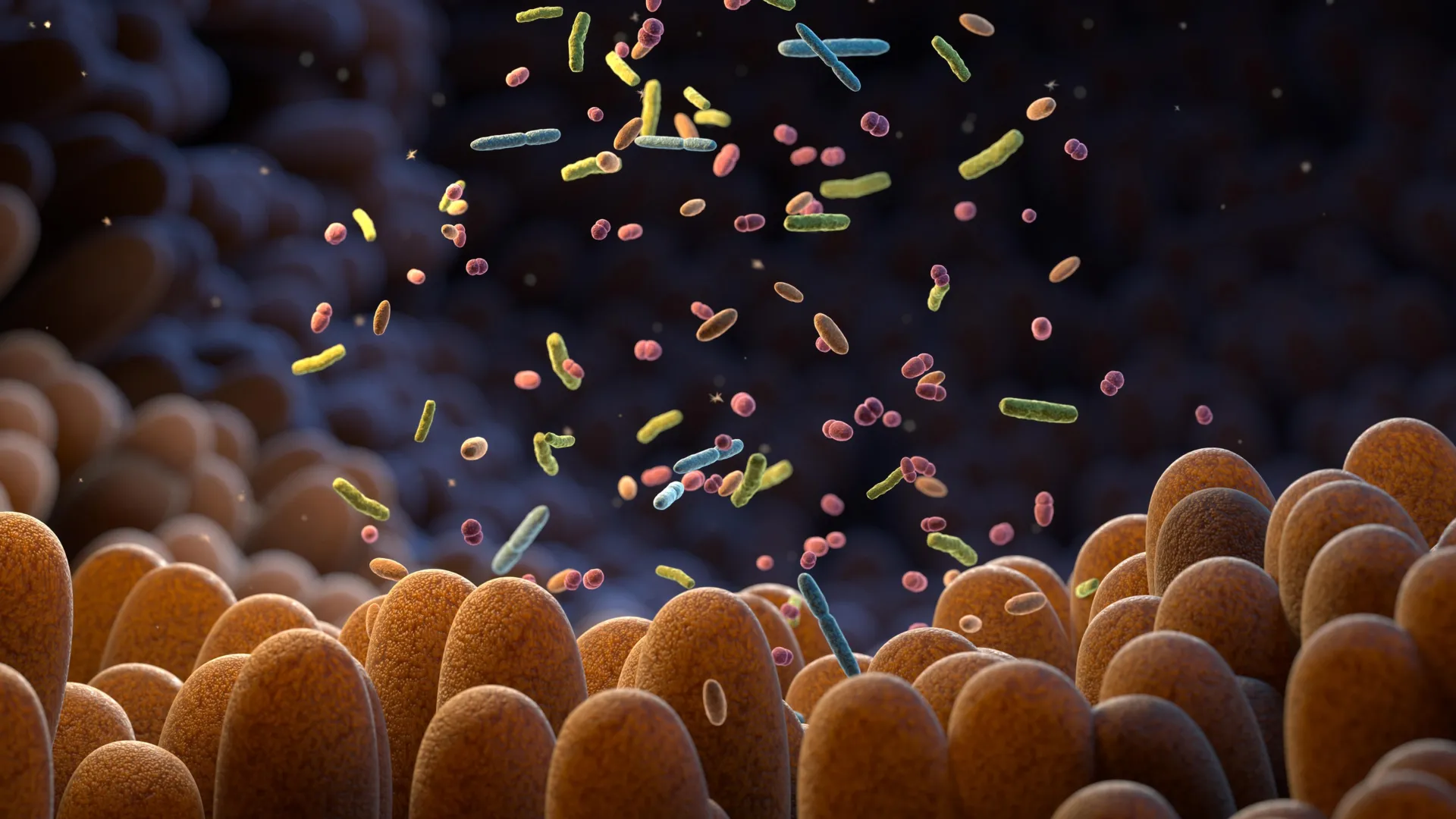

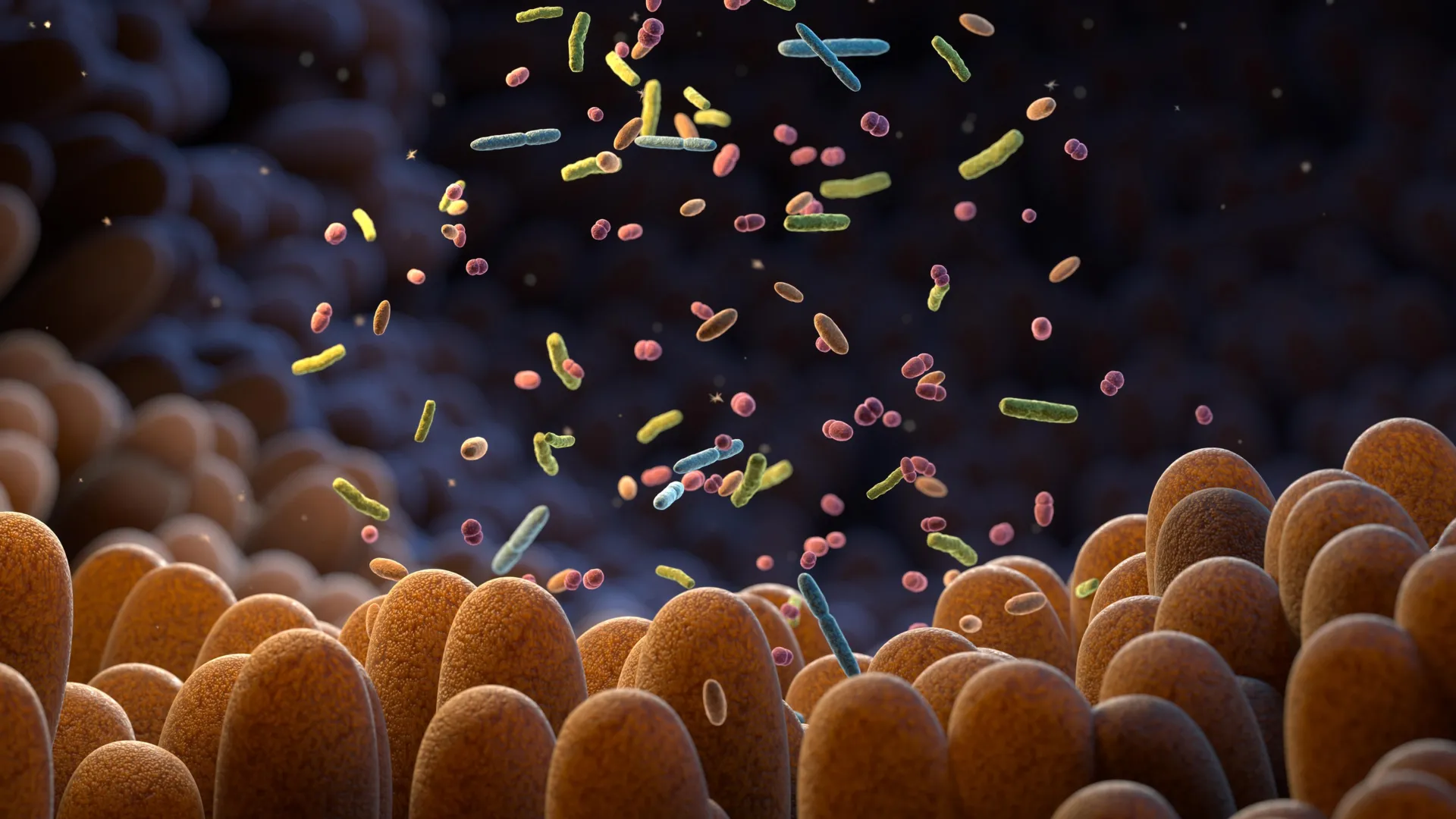

The gut microbiome, also called the gut flora, plays a vital role in human health. This enormous and constantly changing community of microorganisms is shaped by countless chemical exchanges, both among the microbes themselves and between…

The gut microbiome, also called the gut flora, plays a vital role in human health. This enormous and constantly changing community of microorganisms is shaped by countless chemical exchanges, both among the microbes themselves and between…

The Aurora Borealis and Australis have dazzled and inspired all those who have beheld them since time immemorial. Much like the Moon, stars, constellations, and planets, they are considered a permanent part of our shared cultural…

Two Americans, a French astronaut and a Russian cosmonaut said Sunday they are eager to blast off Wednesday on a flight to the International Space Station, replacing four crew members who cut their mission short and returned to Earth last month…