- TRPM5 protein helps the body sense taste, control blood sugar and defend the gut

- Scientists found hidden control site in TRPM5 that can activate and inhibit its function

- …

Category: 7. Science

-

Hidden molecular switch controls taste, metabolism and gut function: For Journalists

-

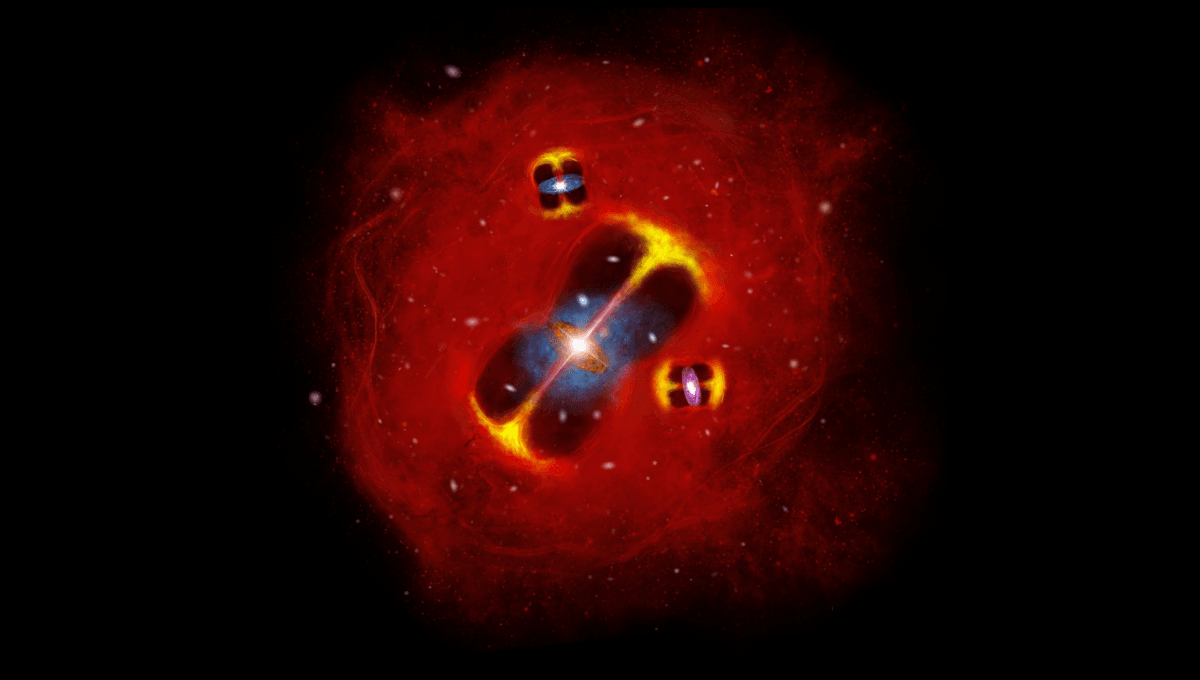

Hottest And Earliest Galaxy Cluster Gas Ever Found Could Challenge Current Cosmological Models

It seems that in the last few years, we have been collecting a lot of objects, phenomena, and events that challenge our best understanding of how the universe and galaxies in it have evolved. Thanks to new telescopes coming online, we are seeing…

Continue Reading

-

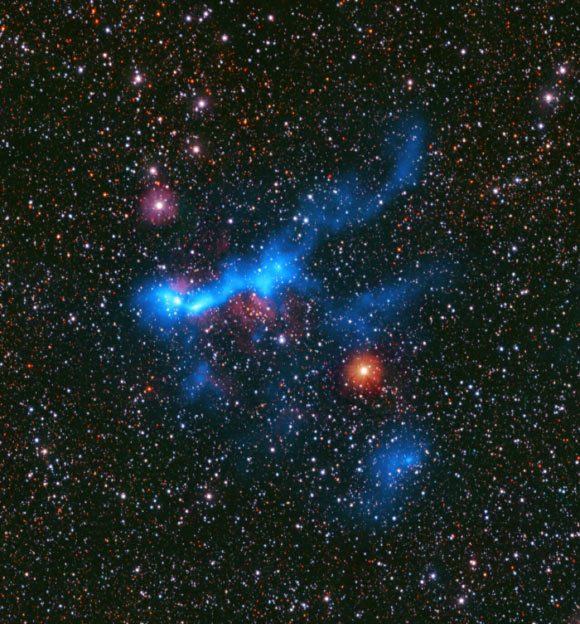

CAFFEINE Provides New Insights into How Stars Form in Dense Gas

Astronomers have released the new results from the CAFFEINE survey, shedding new light on a long-standing mystery: what controls the efficiency of star formation in the densest parts of galaxies?

This image shows the massive star-forming…

Continue Reading

-

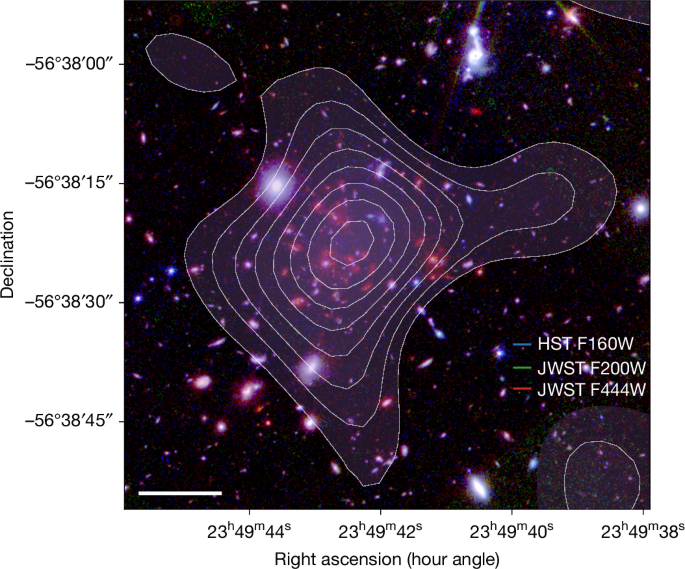

Sunyaev–Zeldovich detection of hot intracluster gas at redshift 4.3

Bryan, G. L. & Norman, M. L. Statistical properties of X-ray clusters: analytic and numerical comparisons. Astrophys. J. 495, 80–99 (1998).

Google Scholar

Chiang, Y.-K., Makiya, R.,…

Continue Reading

-

Greenland’s Prudhoe Dome ice cap was completely gone only 7,000 years ago, first GreenDrill study finds – University at Buffalo

- Greenland’s Prudhoe Dome ice cap was completely gone only 7,000 years ago, first GreenDrill study finds University at Buffalo

- Northern Greenland ice dome melted before and could melt again New Scientist

- What these ancient clues tell us about…

Continue Reading

-

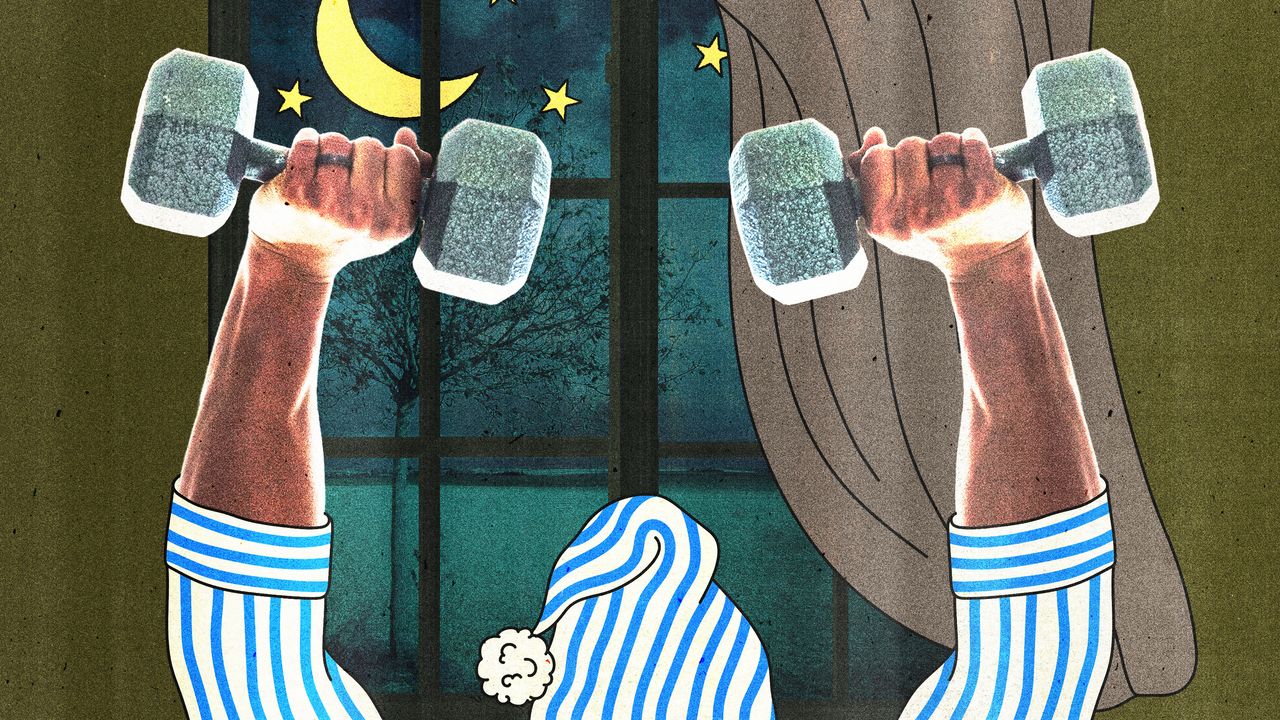

The Best Time to Exercise Before Bed

There are some logical things we know to be true: working out is tiring. And being tired helps you fall asleep. But exercise before bed can sometimes have the opposite effect. I have personal experience with this: At one point I was attending a

Continue Reading

-

Mars Curiosity Rover Observes Sulfur Crystals – astrobiology.com

- Mars Curiosity Rover Observes Sulfur Crystals astrobiology.com

- Mars Curiosity rover cracked open a rock and finds an element that should not be there Earth.com

- Curiosity drove over a rock on Mars, accidentally breaking it, and what appeared…

Continue Reading

-

Impossibly Hot Object Discovered 1.4 Billion Years After The Big Bang

A ‘shadow’ cast on the faint, leftover glow of the Big Bang has revealed a giant object in the early Universe that defies our predictions of how the Universe should evolve.

It’s a galaxy cluster named SPT2349-56. Spotted a mere 1.4 billion years…

Continue Reading

-

Earliest, hottest galaxy cluster gas on record challenges cosmological models – Phys.org

- Earliest, hottest galaxy cluster gas on record challenges cosmological models Phys.org

- Earliest, hottest galaxy cluster gas on record could change cosmological models UBC Science

- Impossibly Hot Object Discovered 1.4 Billion Years After The Big…

Continue Reading

-

"Too Strong to Be Real": Astronomers Stunned by Boiling Gas in the Early Universe – SciTechDaily

- “Too Strong to Be Real”: Astronomers Stunned by Boiling Gas in the Early Universe SciTechDaily

- Earliest, hottest galaxy cluster gas on record could change cosmological models UBC Science

- Impossibly Hot Object Discovered 1.4 Billion Years After…

Continue Reading