For more than 50 years, scientists have searched for alternatives to silicon as the foundation of electronic devices built from molecules. While the concept was appealing, practical progress proved far more difficult. Inside real devices,…

Category: 7. Science

-

A Hidden Source of Power May Have Been Discovered Surrounding Our Cells : ScienceAlert

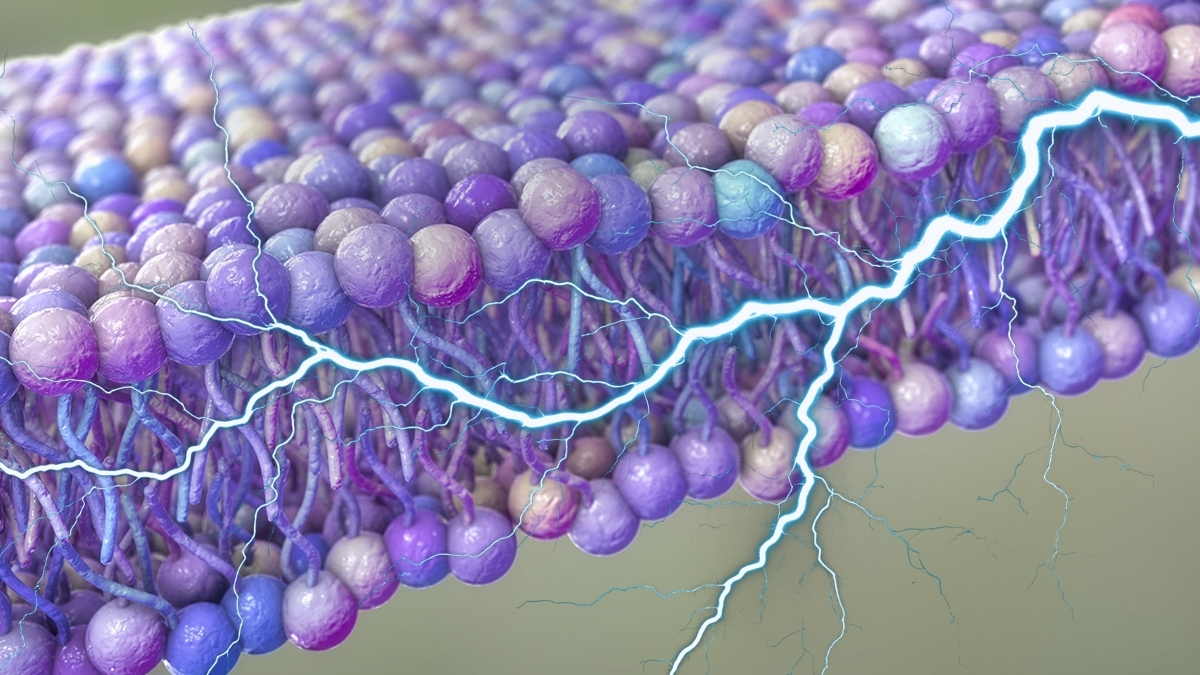

Our cells may literally ripple with electricity, acting as a hidden power supply that could help transport materials or even play a role in our body’s communication.

Researchers from the University of Houston and Rutgers University in the US…

Continue Reading

-

A Hidden Source of Power May Have Been Discovered Surrounding Our Cells

Our cells may literally ripple with electricity, acting as a hidden power supply that could help transport materials or even play a role in our body’s communication.

Researchers from the University of Houston and Rutgers University in the US…

Continue Reading

-

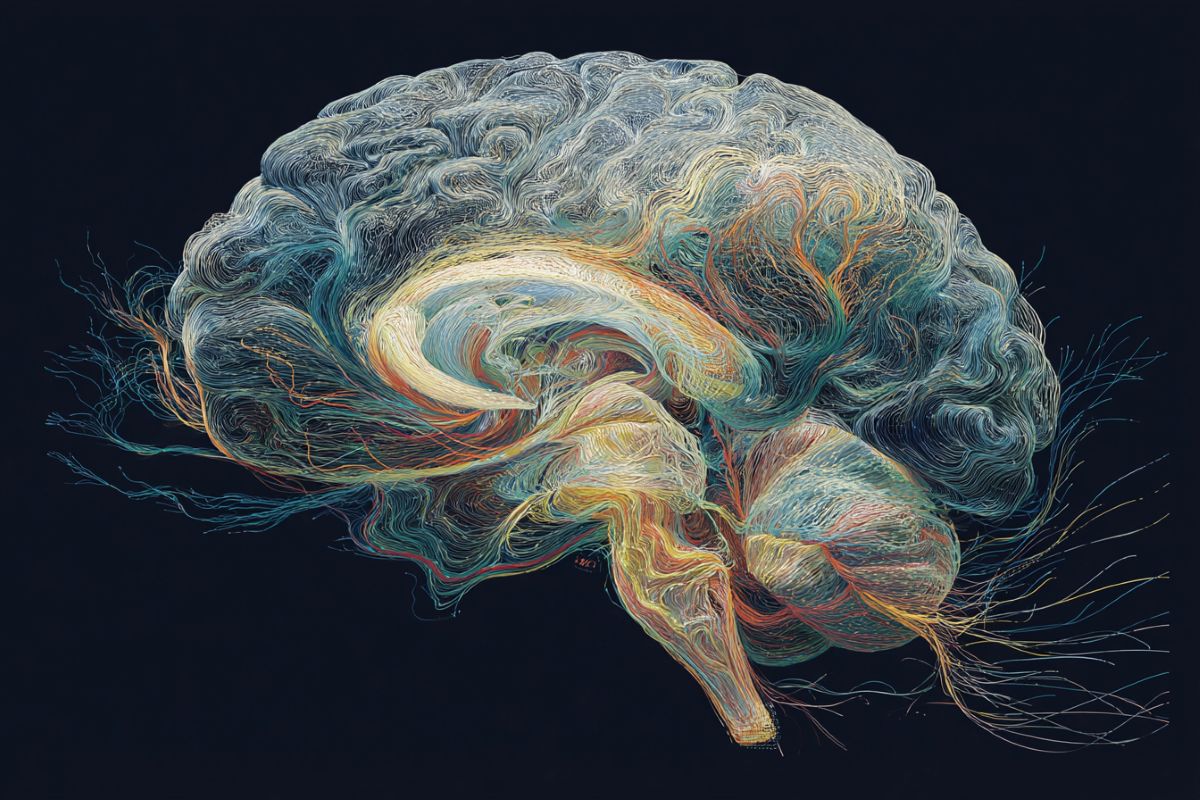

Brain Blends Fast and Slow Signals to Shape Human Thought

Summary: Researchers mapped the brain connectivity of 960 individuals to uncover how fast and slow neural processes unite to support complex behavior. They found that intrinsic neural timescales—each region’s characteristic window for…

Continue Reading

-

Kona coast on Big Island becoming central spot for innovative coral reef restoration : Maui Now

The Nature Conservancy’s Julia Rose prepares to reattach coral to the reef in Kahuwai Bay. (Photo Credit: Kaikea Nakachi/Hui Kahuwai) copy Earlier this month, a team of scientific divers, snorkelers and boat crews carefully recovered and…

Continue Reading

-

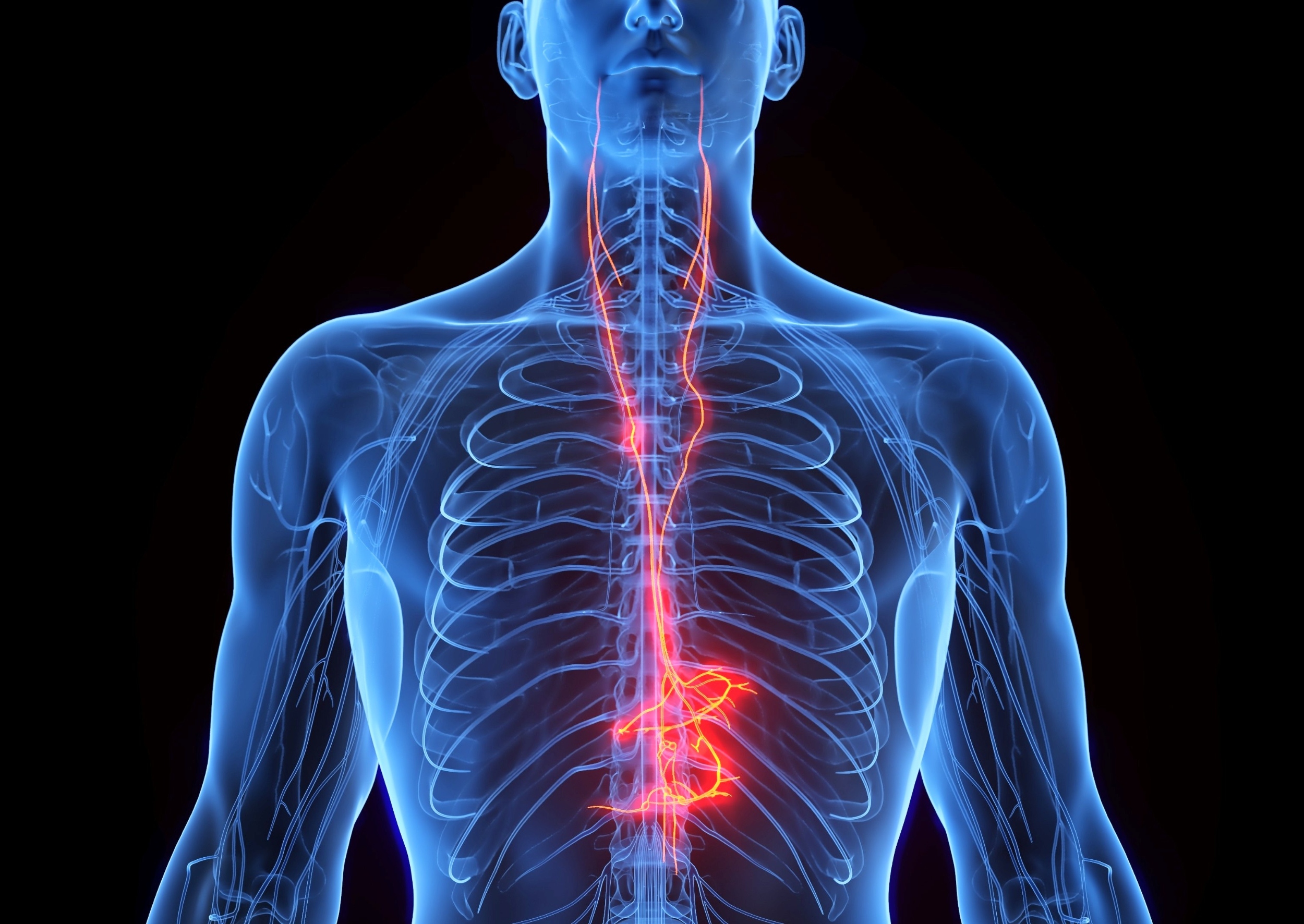

Tiny nerve plays a big role in keeping the heart young

Aging doesn’t just show on your face – it shows up in your heart too. As the years pass, heart muscle stiffens, cells don’t work as well as they once did, and the risk of heart failure slowly rises.

For a long time, doctors have focused on…

Continue Reading

-

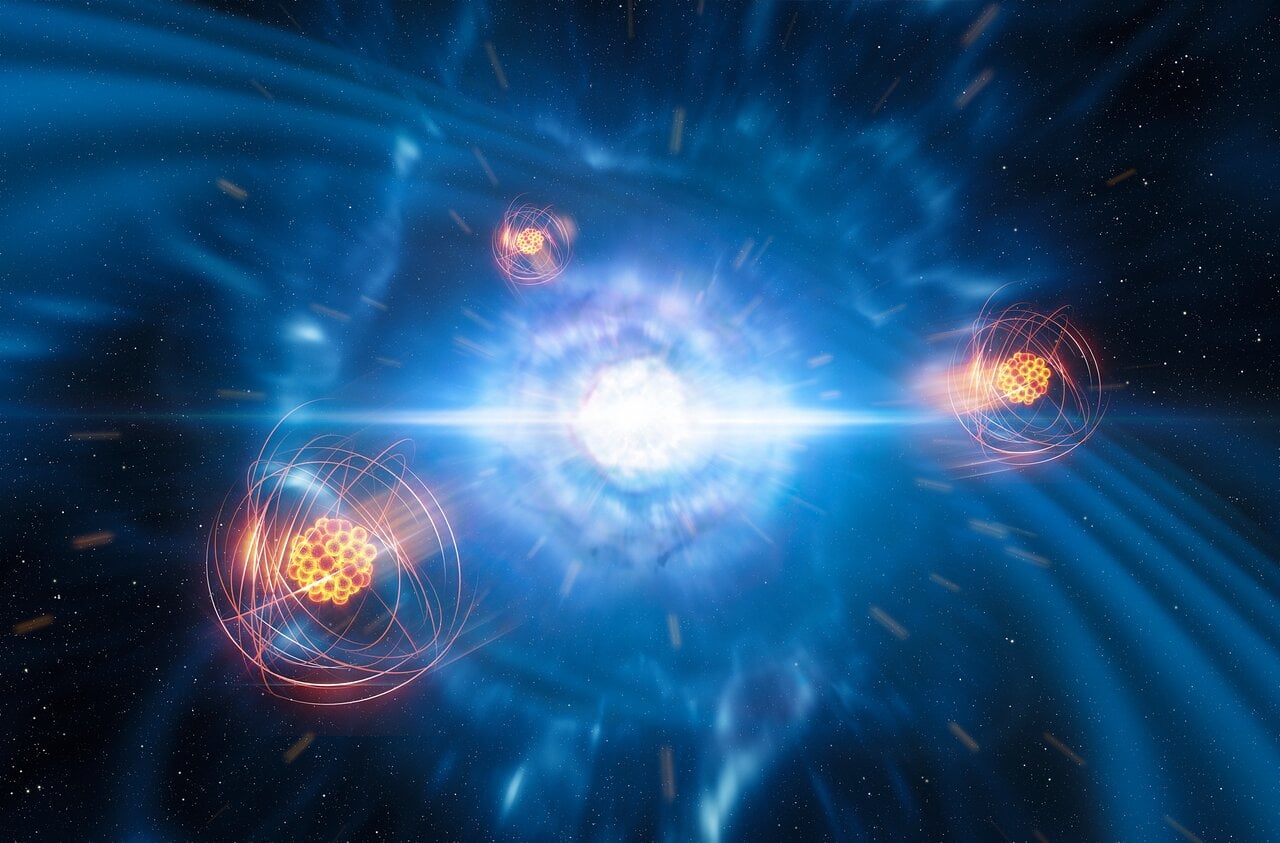

Earth-like Planets Need a Cosmic-Ray Bath

It’s quite a challenge to make an Earth-like world. You need enough mass to hold an atmosphere and generate a good magnetic field, but not so much mass that you hang on to light elements such as hydrogen and helium. You also need to be…

Continue Reading

-

Were black holes born before stars? JWST finds a troubling case

When astronomers look deep into the early universe, they don’t expect to see fully developed cosmic objects but small galaxies, young stars, and black holes still struggling to grow.

However, recent observations with the James Webb Space…

Continue Reading

-

Quadrantids meteor shower to peak: When and how to watch it in India – MSN

- Quadrantids meteor shower to peak: When and how to watch it in India MSN

- This Week’s Sky at a Glance, January 2 – 11 Sky & Telescope

- Meteor Activity Outlook for January 3-9, 2026 American Meteor Society

- The Quadrantid meteor shower peaks…

Continue Reading