A small section of the International Space Station that has experienced persistent leaks for years appears to have stopped venting atmosphere into space.

The leaks were caused by…

A small section of the International Space Station that has experienced persistent leaks for years appears to have stopped venting atmosphere into space.

The leaks were caused by…

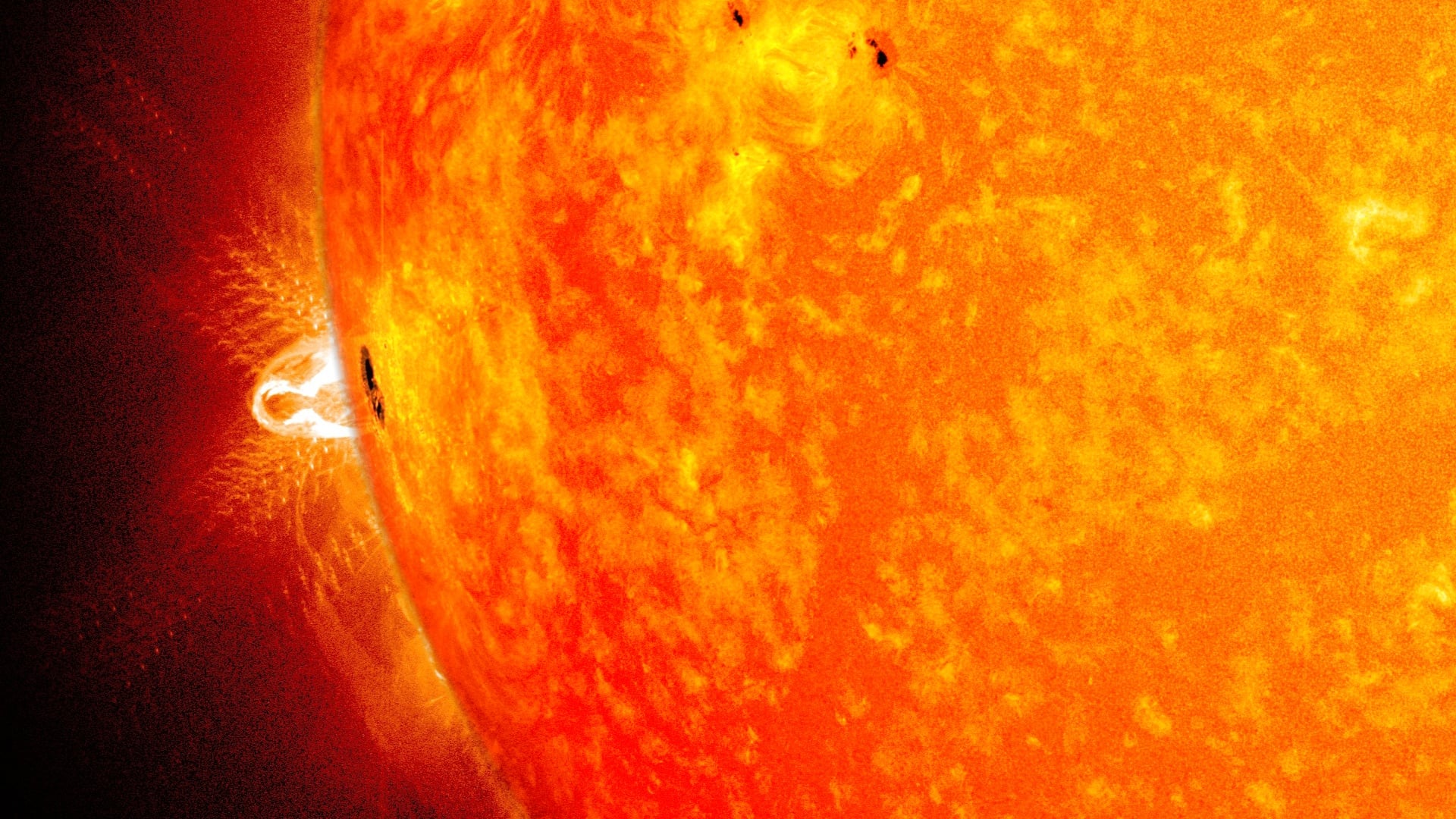

The Sun is not only our closest stellar neighbor, it’s also the star we understand the most. As we’ve observed it over the centuries, we’ve learned that the Sun is not an immortal constant. It goes through active and quiet cycles, it has…

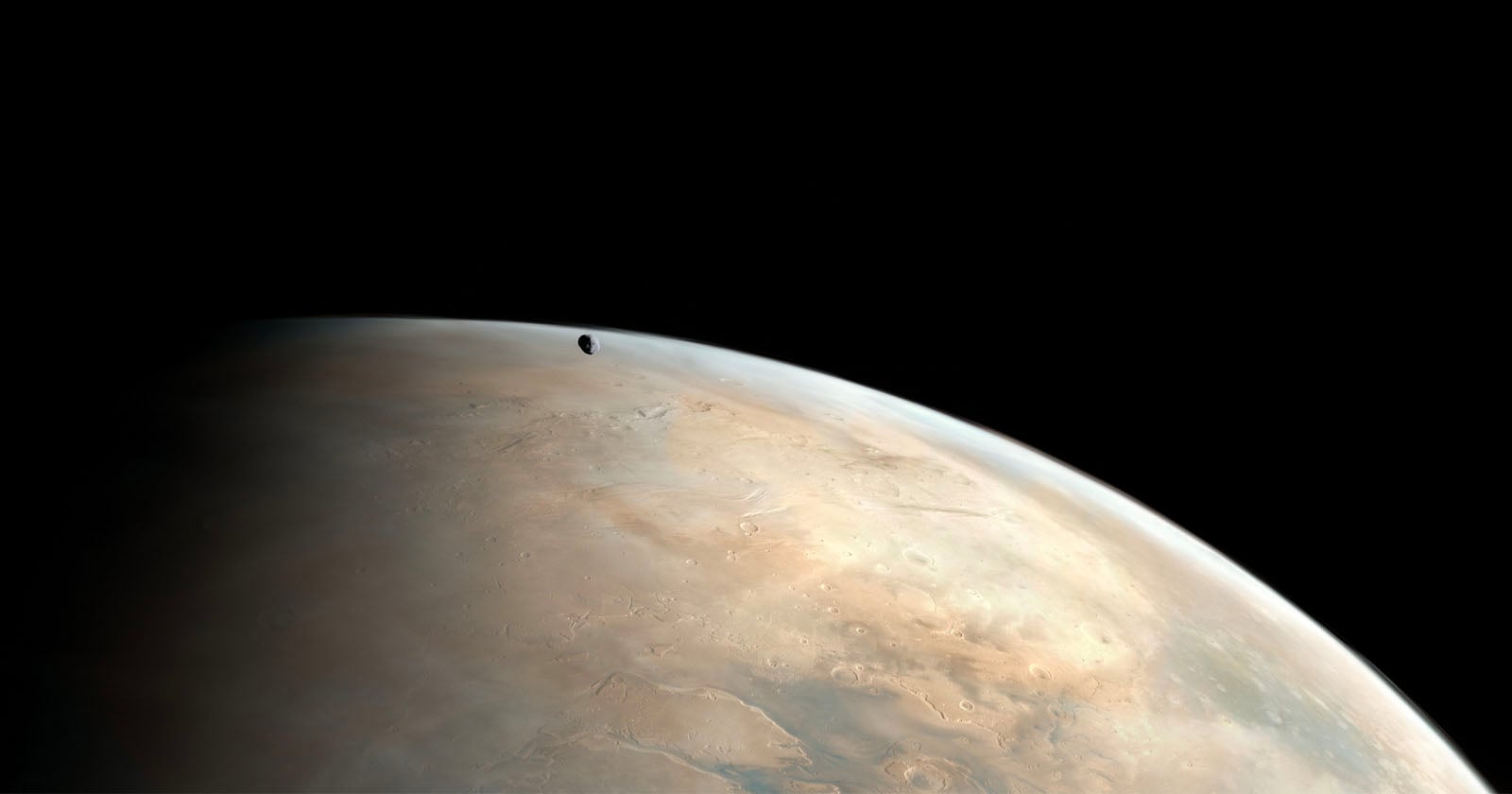

Rogue planets — worlds that drift through space alone without a star — largely remain a mystery to scientists. Now, astronomers have for the first time confirmed the existence of one of these starless worlds by pinpointing its distance and…

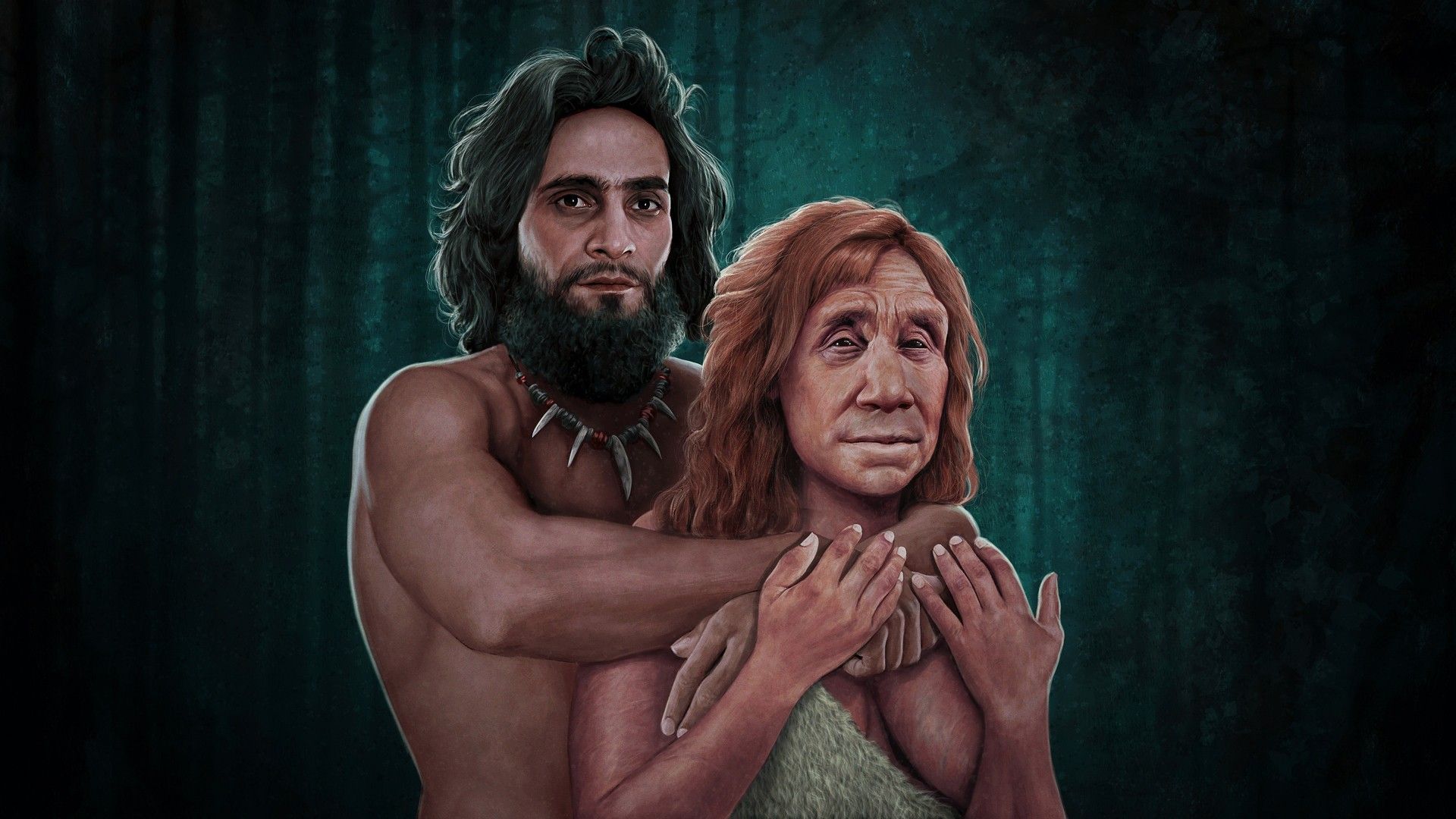

The group had traveled for thousands of miles, crossing Africa and the Middle East until finally reaching the dimly lit forests of the new continent. They were long-vanished members of our modern human tribe, and among the first Homo sapiens to…

Newly-released photos by…

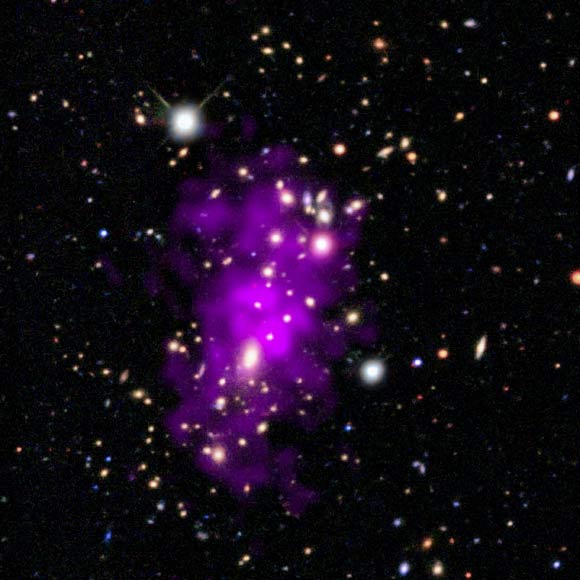

Astronomers discovered an enormous galaxy cluster called RM J130558.9+263048.4 on December 31, 2020; the date, combined with the bubble-like appearance of the galaxies and the superheated gas, inspired the astronomers to nickname the object the…

An elusive meteor shower kicks off the skywatching year for 2026.

It sneaks up on us, every annual flip of the calendar into the new year. If skies are clear, keep an eye out for the brief but strong Quadrantid meteors this weekend.

The…

All terrestrial vertebrates owe their existence to that unlikely moment 350-odd million years ago when an ancestral species of fish hauled itself out of the water. But perhaps the real surprise is that it happened only once, says Stuart…