NEW YORK (AP) — The year’s first supermoon and meteor shower will sync up in January skies, but the light from one may dim the other.

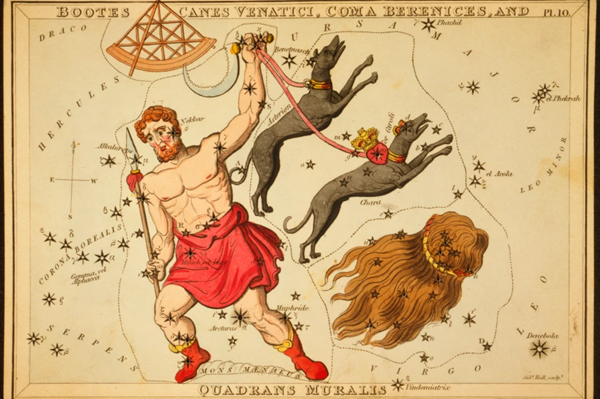

The Quadrantid meteor shower peaks Friday night into Saturday morning, according to the American…

NEW YORK (AP) — The year’s first supermoon and meteor shower will sync up in January skies, but the light from one may dim the other.

The Quadrantid meteor shower peaks Friday night into Saturday morning, according to the American…

A groundbreaking study led by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology revealed critical new details about one of the ocean’s most abundant life forms — SAR11 marine bacteria.

Understanding these…

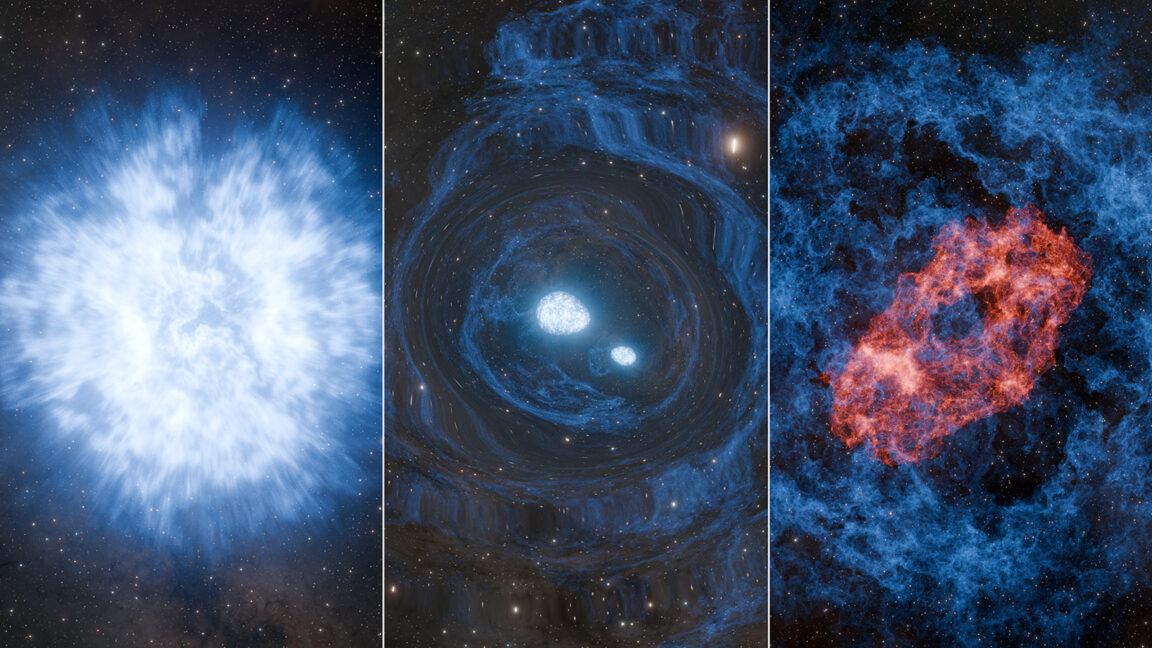

Supernovae are the spectacular explosions that result from dying massive stars, seeding the universe with heavy elements like carbon and iron. Kilonovae occur when two binary neutron stars begin circling into their death…

When 3I/ATLAS swept past the Sun in late October 2025, it became only the third confirmed visitor from interstellar space ever detected. Unlike the mysterious ‘Oumuamua, which revealed almost nothing about itself during its brief flyby…

A new peer-reviewed study led by Israeli researchers has found that coral reefs help control the daily lives of microbes, tiny bacteria, and microscopic algae that live in the water around them.

The researchers believe that as climate…

LONDION – Bright full moons, dazzling meteor shower displays and remarkable total eclipses will give stargazers plenty of reasons to look to the sky in 2026. The new year kicks off with the full wolf moon on Saturday, the first of three…

A SpaceX rocket’s launch to deliver an Italian satellite into orbit has been rescheduled for Friday evening at Vandenberg Space Force Base after being delayed several days by technical troubles involving ground support equipment….