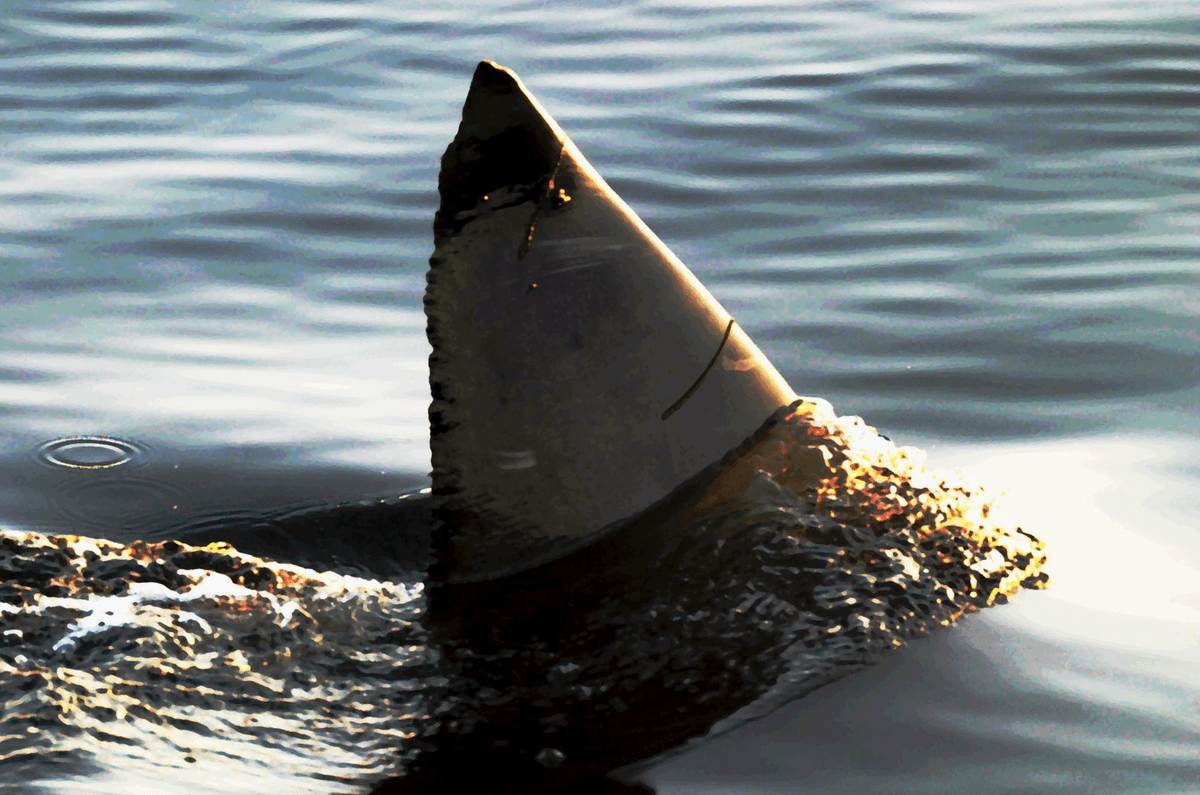

If great white shark swimming into a pond sounds like something out of a movie, that’s because it is, says Greg Skomal. Remember the infamous scene in Jaws where the shark swims into a pond, just where people thought they would be safe?…

Category: 7. Science

-

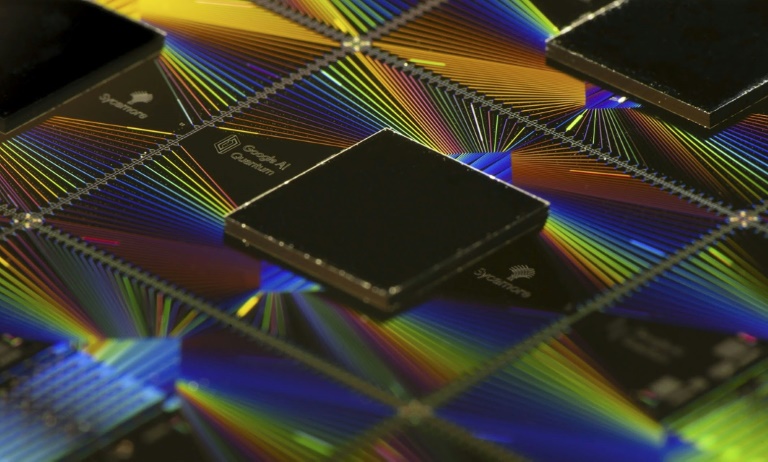

Quantum computing: Tracking qubit fluctuations in real time

Quantum computing has been touted as a revolutionary advance that uses our growing scientific understanding of the subatomic world to create a machine with powers far beyond those of conventional computers – Copyright AFP/File LUCA SOLA

Qubits…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists Simulated The Big Bang’s Aftermath, And Found The Universe Was Like Soup : ScienceAlert

Immediately after the Big Bang boomed, the Universe was a trillion-degree ‘soup’ of unimaginably dense plasma. In a breakthrough experiment, researchers have found the first evidence that this exotic primordial goo did actually slosh and…

Continue Reading

-

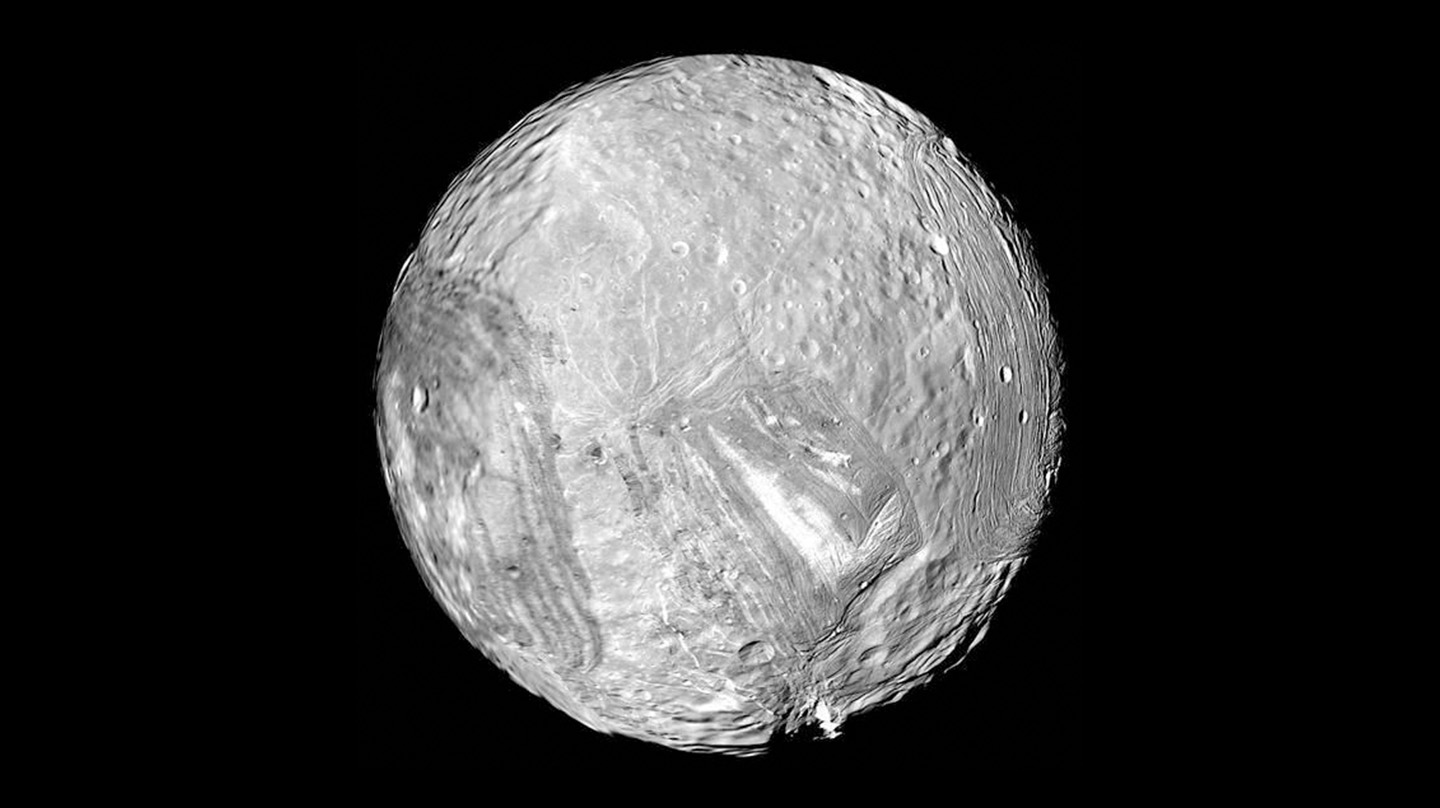

Miranda’s Unlikely Ocean Has Us Asking If There’s Life Clinging On Around Uranus

If you’re interested in extraterrestrial life, these past few years have given an embarrassment of places to look, even in our own solar system. Mars has been an obvious choice since before the Space Age; in the orbit of Jupiter,…

Continue Reading

-

NASA blast Boeing and reveal exactly what they think was to blame after astronauts were stranded in space for months

A report from NASA has slammed the failure of a Starliner which left two astronauts stranded in space as a ‘Type A’ error.

This category is the worst that an incident can be placed in, and puts it in the same grouping as fatal shuttle disasters.

Continue Reading

-

Webb Reveals Hidden Layers of Uranus’ Upper Atmosphere

For the first time, astronomers have mapped the vertical structure of Uranus’ ionosphere, uncovering unexpected temperature peaks, weakened ion densities, and puzzling dark regions shaped by the planet’s extreme magnetic field. The…

Continue Reading

-

Antarctic drilling peers deep into ice shelf's past – Phys.org

- Antarctic drilling peers deep into ice shelf’s past Phys.org

- Record-breaking sediment core may help predict Antarctic ice loss ETH Zürich

- Mud beneath Antarctic ice reveals millions of years of ice retreat Earth.com

- Team of scientists retrieve…

Continue Reading

-

Early life adversity impairs visually evoked innate defensive behaviors via oxytocin signaling

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Advers. Child. Exp. Study Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258 (1998).

Continue Reading

-

Remote volcano wakes up after being dormant for 700,000 years

A volcano in southeastern Iran has nudged upward by about 3.5 inches (9 centimeters) in 10 months. This might sound like a small rise but it has big significance.

A new study used satellite data to spot the change and argues that pressure is…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists Suggest That Igniting Oil Spills to Create Fire Tornadoes Might Actually Be Good for the Oceans

Illustration by Tag Hartman-Simkins / Futurism. Source: Getty Images When you think of saving our oceans, what comes to mind? Maybe you think about reef restoration techniques like coral transplantation, or making…

Continue Reading