|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

Category: 7. Science

-

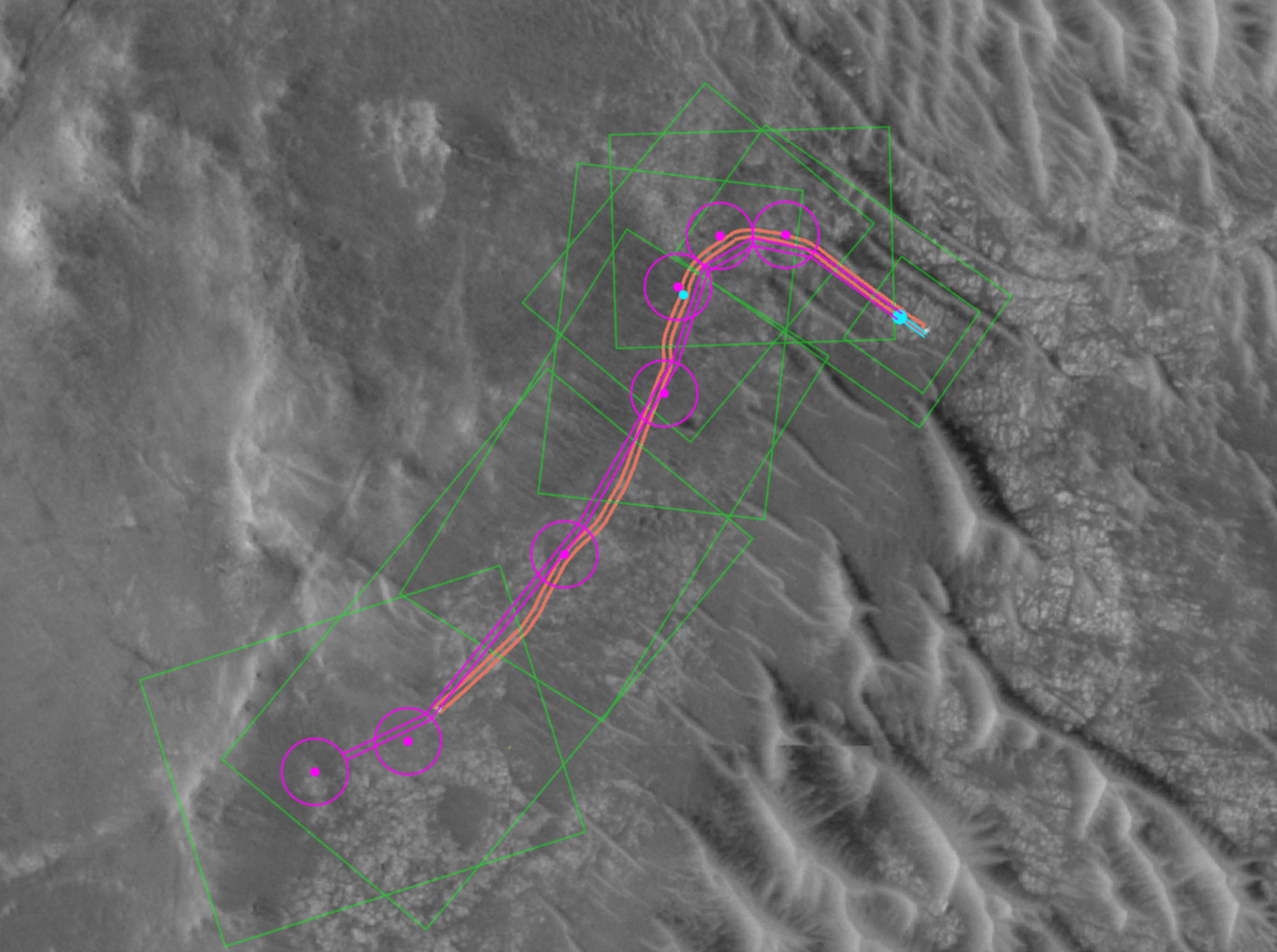

NASA uses Claude to plan first AI rover drives on Mars

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has completed the first rover drives on another world planned by artificial intelligence, marking a shift in how mission-critical navigation decisions can be made beyond Earth.

On December eight and ten,…

Continue Reading

-

Axiom Space selected for Fifth Private Mission to Space Station

NASA has awarded Axiom Space its fifth private astronaut mission to the International Space Station, reinforcing the accelerating shift toward commercial participation in low Earth orbit as the agency prepares for deeper space exploration.

The…

Continue Reading

-

From field to screen: the changing landscape of ecology research

For centuries, ecology and biology have been built on muddy boots, mosquito bites and long days spent in forests, wetlands and oceans. Fieldwork was not just a method; it was an identity. To be an ecologist meant to be outdoors, immersed in…

Continue Reading

-

Web-based tool makes it easier to design advanced materials

TSUKUBA, Japan, Feb 2, 2026 – (ACN Newswire) – Modern industry relies heavily on catalysts, which are substances that speed up chemical reactions. They’re vital in everything from manufacturing household chemicals to generating…

Continue Reading

-

How to Capture the February 2026 Snow Moon on iPhone – The Mac Observer

- How to Capture the February 2026 Snow Moon on iPhone The Mac Observer

- See February’s full snow moon light up the sky CNN

- Snow Moon 2026: When and where to see February’s full moon in the UK tonight North Wales Live

- February’s Snow Full Moon…

Continue Reading

-

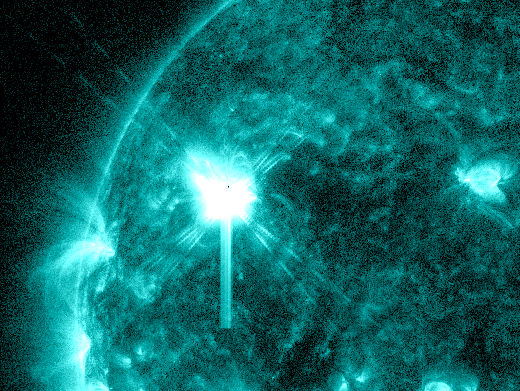

Major Solar Flare Strikes as Giant New Sunspot Erupts

A sunspot that didn’t exist at the beginning of the weekend has since grown into a vast and active region, and it hasn’t taken long to make itself known. The new arrival has already produced a powerful solar flare, one that lingered rather…

Continue Reading

-

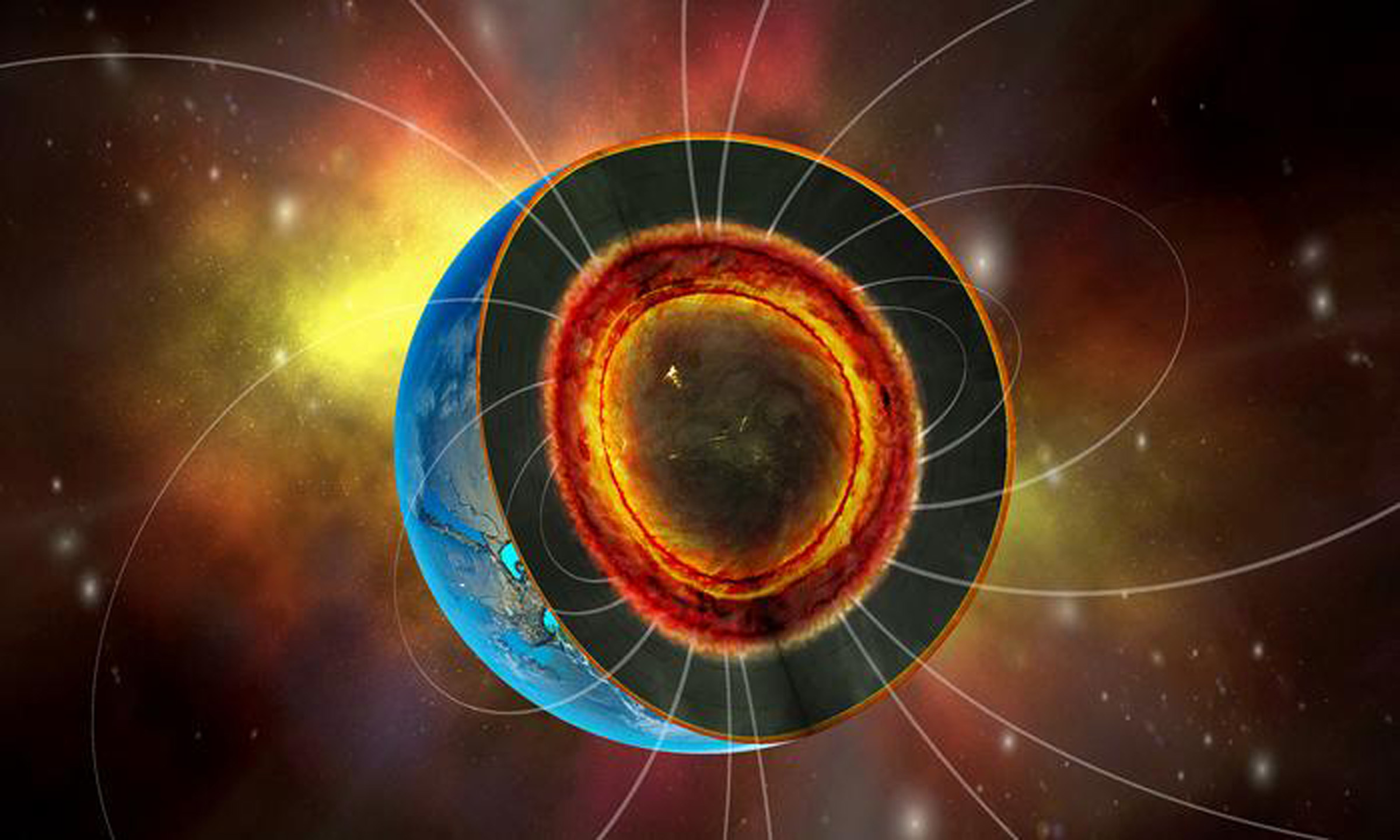

Molten rock deep inside planets may decide their chances for life

Deep layers of molten rock inside large rocky planets have been shown to generate magnetic fields strong enough to persist for billions of years.

Such long-lived shields can decide whether a planet holds onto its atmosphere or is slowly stripped…

Continue Reading

-

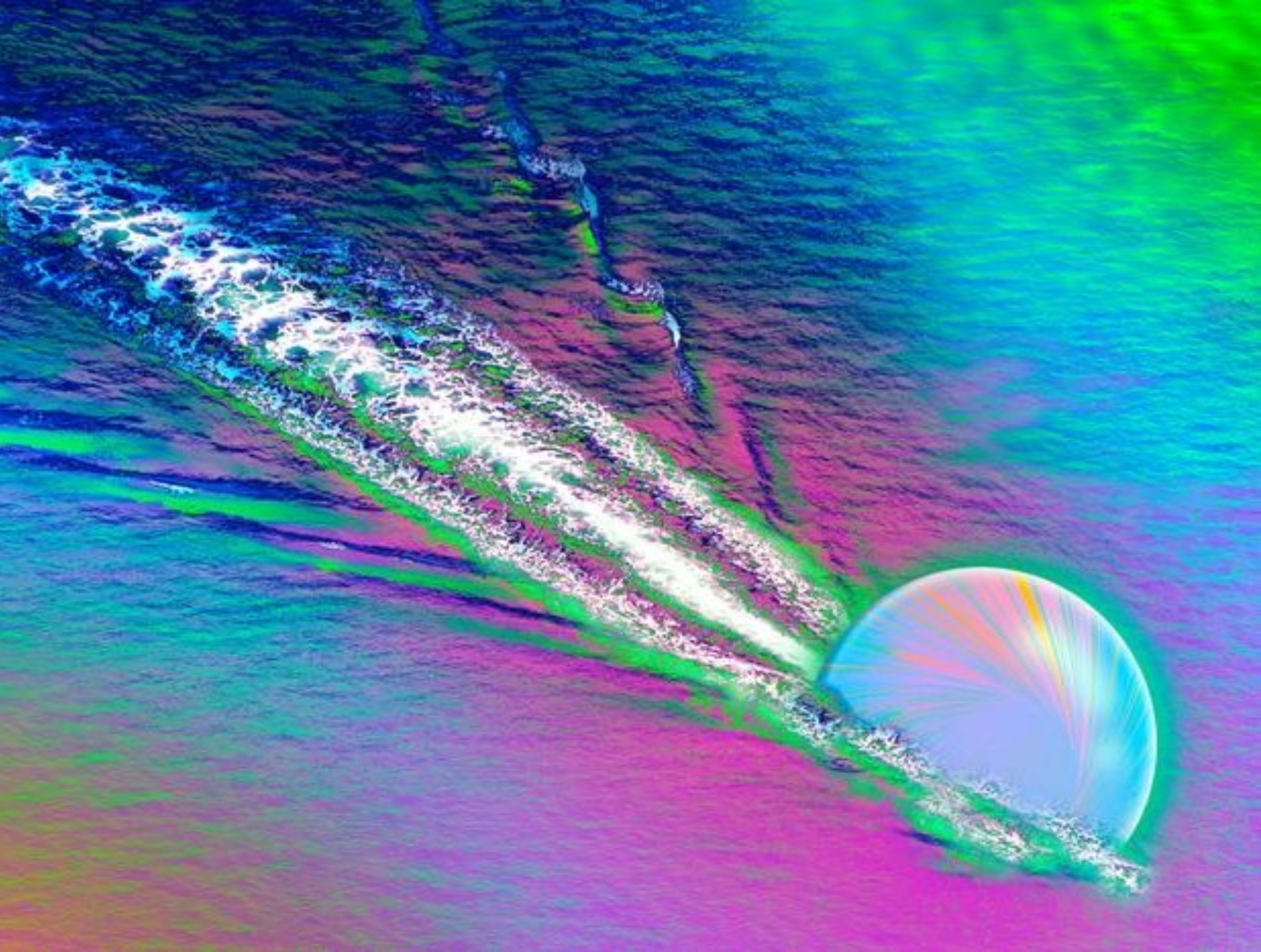

It’s the size of 3 Central Parks in New York, could be 8,650 years old – and glows in the dark. Forget the blue whale this beast is the world’s biggest organism

If you ever want to pull out the big guns in a pub quiz, then do I have a fact for you! Contrary to popular belief, the biggest organism in the world is not the blue whale. Nor is it the giant sequoia. Nor is it the extinct and admittedly…

Continue Reading

-

‘Soupy’ matter flowed through the early universe

Right after the universe began, nothing looked familiar. Space was packed with heat and motion. Matter had not yet settled into atoms or even protons.

Instead, everything existed in a frantic state made of the smallest building blocks, racing…

Continue Reading