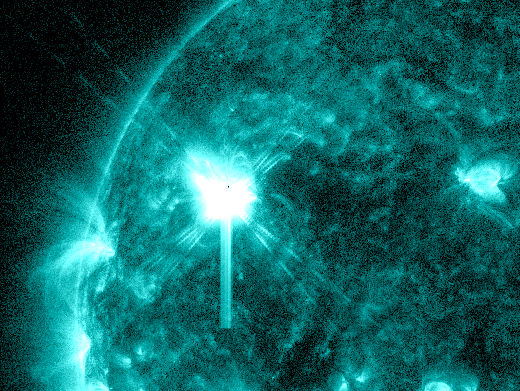

A sunspot that didn’t exist at the beginning of the weekend has since grown into a vast and active region, and it hasn’t taken long to make itself known. The new arrival has already produced a powerful solar flare, one that lingered rather…

Category: 7. Science

-

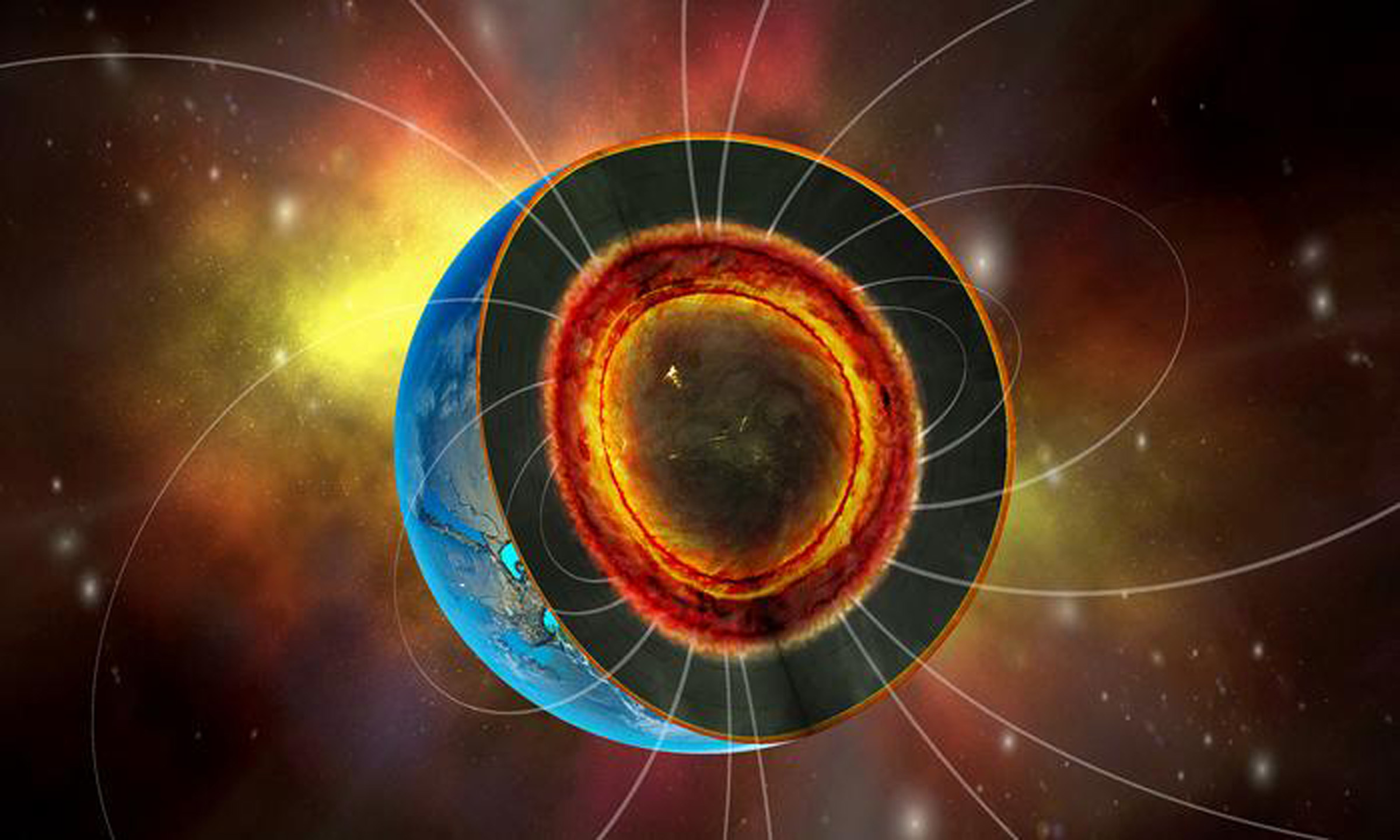

Molten rock deep inside planets may decide their chances for life

Deep layers of molten rock inside large rocky planets have been shown to generate magnetic fields strong enough to persist for billions of years.

Such long-lived shields can decide whether a planet holds onto its atmosphere or is slowly stripped…

Continue Reading

-

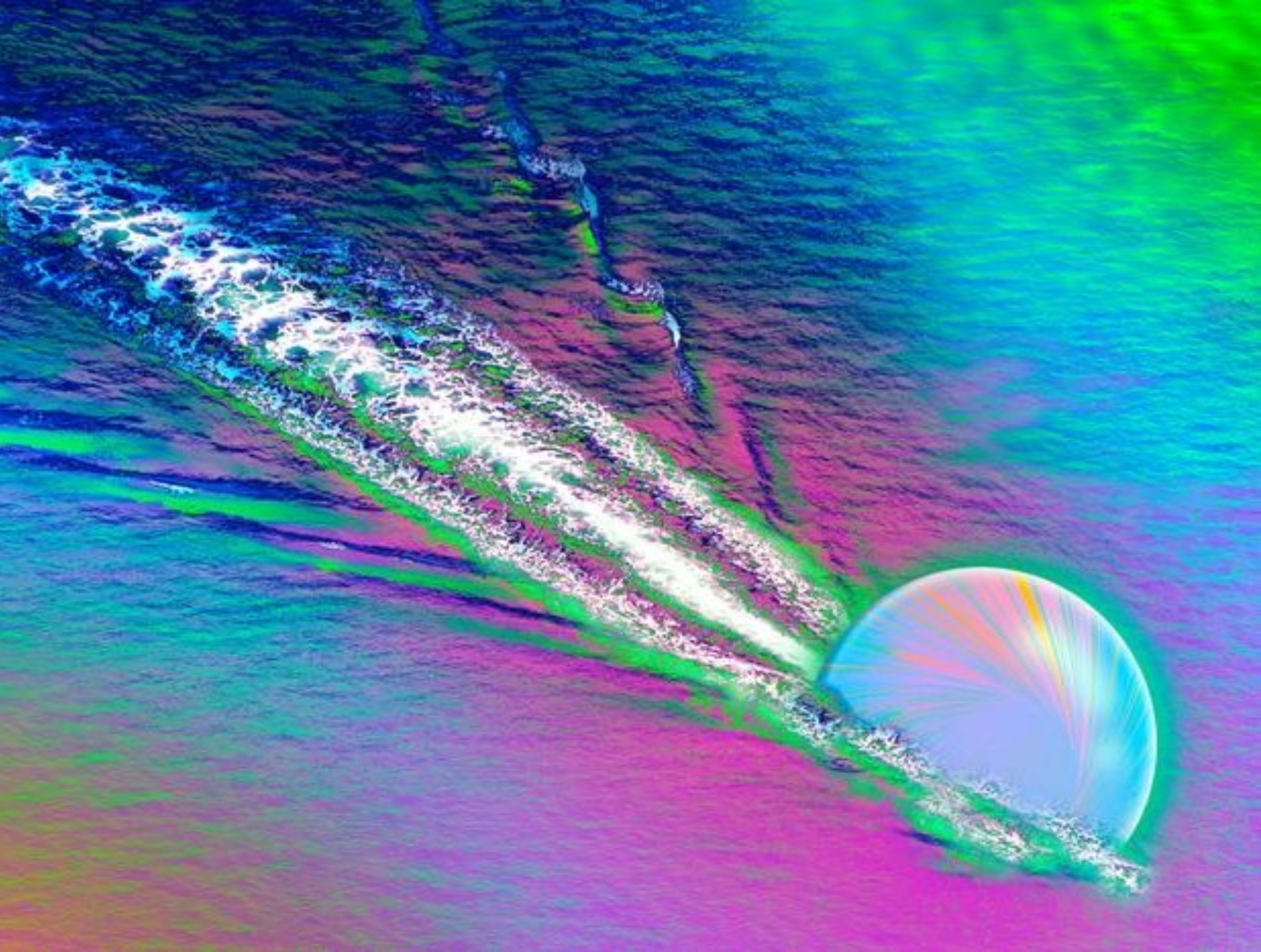

It’s the size of 3 Central Parks in New York, could be 8,650 years old – and glows in the dark. Forget the blue whale this beast is the world’s biggest organism

If you ever want to pull out the big guns in a pub quiz, then do I have a fact for you! Contrary to popular belief, the biggest organism in the world is not the blue whale. Nor is it the giant sequoia. Nor is it the extinct and admittedly…

Continue Reading

-

‘Soupy’ matter flowed through the early universe

Right after the universe began, nothing looked familiar. Space was packed with heat and motion. Matter had not yet settled into atoms or even protons.

Instead, everything existed in a frantic state made of the smallest building blocks, racing…

Continue Reading

-

Full-parametric, transdimensional, and joint inversion of surface wave dispersion and earthquake-based HVSR by MBMO for obtaining reliable subsurface structures

Nakamura, Y. A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. Q. Rep. 30, 25–33 (1989).

Aki, K. Space and time spectra of stationary…

Continue Reading

-

Catch a falling star: cosmic dust may reveal how life began, and a Sydney lab is making it from scratch | Astronomy

How does one acquire star dust? One option, as the Perry Como song suggests, is to catch a falling star and put it in your pocket, so to speak.

Thousands of tonnes of cosmic dust bombard the Earth each year, mostly vaporising in the atmosphere….

Continue Reading

-

250-Million-Year-Old Fossil Reveals Origins of Our Unique Hearing : ScienceAlert

Modern mammals have unique hearing abilities, able to sense a broad range of volumes and frequencies using middle-ear features, including our eardrums and a few small bones.

A new study from paleontologists at the University of Chicago in the…

Continue Reading

-

Huayuan biota decodes Earth's first Phanerozoic mass extinction – Phys.org

- Huayuan biota decodes Earth’s first Phanerozoic mass extinction Phys.org

- A Cambrian soft-bodied biota after the first Phanerozoic mass extinction Nature

- A 512-Million-Year-Old Fossil Site in China Reveals Strange Sea Creatures From an Ancient…

Continue Reading

-

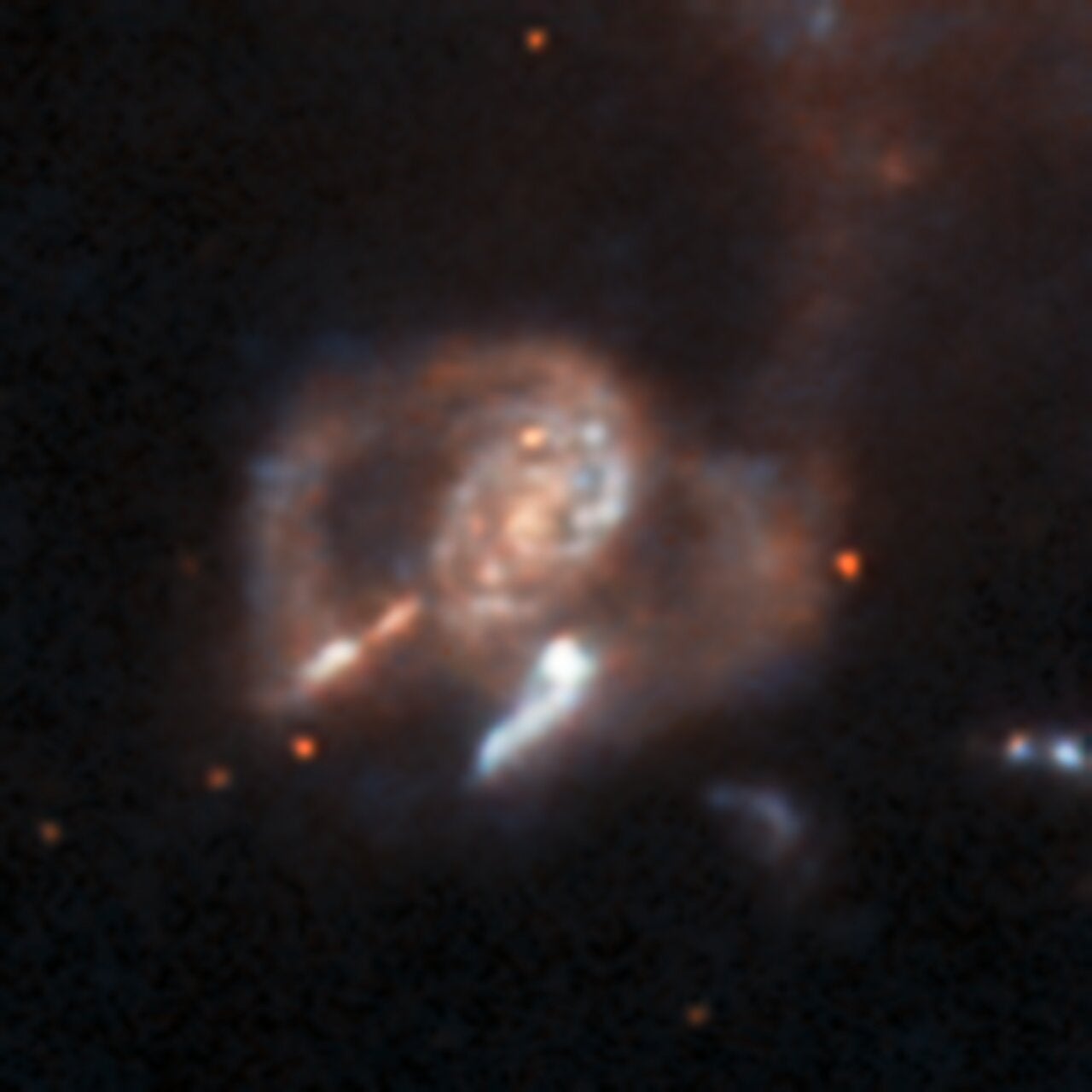

AI Tool Uncovers Hundreds of Hidden Cosmic Oddities in Hubble Data

A team of astronomers based at the European Space Agency demonstrated how artificial intelligence technology will alter existing methods of locating rare astronomical phenomena within our galaxy, the Milky Way, and beyond. David O’Ryan and Pablo…

Continue Reading

-

DNA helps solve the mystery of the Beachy Head Woman

In a quiet basement in southern England, a cardboard box containing the skeleton of a young woman remained undisturbed for decades. She lived in Roman times.

There was no name or record of her burial – only a scribbled note saying that she was…

Continue Reading