Category: 7. Science

-

Remarkable Fossil from South Africa May Be New Species of Australopithecus: Study

New research led by scientists from the University of Cambridge and Latrobe University challenges the classification of the Little Foot fossil as Australopithecus prometheus.

The Little Foot fossil in the Sterkfontein cave, central South…

Continue Reading

-

A Single Solar Storm Could Trigger an End to Space Travel. Here’s How. : ScienceAlert

A “house of cards” is such a wonderful English phrase, one now primarily associated with a Netflix political drama. However, its original meaning refers to a fundamentally unstable system.

It’s also the term Sarah Thiele, originally a PhD…

Continue Reading

-

Stay up late tonight to watch Europe’s Ariane 6 rocket launch its 1st pair of Galileo navigation satellites

Vol VA266 | Galileo L14 | Ariane 6 | Arianespace – YouTube

Watch OnEurope’s towering Ariane 6 rocket is gaining momentum in the heavy-lift launch market as the vehicle gears up for its fifth flight.

Continue Reading

-

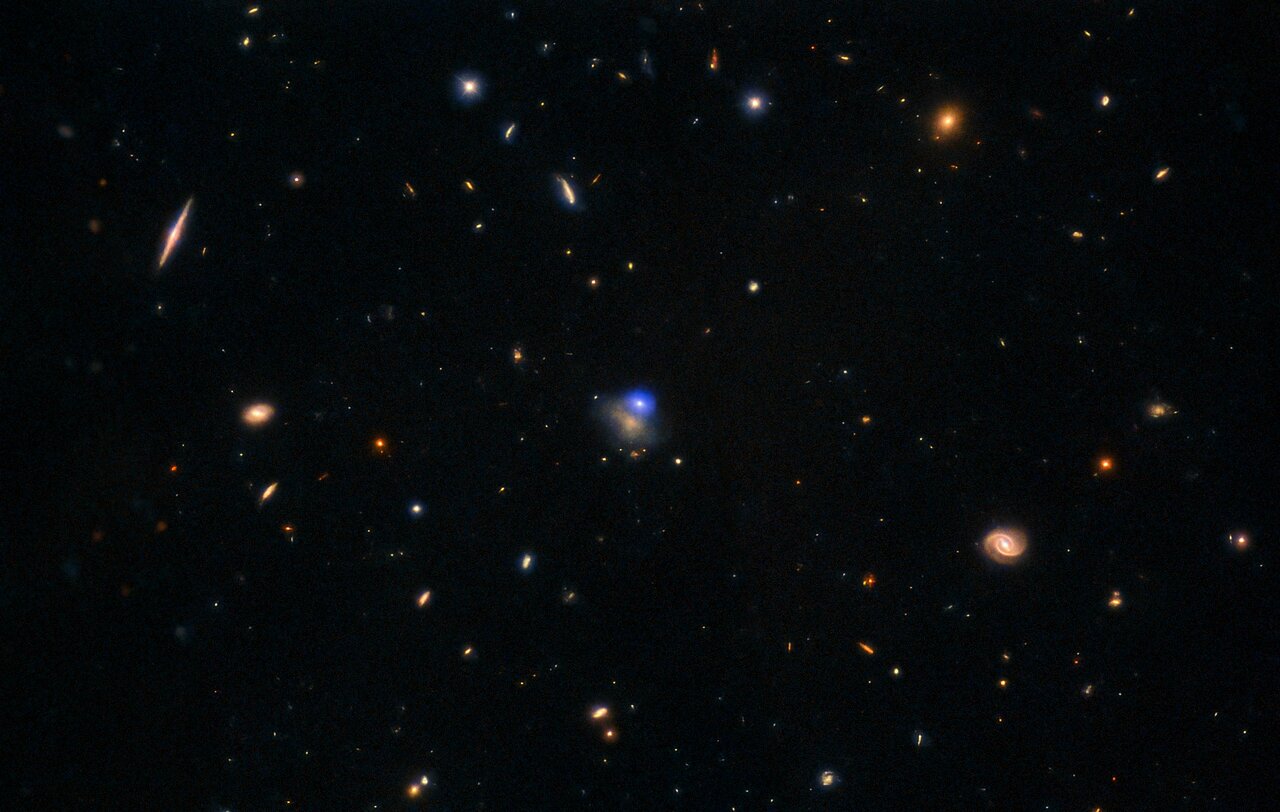

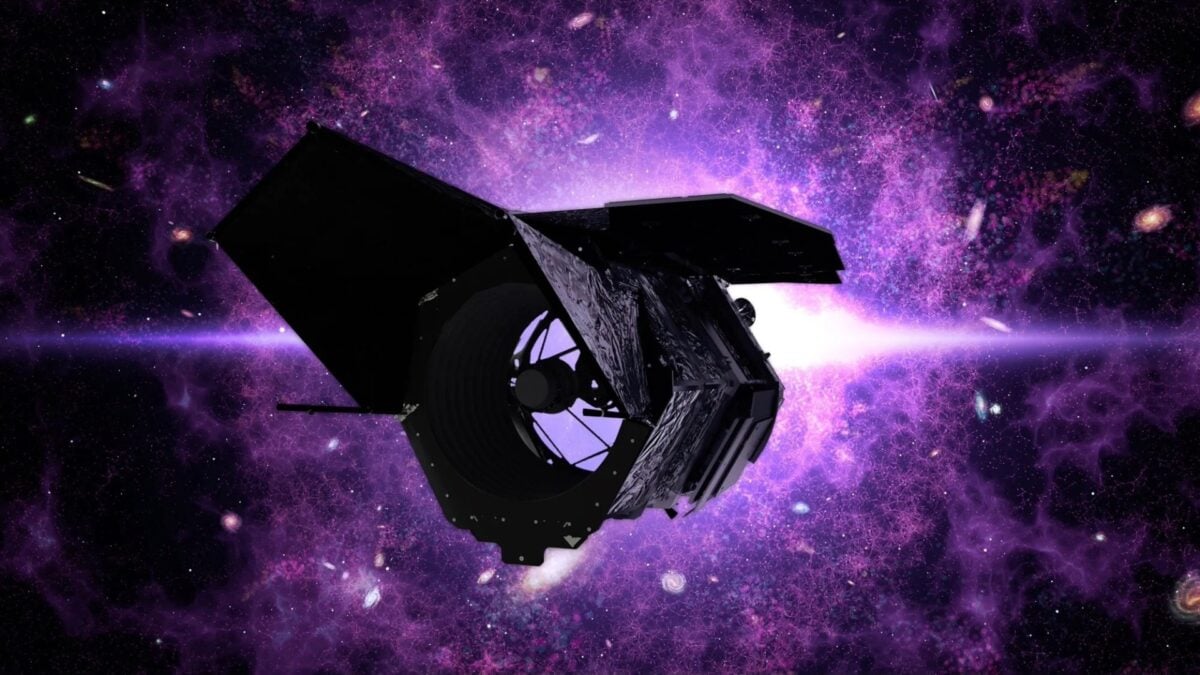

Why NASA’s New $4 Billion Telescope Will Stare at Absolutely Nothing

Earlier this year, leaked budget cuts cast a dark shadow over the future of NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope—a multi-billion-dollar instrument with the capacity of “200 Hubbles,” according to experts. Thankfully,…

Continue Reading

-

National Parks to Visit in 2026: Great Barrier Reef, Australia

In 2024, the reef experienced its most widespread coral-bleaching event on record, affecting the entire reef system. By 2025, surveys by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) documented the largest annual drop in live coral…

Continue Reading

-

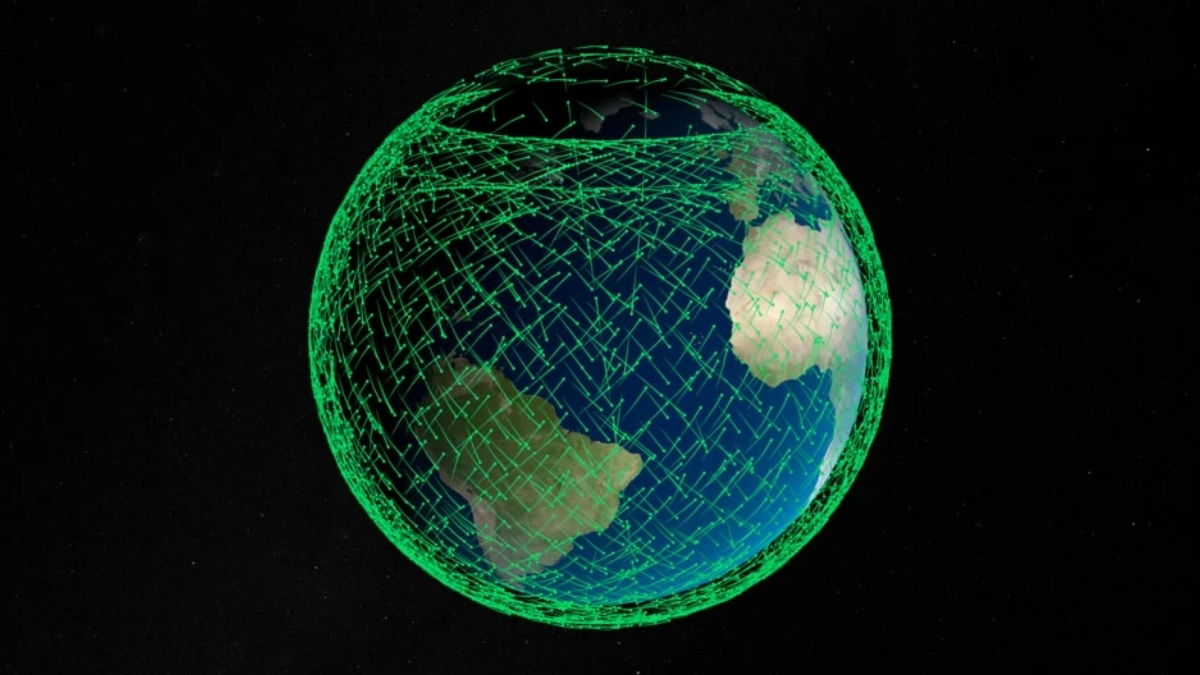

ULA lifts 27 Amazon satellites on Atlas V rocket

United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket pictured in June lifting off from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Cape Canaveral, Fla. ULA launched its Atlas V rocket fitted with 27 more Amazon Leo satellites for its…Continue Reading

-

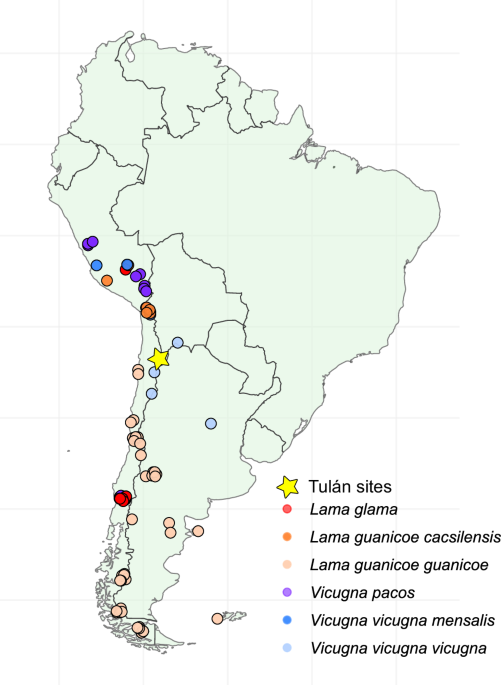

Palaeogenomics suggest domesticated camelid herding and wild camelid hunting in early pastoralist societies in the Atacama Desert

Permits and permissions

All research was conducted in accordance with Chilean regulations. Excavation permits were issued by the Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales de Chile (CMN) under permit N° 4409 (18.11.2013). Export of osteological samples…

Continue Reading

-

Watch Japanese H3 rocket launch Michibiki 5 navigation satellite tonight

準天頂衛星システム「みちびき5号機」 /H3ロケット8号機打上げライブ中継 – YouTube

Watch OnJapan will launch a new navigation satellite to orbit tonight (Dec. 16), and you can watch the action live.

Continue Reading