The discovery came after an international team of paleontologists, including researchers from Penn State and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, re-examined fossils that had been found in the region back in 1916. Their findings, published…

Category: 7. Science

-

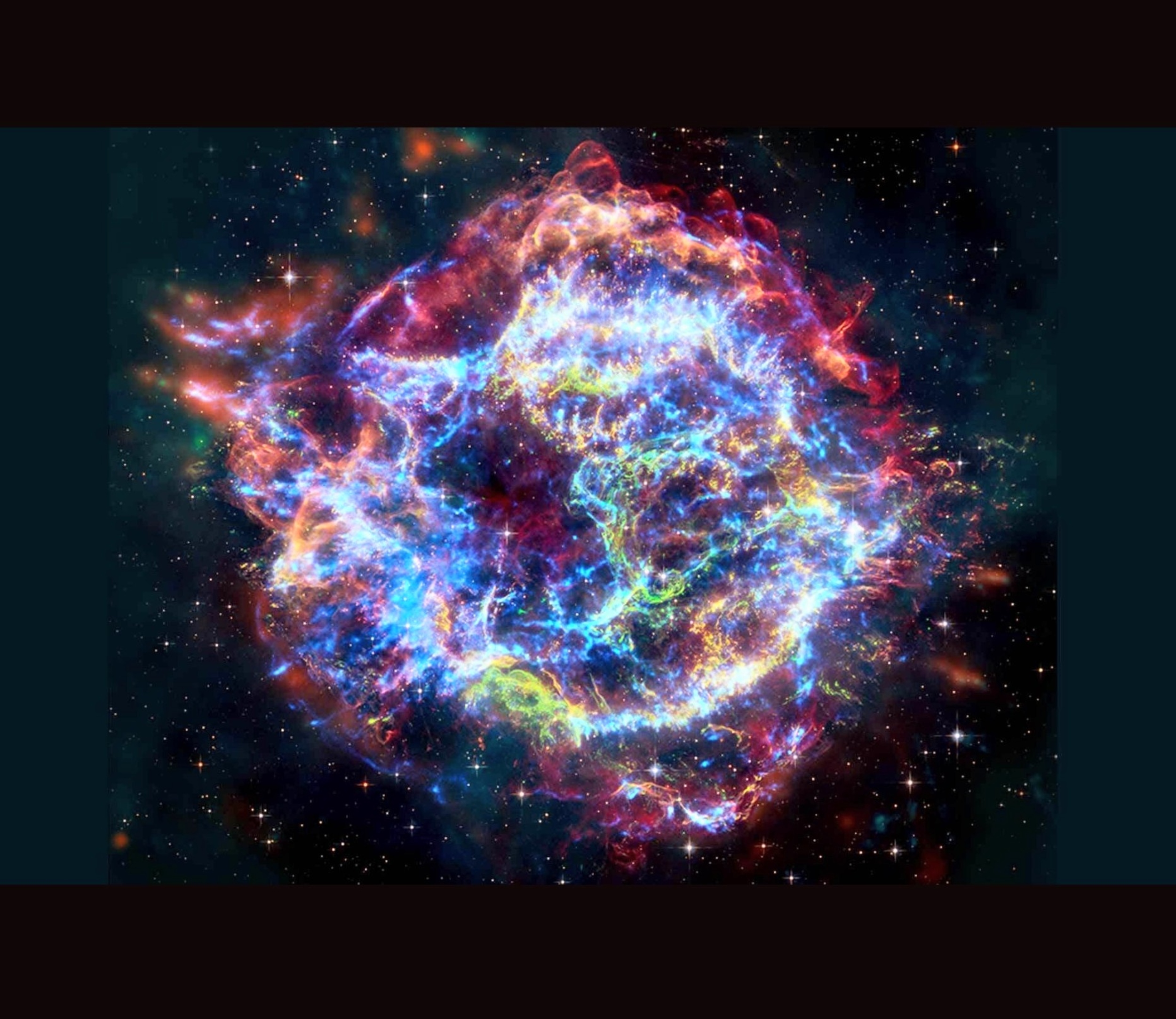

Life’s ingredients found in the ashes of an exploded star

Astronomers used Japan’s XRISM spacecraft to detect clear X-ray signatures of chlorine and potassium in the debris of a well-known supernova. Potassium appears in the data with extremely high confidence, exceeding the 6-sigma level.

The signals…

Continue Reading

-

Strangely bleached rocks on Mars hint that the Red Planet was once a tropical oasis

Mars was once home to wet, humid areas that received heavy rainfall, similar to tropical regions on Earth, a new study of unusually bleached rocks suggests.

Researchers were intrigued by peculiar light-colored rocks that NASA’s Perseverance rover…

Continue Reading

-

The interaction of 2D vortices in a developing pulsed plasma jet

Moreau, E. Airflow control by non-thermal plasma actuators. J. Phys. D. 40, 605–636 (2007).

Corke, T. C., Enloe, C. L. & Wilkinson, S. P. Dielectric barrier discharge plasma actuators for…

Continue Reading

-

New cosmic lensing test sharpens the Hubble tension and hints at new physics

For more than a decade, cosmology has been stuck with a puzzling contradiction. Two of the most trusted ways of measuring the universe’s expansion give two different answers.

One set of measurements, based on nearby stars and exploding…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists sent a menstrual cup to space. This is how it went

What can you do if you get your period in space? Scientists are making that question a little easier to answer by testing how well a menstrual cup, a popular reusable period product, holds up against the pressures of space flight.

In 2022, a…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists sent a menstrual cup to space. This is how it went

When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

This experiment could help make space more comfortable and accessible to female astronauts. . | Credit: Westend61/Getty Images

What can you do if…

Continue Reading

-

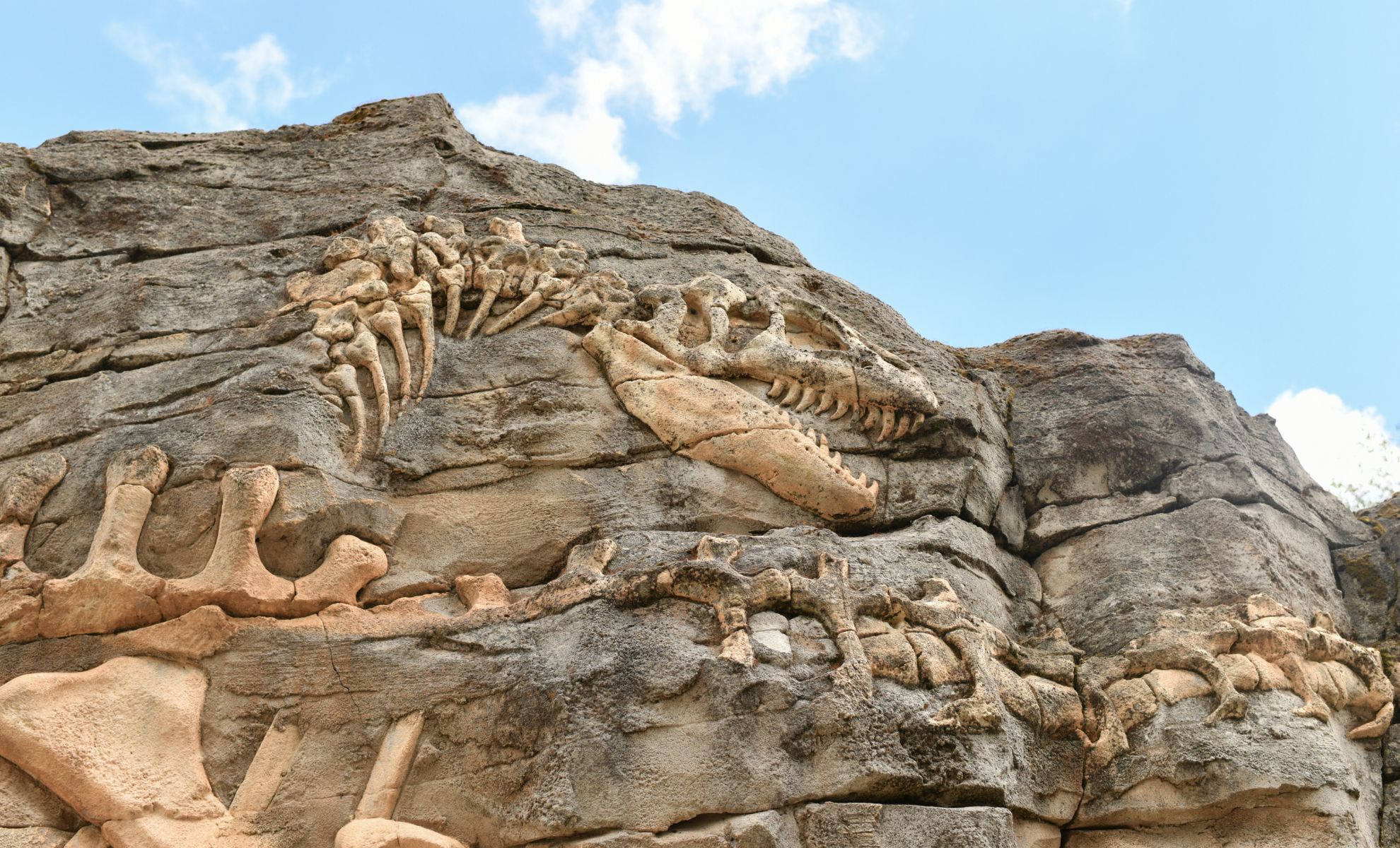

Two ancient cousins of Lucy walked on two legs in different ways

On the ancient plains of Ethiopia, early human relatives were already trying out different ways of being upright. If you grew up hearing about Lucy as the main star of that era, new fossil finds invite you to picture a busier scene, with at least…

Continue Reading

-

11 Star Parties For Next Weekend’s Geminid Meteor Shower Peak

On Saturday, Dec. 13, the Geminid meteor shower will peak.

getty

One of the strongest meteor showers of the year is about to peak during a period of heightened activity for the Northern Lights, but is your night sky dark enough for the rare…

Continue Reading

-

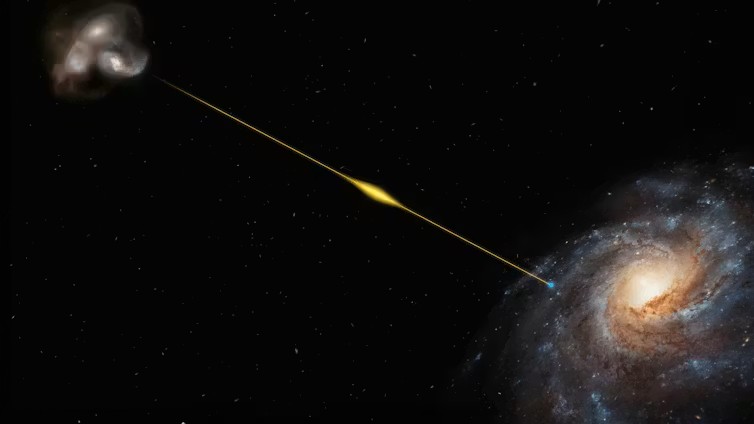

Where’s the normal matter in our universe?

Mysterious blasts of radio waves from across the universe called fast radio bursts help astronomers catalog the whereabouts of normal matter in our universe. Image via ESO/ M. Kornmesser/ The Conversation (CC BY-SA). The 2026 EarthSky lunar…

Continue Reading