The quest to unify quantum mechanics and gravity stands as one of the most profound challenges in modern physics. For decades, these two pillars of science have remained irreconcilable: quantum mechanics governs the behavior of particles at…

Category: 7. Science

-

Asteroid loaded with amino acids offers new clues about the origin of life on Earth – Phys.org

- Asteroid loaded with amino acids offers new clues about the origin of life on Earth Phys.org

- Scientists found tryptophan, the ‘sleepy’ amino acid, in an asteroid. Here’s what it means CNN

- ‘Jigsaw piece’: Bennu reaffirms asteroids sowed…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists may have found dark matter after 100 years of searching

In the early 1930s, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky noticed that many galaxies were moving far faster than their visible mass should permit. This unusual motion led him to propose that some kind of invisible structure — dark matter — was…

Continue Reading

-

Scientists may have found dark matter after 100 years of searching

In the early 1930s, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky noticed that many galaxies were moving far faster than their visible mass should permit. This unusual motion led him to propose that some kind of invisible structure — dark matter — was…

Continue Reading

-

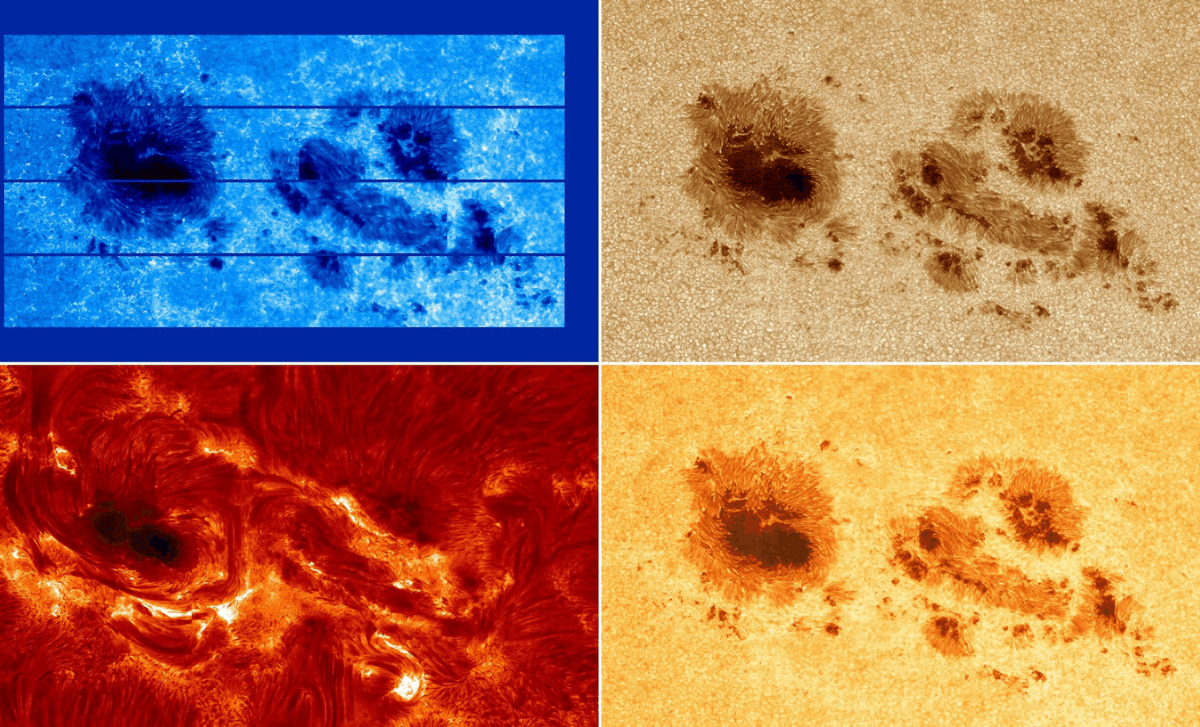

Scientists Capture Rare, High-Resolution Solar Flares in Unprecedented Detail

In an exciting breakthrough, scientists have captured a rare, high-resolution glimpse into one of the most active solar regions that has been producing powerful X-class solar flares. These flares, some of the most intense solar events, offer…

Continue Reading

-

Novel characterisation of microplastics and other contaminant particles using new scanning electron microscopy technologies

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3(7), e1700782. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700782 (2017).

Trestrail, C., Nugegoda, D….

Continue Reading

-

Get one of the best star projectors for its lowest-ever price this Black Friday weekend

One of the best star projectors and now one of the best star projector Black Friday deals, you can save 20% on the Hommkiety Galaxy Projector. Normally retailing at $40, this Black Friday weekend sees it drop in price to $31.99 — making it the…

Continue Reading

-

Northern Italian town sees unusual red halo again as experts link it to powerful lightning event

People in the small town of Possagno in northern Italy were taken aback by the sight of a red halo-like ring hovering above their town on November 17. Interestingly, this is not the first time that such a phenomenon has been observed in this…

Continue Reading

-

“No One Has Really Gone Back and Looked at What the Bones Themselves Say”: New Research is Shedding Light on an Ancient Sea Monster

Ohio’s ancient sea monster, the Dunkleosteus terrelli, is revealed in new clarity by a recent study that shows just how strange the creature truly was.

Researchers from Case Western University led the work, which…

Continue Reading

-

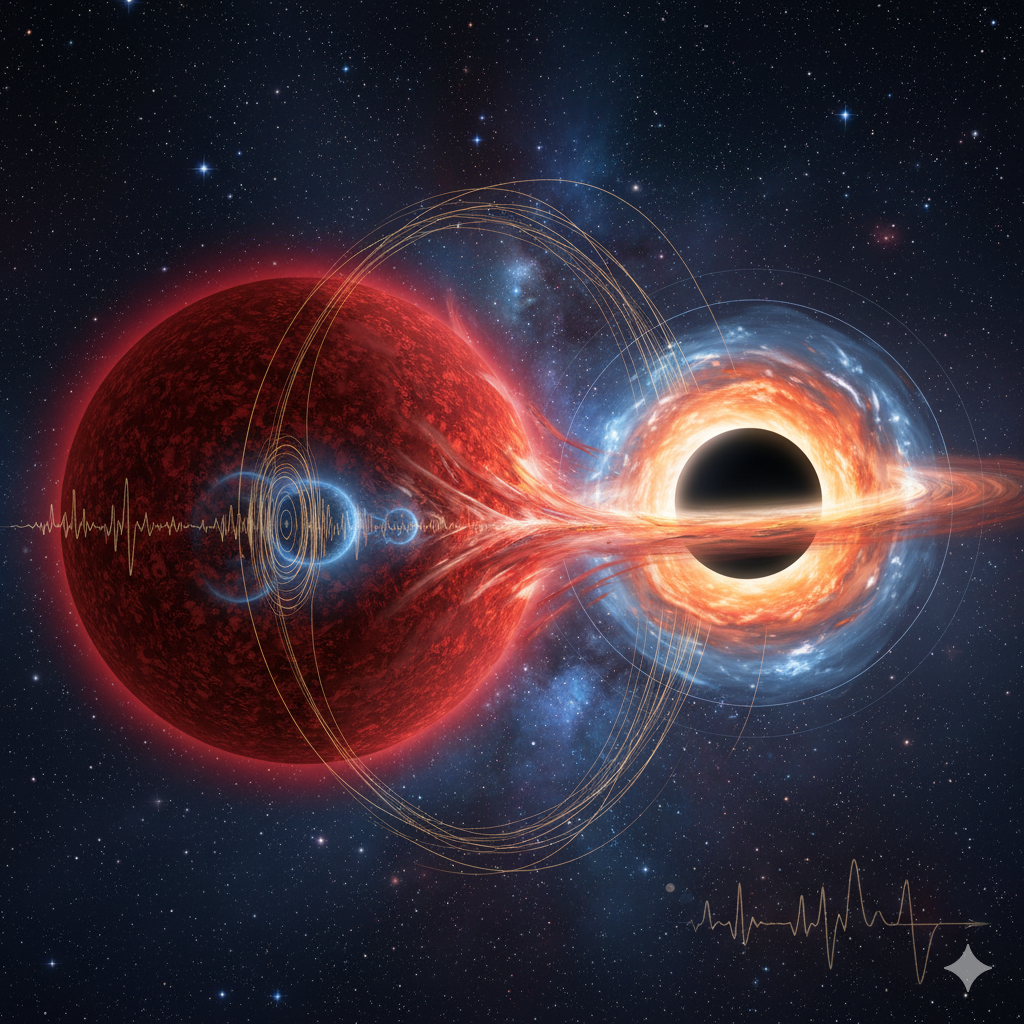

Red giant starquakes reshape what scientists think about quiet black holes

You live in a galaxy packed with black holes that never announce themselves. They do not blaze in X-rays or glow with stolen gas. They hide. Astronomers find them by watching the stars that dance around them.

Two such systems, called Gaia BH2 and…

Continue Reading