This photo of the Aurora Borealis storm was taken in Fairbanks, Alaska, Nov. 12. The

…

Category: 7. Science

-

‘Star of the Magi’ Program Highlights UW Planetarium Schedule During December

-

‘Star of the Magi’ Program Highlights UW Planetarium Schedule During December

This photo of the Aurora Borealis storm was taken in Fairbanks, Alaska, Nov. 12. The

…Continue Reading

-

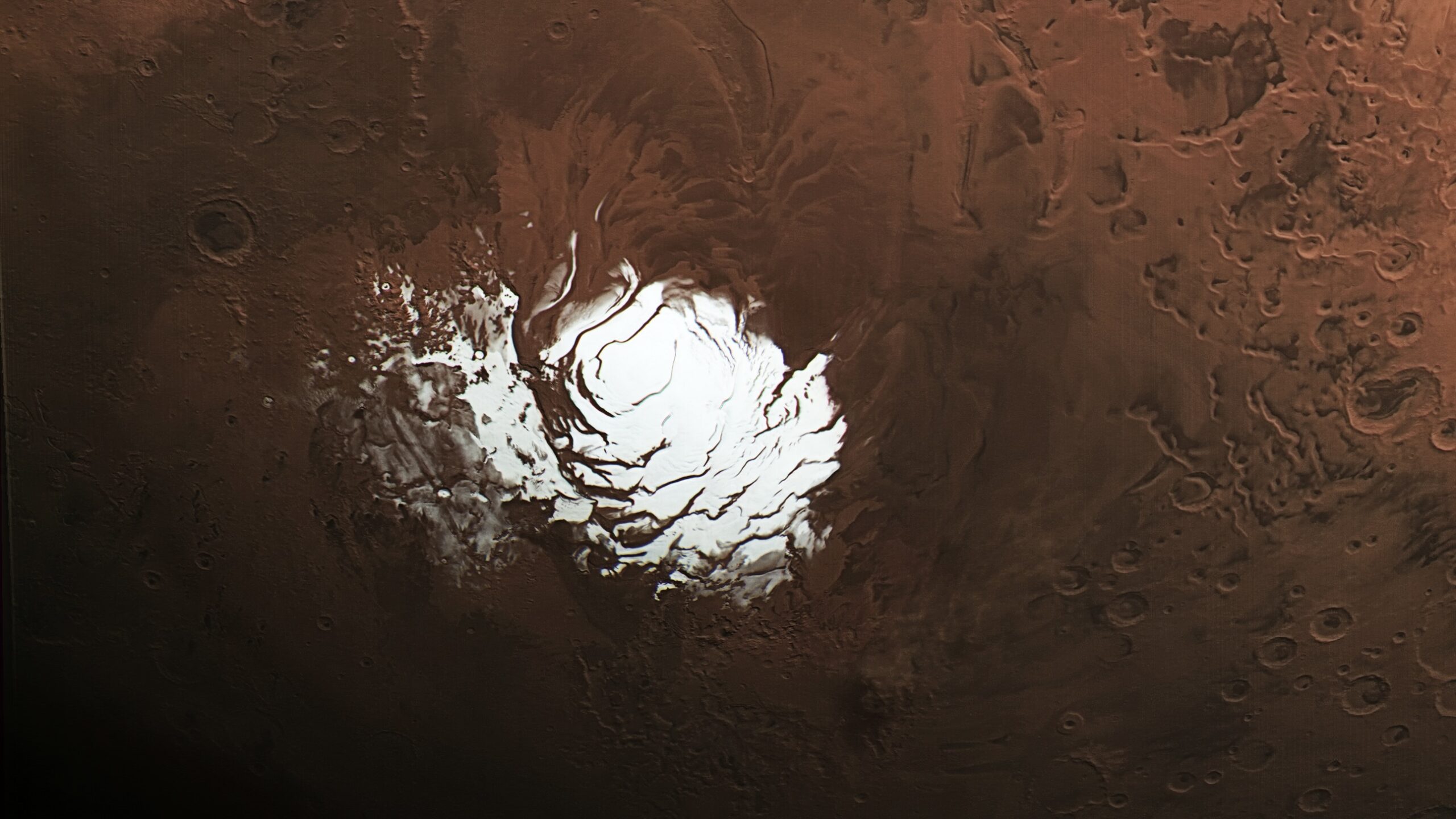

NASA Orbiter Shines New Light on Long-Running Martian Mystery

Results from an enhanced radar technique have demonstrated improvement to sub-surface observations of Mars.

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has revisited and raised new questions about a mysterious feature buried beneath thousands…

Continue Reading

-

Photographer captures eerie red halo hovering over the Italian Alps in rare ‘elve’ sighting (photo)

An “elve” lasts for less than a thousandth of a second. (Image credit: Valter Binotto) For a split second over northern Italy, the night sky erupted with a colossal glowing red ring. One photographer was in the right place at the right time.

Continue Reading

-

Purdue’s single-photon switch promises ‘terahertz-speed’ photonic computing…

25 Nov 2025

…and KAIST’s efficient quantum process tomography enables scalable optical quantum computing.

There are few technologies more fundamental to modern life than the ability to control light with precision. From fiber-optic…

Continue Reading

-

Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS May Be Headed For A Close Encounter Before It Heads Towards Gemini

A new pre-print paper suggests that our latest interstellar visitor, comet 3I/ATLAS, may be headed for one final close encounter before it departs our Solar System in 2026. The paper, which focuses on dynamical simulations of the object, also…

Continue Reading

-

Quantum Science Information | AZoQuantum.com

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…Continue Reading

-

Quantum Science Information | AZoQuantum.com

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…Continue Reading

-

Optics / Photonics Information | AZoOptics.com

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…Continue Reading

-

Optics / Photonics Information | AZoOptics.com

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…Continue Reading