Killing neighbours and taking over their lands led to a baby boom for a chimpanzee community in Uganda — potentially showing why it can be advantageous for chimps to start wars.

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) have long been known for violent…

Killing neighbours and taking over their lands led to a baby boom for a chimpanzee community in Uganda — potentially showing why it can be advantageous for chimps to start wars.

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) have long been known for violent…

Terms

While we only use edited and approved content for Azthena

answers, it may on occasions provide incorrect responses.

Please confirm any data provided with the related suppliers or

…

Humans have long wondered when and how we begin to form thoughts. Are we born with a pre-configured brain, or do thought patterns only begin to emerge in response to our sensory experiences of the world around us? Now, science is…

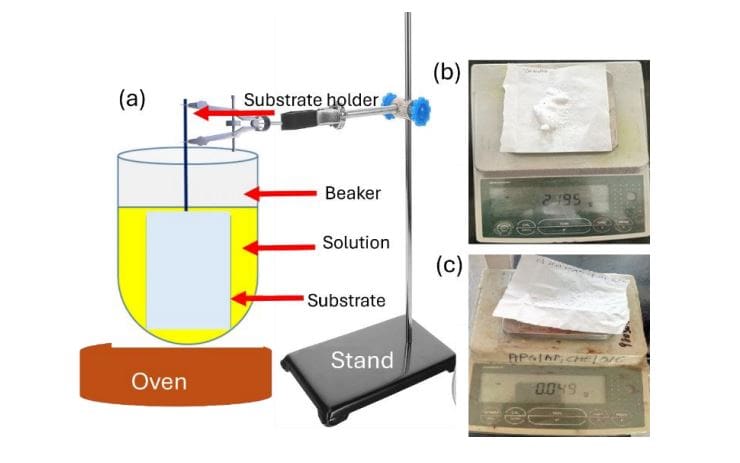

Manganese-doped zinc sulfide nanocrystalline thin films hold promise for next-generation optoelectronic and photovoltaic devices, and researchers are actively exploring methods to optimise their properties. Himal Pokhrel from The University of…

A new generation of stratospheric balloons and high-altitude uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) could soon connect the world’s unconnected with high-speed internet at a fraction of the prices commanded by operators of satellite megaconstellations…

24/11/2025

0 views

0 likes

A team of researchers at Stanford University, led by Manu Prakash, an associate professor of bioengineering who runs a “curiosity-driven” lab, has created the world’s first self-powered mechanical circuits that learn from the environment around…

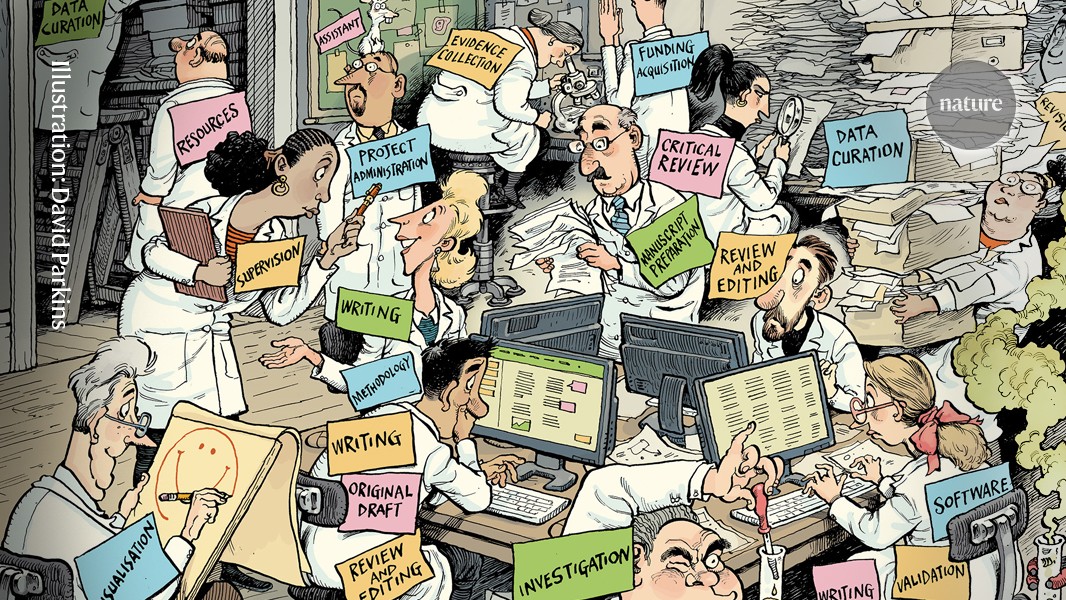

A decade ago, we and others launched a tool for clarifying the roles of each author of a research paper. The Contributor Role Taxonomy (CRediT) includes 14 types of contribution, from conceptualization to software and data curation. It was…

Ayalew, H. et al. Agro-ecological base differences of village-based local chicken performance and household product consumption in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 9 (1), 2164662 (2023).

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to