This little plant is a lot tougher than it looks.

Researchers exposed moss spores to the harsh environment of space for nine months recently, and the results were surprising, a new study reports.

This little plant is a lot tougher than it looks.

Researchers exposed moss spores to the harsh environment of space for nine months recently, and the results were surprising, a new study reports.

This week’s science news has been fraught with controversy, as the three former leaders of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) took to a webinar to describe the chaos unfolding at the agency since the start of the second…

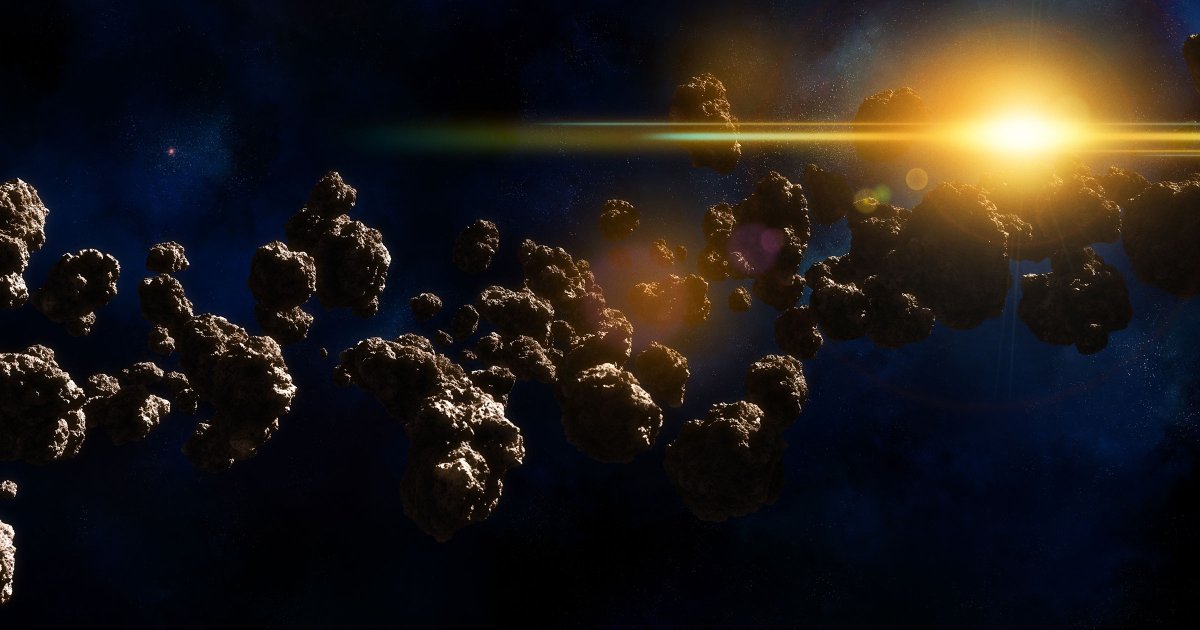

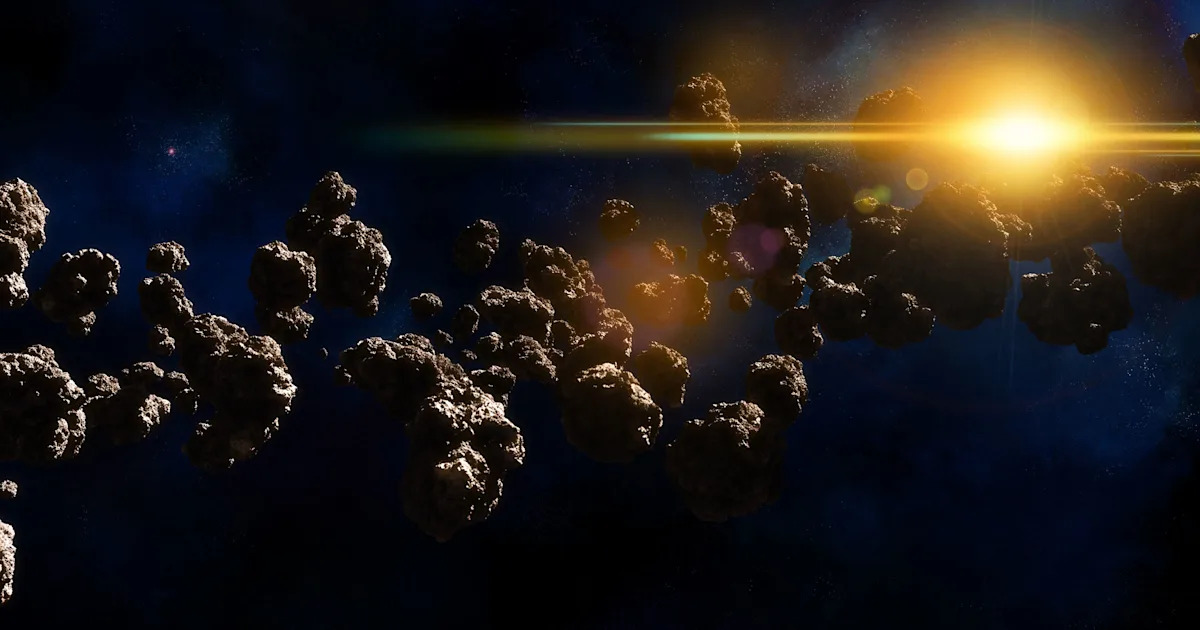

Astronomers have spotted an intriguing cluster of objects in the Kuiper belt, the enormous, donut-shaped region of icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune.

As New Scientist reports, it’s the second distant structure to have been observed…

Astronomers have spotted an intriguing cluster of objects in the Kuiper belt, the enormous, donut-shaped region of icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune.

As New Scientist reports, it’s the second distant structure to have been observed in the…

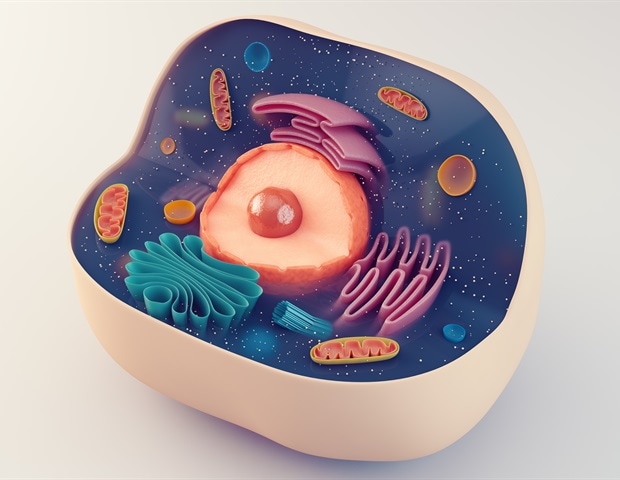

Biomedical researchers at Texas A&M University may have discovered a way to stop or even reverse the decline of cellular energy production – a finding that could have revolutionary effects across medicine.

Dr. Akhilesh K. Gaharwar…

Only two weeks after fertilization, the first sign of the formation of the 3 axes of the human body (head/tail, ventral/dorsal, and right/left) begins to appear. At this stage, known as gastrulation, a flat and featureless sheet of…

Kissing is an emotional expression of love when one feels extremely close to the other person due to passionate emotions. Researchers are of the view that such behaviours have deep biological roots and are not a result of any cultural invention.

…

Dear RW readers, can you spare $25?

The week at Retraction Watch featured:

Did you know that Retraction Watch and the Retraction Watch Database are projects of The Center of Scientific Integrity? Others include the