- Sinking Salted Ice Could Power Undersea Life on Europa extremetech.com

- Study suggests pathway for life in Europa’s ocean WSU Insider

- This Spider-Like Pattern on Europa Could Reveal Secrets Beneath Its Icy Shell Indian Defence Review

- Study…

Category: 7. Science

-

Sinking Salted Ice Could Power Undersea Life on Europa – extremetech.com

-

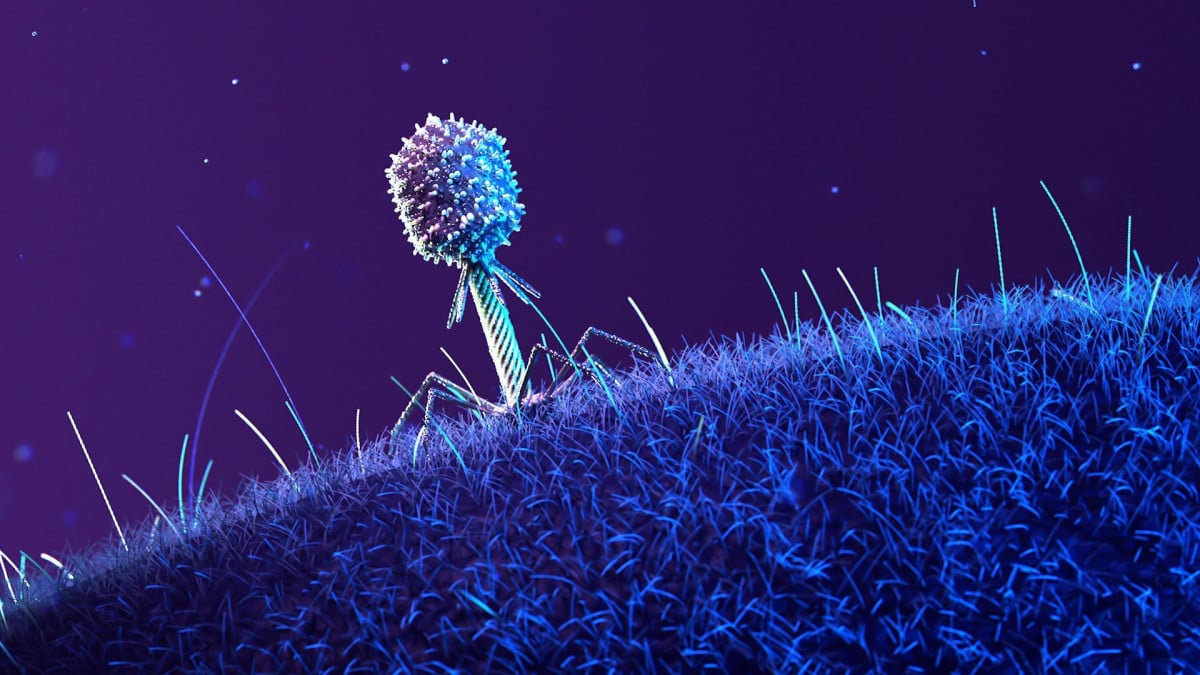

Mutations from Space Might Solve an Antibiotic Crisis

If humans are ever going to expand into space itself, it will have to be for a reason. Optimists think that reason is simply due to our love of exploration itself. But in history, it is more often a profit motive that has led humans to…

Continue Reading

-

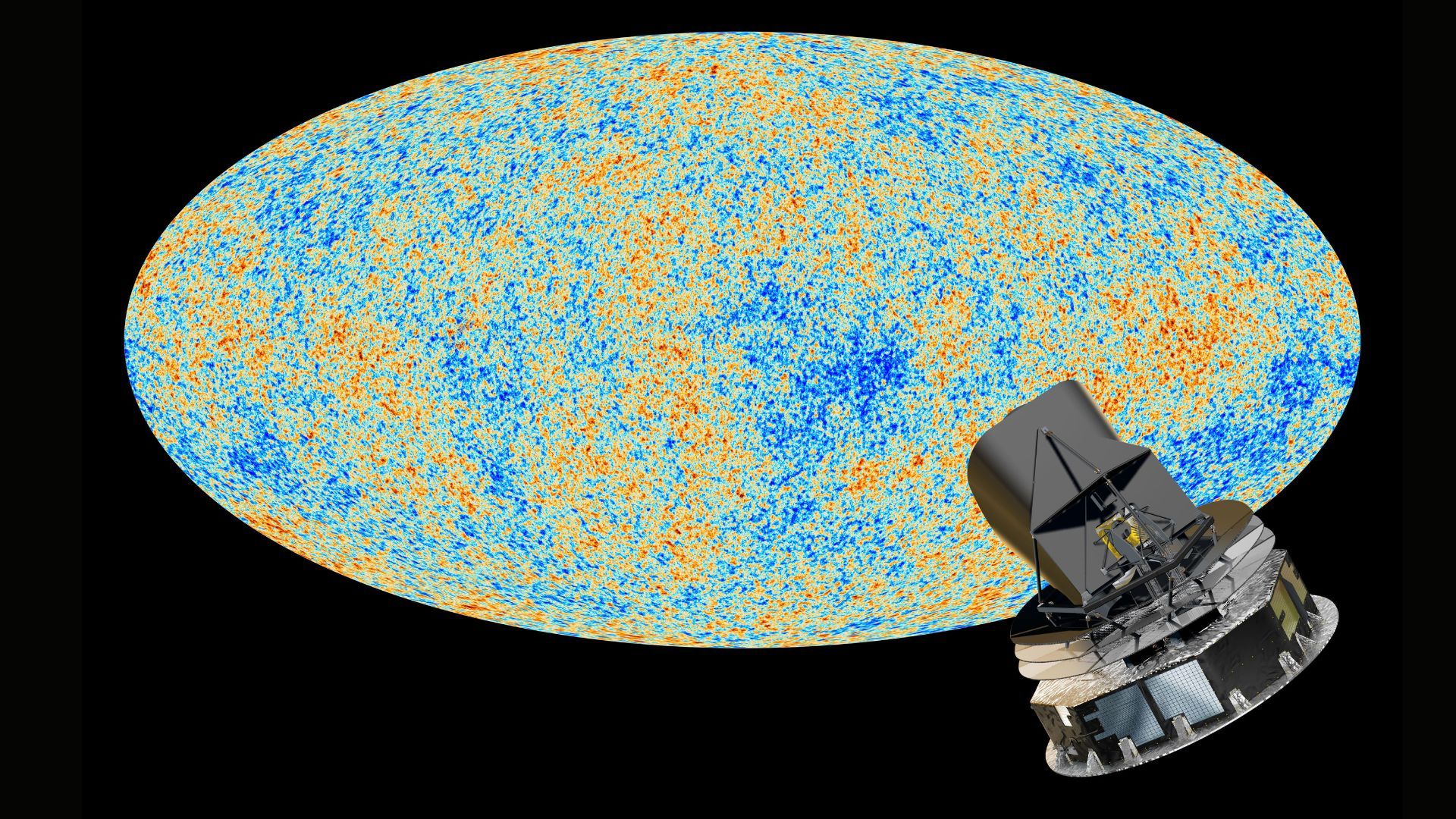

Scientists may be approaching a ‘fundamental breakthrough in cosmology and particle physics’, if dark matter and ‘ghost particles’ can interact

Two of the universe’s most mysterious particles may be colliding invisibly throughout the cosmos — a discovery that could solve one of the biggest lingering problems in our standard model of cosmology.

Those two elusive components — dark…

Continue Reading

-

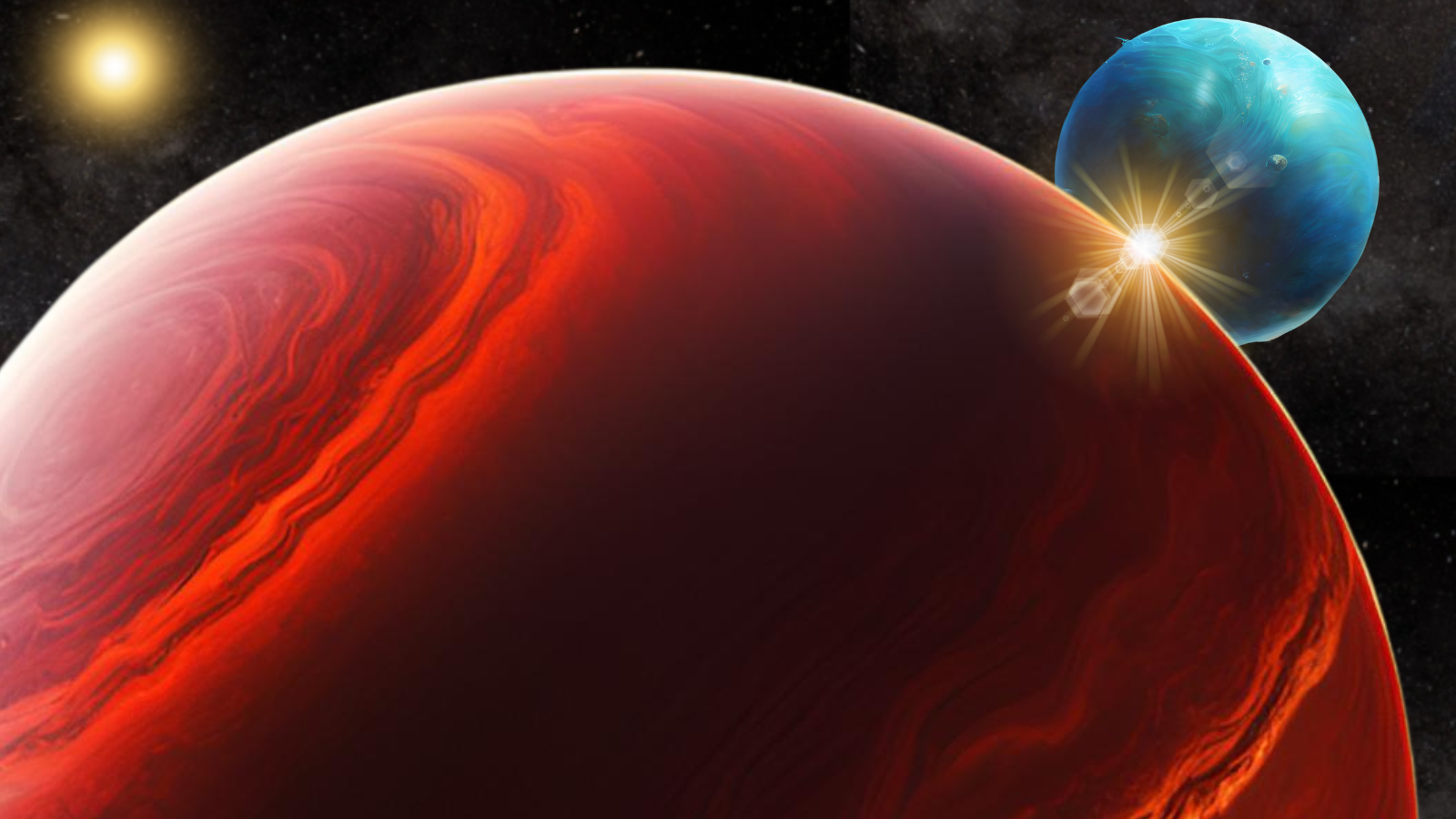

Wobbling exoplanet hints at a hidden exomoon so massive it could redefine the word ‘moon’ altogether

A gas giant planet beyond the solar that wobbles as it circles its star, hinting to astronomers that it is orbited by its own moon. To make this suspected discovery even more remarkable, if this moon exists it would be absolutely massive,…

Continue Reading

-

‘Periodic table’ for highly charged ions could advance atomic clocks

A new chart for highly charged ions (HCIs) has been proposed, aiming to replicate the conventional periodic table’s accessibility and patterns for the cutting edge of atomic physics. This table could help physicists that are looking to…

Continue Reading

-

Immigrant Whales Share Bubble Netting Techniques

New research from the University of St Andrews has found that the social spread of group bubble-net feeding amongst humpback whales is crucial to the success of the population’s ongoing recovery.

Bubble-net feeding is when a…

Continue Reading

-

Maynooth black hole research ‘unlocks one of astronomy’s big puzzles’

Researchers at Maynooth University have been exploring one of nature’s and astronomy’s major conundrums and they are much closer to the answer.

A team of researchers at Maynooth University (MU) have been…

Continue Reading

-

AI Breakthrough Transforms Enzyme Design

Enzymes with specific functions are becoming increasingly important in industry, medicine and environmental protection. For example, they make it possible to synthesise chemicals in a more environmentally friendly way, produce active…

Continue Reading

-

Physicists challenge a 200-year-old law of thermodynamics at the atomic scale

Two physicists at the University of Stuttgart have demonstrated that the Carnot principle, a foundational rule of thermodynamics, does not fully apply at the atomic scale when particles are physically linked (so-called correlated objects). Their…

Continue Reading

-

After 11 years of research, scientists unlock a new weakness in deadly fungi

Fungal infections claim millions of lives every year, yet treatment options have failed to keep pace with the growing danger. Scientists at McMaster University now report a discovery that could shift that balance. They have identified a molecule…

Continue Reading