You don’t have permission to access “http://www.spglobal.com/energy/en/news-research/latest-news/crude-oil/010926-oil-executives-make-diverging-pledges-to-trump-on-venezuelan-investment” on this server.

Reference…

You don’t have permission to access “http://www.spglobal.com/energy/en/news-research/latest-news/crude-oil/010926-oil-executives-make-diverging-pledges-to-trump-on-venezuelan-investment” on this server.

Reference…

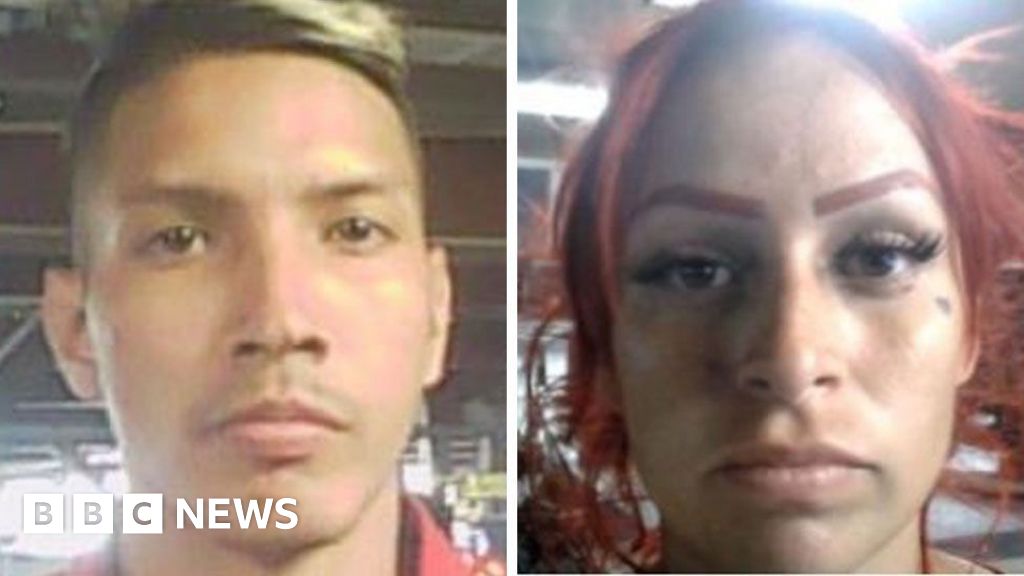

A man and woman who were shot by an immigration agent in Portland, Oregon, on Thursday had ties to the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, officials said.

In a news conference on Friday, Portland Police Chief Bob Day confirmed that both “do have some…

The Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who shot and killed 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis on Wednesday was dragged by a car in the line of duty last summer, according to court records.

Federal officials have not publicly…

Authorities have issued evacuation orders for people in Victoria’s Otways region as two fires burn out of control in the Great Otway National Park in the state’s south-west .

One emergency-level fire is burning on Cape Otway, west of Apollo Bay,…

Zahra Fatima & Cachella Smithand

Chris Fawkes,Lead weather presenter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK is bracing for widespread ice and freezing…

These are the key developments from day 1,416 of Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Published On 10 Jan 2026

Here is where things stand on Saturday, January 10:

US President Donald Trump is calling on oil executives to rush back into Venezuela as the White House looks to quickly secure $US100 billion ($149 billion) in investments to revive the country’s ability to fully tap into its expansive reserves of…

On Friday DHS identified the wounded driver as Luis David Nino-Moncada, who it said entered the US without documentation in 2022 and has since been arrested for allegedly driving under the influence (DUI) and unauthorised use of a vehicle.

The…

Fire crews are bracing for an increase in bush and grass fires, as conditions are set to worsen by Saturday afternoon.

As of 12pm (AEDT), there were 46 fires burning across New South Wales, with about six yet to be contained.

NSW Rural Fire…

A Palestinian academic has failed in his latest attempt to be reunited with his family in the UK after the Home Office concluded their case was not urgent and it was more appropriate for his two children to remain with their mother in a tent in…