KYIV, Ukraine — A Russian missile strike on port infrastructure in Odesa in southern Ukraine killed eight people and wounded 27, Ukraine’s emergency service said Saturday, as a Kremlin envoy was set to travel to Florida for talks on a

Category: 2. World

-

Winter solstice 2025: What to know about the shortest day of the year

FILE – Revellers celebrate the pagan festival of ‘Winter Solstice’ at Stonehenge in Wiltshire in southern England on December 22, 2023. (Photo by BEN STANSALL/AFP via Getty Images)

The winter solstice is almost here to mark the…

Continue Reading

-

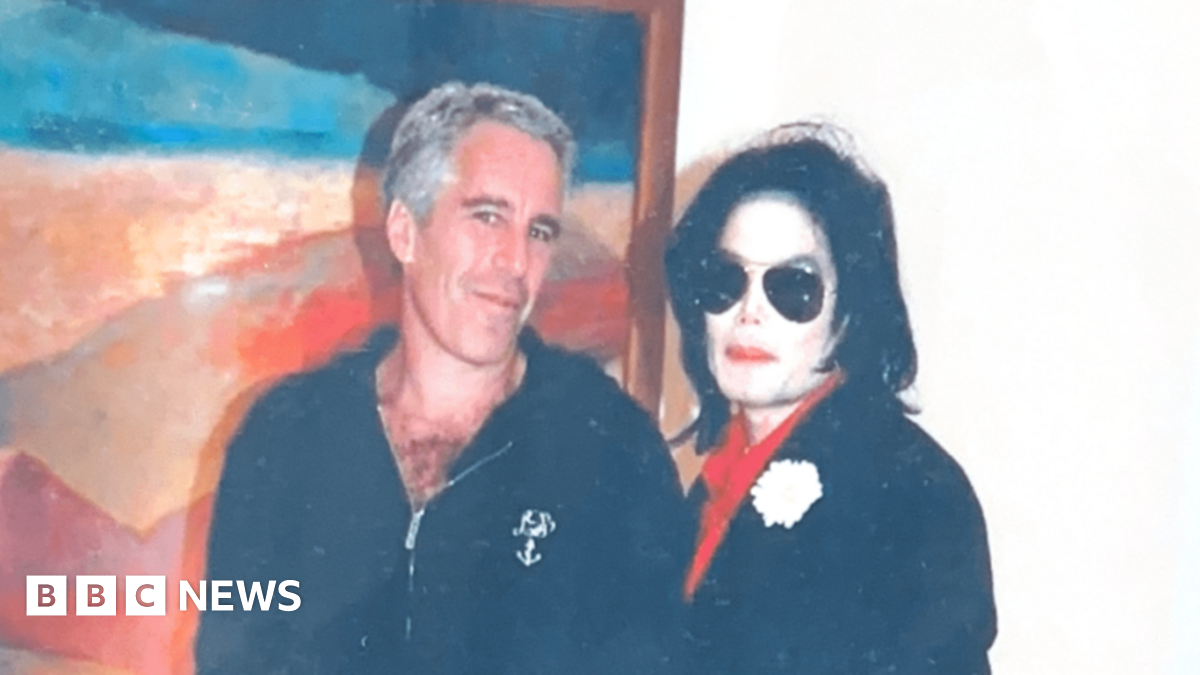

Live updates: Epstein files released with heavy redactions as thousands more documents expected

This isn’t the first time Pam Bondi has faced controversy over document handlingpublished at 11:18 GMT

Image source, ReutersAttorney General Pam Bondi is facing criticism for releasing only about 1% of the full volume of the…

Continue Reading

-

Israeli troops kill six Palestinians sheltering in Gaza school, say hospital chiefs | Gaza

The Israeli military killed six Palestinians, including a baby, who were in a school that sheltered displaced people in Gaza City on Friday, hospital officials have said. The attack brings the number of Palestinians killed by Israel to 401 since…

Continue Reading

-

Bangladesh holds state funeral for slain youth leader amid tight security

Item 1 of 4 Supporters block the Shahbagh Square as they protest, demanding justice for the death of Sharif Osman Hadi, a student leader who had been undergoing treatment in Singapore after being shot in the head, in Dhaka, Bangladesh December…

Continue Reading

-

Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus M.Ryzhenkov meets management of National Museum of Oman – Министерство иностранных дел Республики Беларусь

- Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus M.Ryzhenkov meets management of National Museum of Oman Министерство иностранных дел Республики Беларусь

- Belarus Proposes Strategic Tourism Cluster In Oman To…

Continue Reading

-

Remembering the lives lost to a senseless act of terror : NPR

Mourners gather around floral tributes at Bondi Pavilion to honor the victims of the Bondi Beach shooting in Sydney on…

Continue Reading

-

As officials uncover more information about the Brown and MIT professor shooting suspect, key questions remain

Police lights flashed for hours as law enforcement officers surrounded a storage facility in Salem, New Hampshire, Thursday night, finally closing in on a suspect who unleashed deadly attacks on two communities…

Continue Reading

-

‘We must tell children why families left Alderney during WW2’

More than 350 saplings have been planted to create the woodland to mark Homecoming Day on 15 December.

Claudie said her son was inquisitive and the “right age” for her to start explaining what happened to their family and why everyone left the…

Continue Reading

-

Bangladesh holds state funeral for slain youth leader amid tight security – Dawn

- Bangladesh holds state funeral for slain youth leader amid tight security Dawn

- Protests escalate in Bangladesh after death of student leader Hadi Al Jazeera

- Bangladesh newspaper staff recall ‘gasping for air’ as offices set ablaze BBC

Continue Reading