Klinefelter syndrome is the most common genetic cause of azoospermia. Owing to limited awareness and phenotype variability, the disease has been historically diagnosed in men during mid-adulthood during workup for fertility issues. However, advances in prenatal testing and screening have altered the diagnostic paradigm, raising questions about whether surgical sperm retrieval should occur in adolescence or be delayed until a desired time in adulthood.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This was the basis for a new study led by Scott Lundy, MD, PhD, and colleagues, who conducted a meta-analysis to assess the relationship between age and the rate of retrieval in sperm extraction in patients with nonmosaic (47, XXY) Klinefelter syndrome. They published their findings in the prestigious journal, Fertility and Sterility.

Patients with Klinefelter syndrome are likely to experience germ cell apoptosis, seminiferous tubular hyalinization and testicular interstitial hyperplasia at puberty, which complicates the perceived window for intervention and has, historically, created urgency around sperm retrieval around the time of puberty.

“We don’t know why, but if there are no germ cells or sperm precursors, then there can’t be any sperm down the road. Some providers advocate for testicular sperm extraction surgery on children soon after puberty to freeze it for future fertility treatment, like in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection,” explains Dr. Lundy, adding, “This has been somewhat controversial in our field.”

This approach raises several ethical concerns, including potentially unnecessary surgery in children, who may not fully understand its implications or ultimately want to have children. Further, it does not guarantee a successful outcome, and there is a psychological cost associated with knowledge of likely infertility so early in life.

A closer look at the study

“We wanted to understand this to guide patients and parents to a more nuanced degree,” says Dr. Lundy. A previous meta-analysis was conducted in 2017 but did not include retrieval rates for adolescents.

Using PubMed, Embase and Medline, the research team extracted data from 48 studies, with a total of 2,815 participants. The researchers included outcomes from both conventional sperm extraction methods and microdissection, the current standard of care, in those with nonmosaic Klinefelter syndrome. In addition to age and sperm retrieval rate, they analyzed live birth rate, total testicular volume, preprocedural testosterone, and blood follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels.

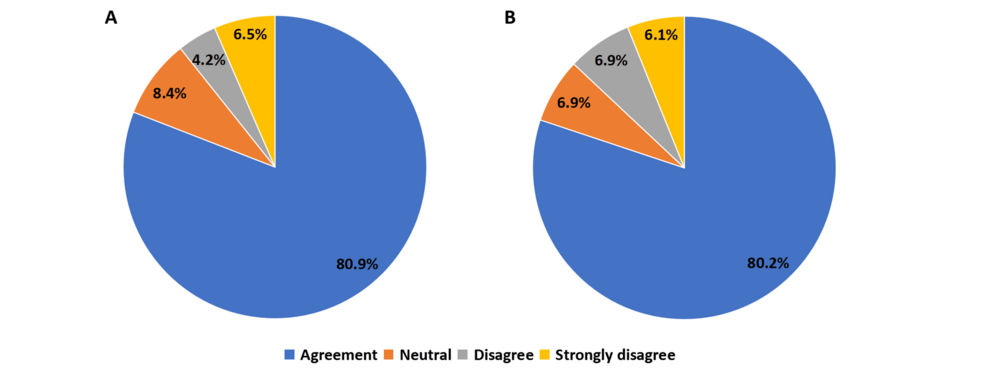

Of the 48 studies, researchers found a median sperm retrieval rate of 44%. In total, 24 studies found groups of patients with positive sperm retrieval compared to negative sperm retrieval. Ages of the positive sperm retrieval cohorts were, on average, 2.8 years younger than those with negative sperm retrieval (95% confidence interval: − 3.62 to − 2.02 years; I2 = 78%). The researchers also reported no difference in sperm retrieval rates between the adolescent and adult groups (45% vs. 42%) across all studies.

The authors also reported a nonsignificant quadratic relationship between age and sperm retrieval rates, suggesting that rates may decline after age 40.

No meaningful difference in sperm retrieval rates

The takeaway, Dr. Lundy emphasizes, is that there’s no meaningful difference in the surgery’s success rate when performed in puberty versus at the average age for desired family planning, which tends to be around 30. “We can now provide some reassurance when counseling parents and patients alike that there is no urgency to rush into surgery.”

Although he cautions, one of the studies indicates that sperm retrieval may become less successful in this patient population around 40, which is just another data point for consideration when counseling patients with Klinefelter syndrome.

Questions that remain

Still, questions involving testosterone therapy in pediatric patients remain. In some cases, Dr. Lundy says it’s “certainly necessary” to facilitate puberty in patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome. In others with lower-to-normal levels of testosterone, it could negatively affect testicular function and sperm production.

“There is a possibility that pediatric patients who have gone through puberty and are placed on testosterone might have a better fertility outcome if they weren’t on testosterone. We need more data to guide which patients receive testosterone and which ones don’t,” he cautions.